| |

|

|

|

| |

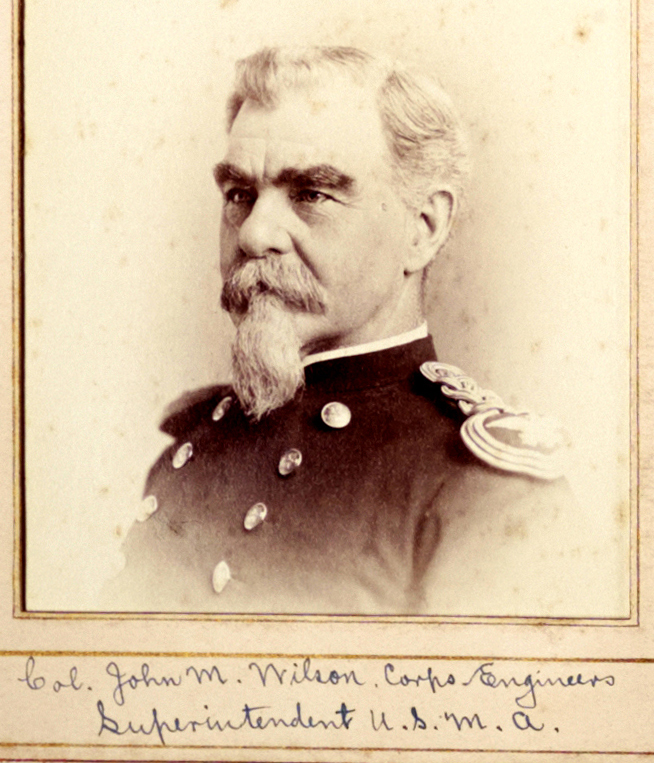

Brig. Gen. John M. Wilson as a colonel.

USMA Archives |

|

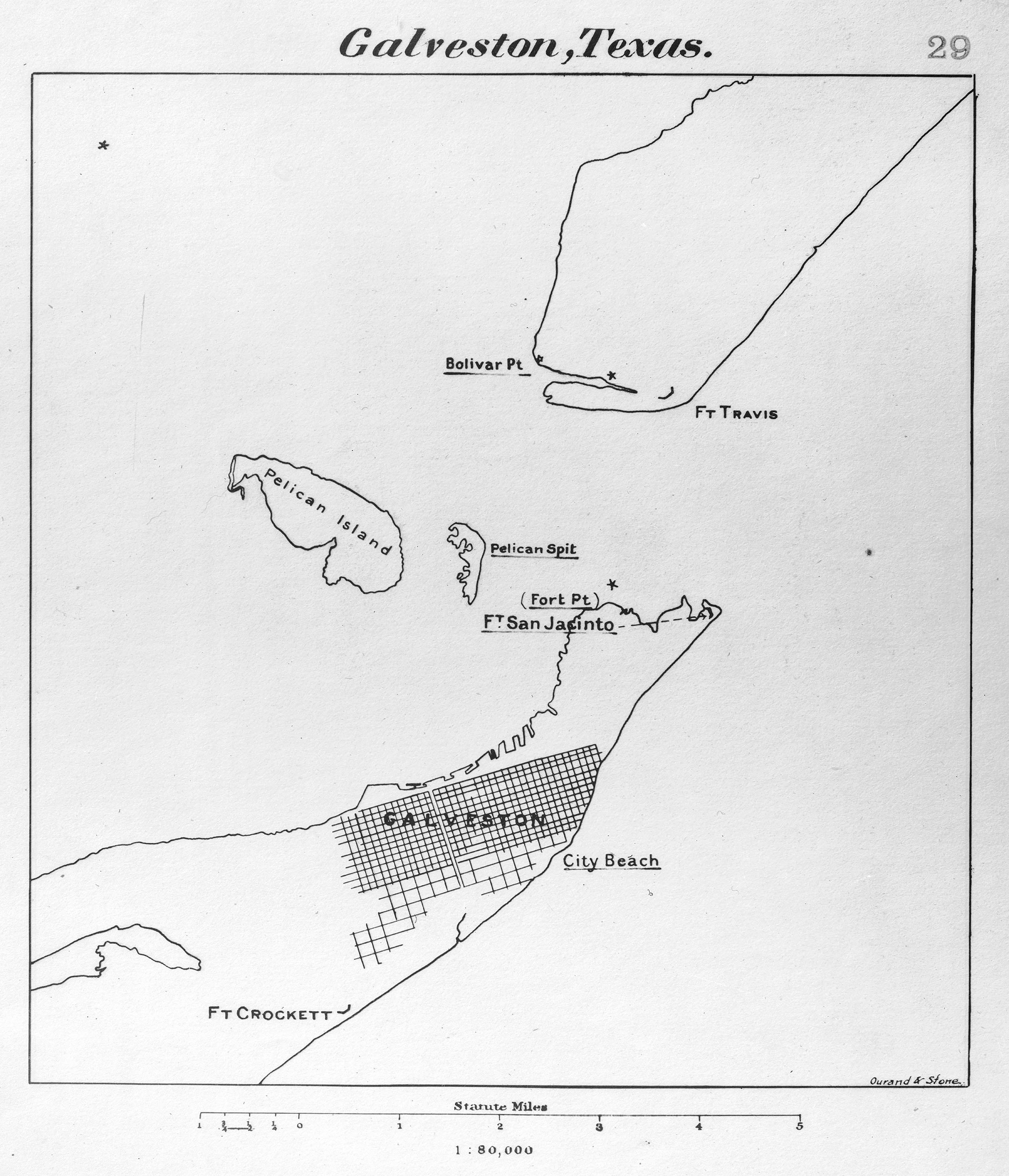

Map of Coast Defenses at

Galveston, Texas, no date.

National Archives, 175739417 |

A Western Union telegram arrived at the offices of the Army Corps of Engineers in Galveston, Texas, on April 23, 1898, two days before the formal U.S. declaration of war against Spain. It came from the chief of engineers, Brig. Gen. John Moulder Wilson, and read simply, “Plant your mines.” The Spanish–American War—later dubbed the “splendid little war”—raged for a mere ten weeks yet ushered in both the destruction of a centuries-old Spanish empire in America and the rapid elevation of the United States as a major world power with territorial claims extending into the Caribbean and across the Pacific. Recognized mainly as a naval conflict that pitted a modern U.S. fleet against an aged Spanish armada, the war also saw the U.S. Army play a prominent role, particularly in Cuba where Teddy Roosevelt and his Rough Riders rode to fame at the Battle of Kettle Hill and the Siege of Santiago. Throughout those engagements and later in the Philippines, U.S. Amy Engineers provided combat support by erecting landing piers, constructing bridges, building and maintaining roads, repairing and operating railroads, and, at multiple port cities along the Atlantic and Gulf Coasts, by placing heavy guns and laying mines. A recently rediscovered cache of records from the Galveston District sheds light on its hurried and valiant efforts to defend its namesake port city against any Spanish threat.

On February 15, 1898, the USS Maine, a U.S. Navy warship, exploded in Havana Harbor. Many American journalists considered the incident an act of aggression on the part of Spain and clamored for war. These events touched off a flurry of correspondence between Wilson, the chief of engineers in Washington, and a young engineer lieutenant named Charles S. Riché in Galveston. Wilson was a West Point graduate, class of 1860, and a recipient of the Medal of Honor for his actions in the Civil War at Malvern Hill. After the war, he enjoyed a long and successful career with the Corps of Engineers, serving in various capacities in the Great Lakes region and later in Washington, where he headed the Office of Public Buildings and Grounds during both Grover Cleveland administrations. He served as superintendent of West Point from 1889 to 1893 and as Northeast Division commander before returning to Washington as chief of engineers in 1897. September of that same year saw Riché take command of the engineer office at Galveston. He, too, was a graduate of the Military Academy, ranking third in the class of 1886.

Galveston was by the 1890s a booming commercial hub with a population of 37,000. By virtue of its natural harbor, it was the center of trade in Texas and one of the largest cotton ports in the nation, in competition with New Orleans. Congressional action in 1897 directed the secretary of war to make an examination and survey for a water channel of not less than 25 feet deep through Galveston Bay and Buffalo Bayou to Houston. Following the successful survey, the actual work creating the channel would fall to the Galveston engineer office, but rising tensions with Spain pushed those efforts aside for a time. In a letter dated February 26, 1898, General Wilson tasked Lieutenant Riché with quietly preparing the defenses of Galveston harbor “in the event of sudden war.” These measures would ultimately include the use of mines, torpedoes, and heavy guns. The chief of engineers sent seven enlisted men—one noncommissioned officer and six privates—from the Engineer School of Application at Willets Point, New York, to assist. Along with them came engineer officer, Lt. Harry Burgess, a West Point graduate of 1895 assigned to the defense of the harbor at Galveston. He had just completed the torpedo course at the Engineer School, and he and Riché worked in tandem to address the emergency defense needs of Galveston and the vicinity.

Plans firmed up over the next few weeks. In a letter to Riché dated March 18, Wilson ordered the immediate construction of “two emplacements for ten-inch guns on disappearing carriages…at City Beach, and two emplacements for 8-inch guns on disappearing carriages…at Bolivar Point.” These two locations straddled the entrance to Galveston Bay through the barrier islands. With the prospect of war on the horizon, Wilson emphasized the critical nature of the work and reputational risk for the Corps of Engineers: “The operations of the Engineer Department…will be viewed by the entire country, and your own reputation and that of the Corps of Engineers is involved in the matter.”

|

|

|

|

Two views of Fort San Jacinto in fall of 1902, following the war and the devastating hurricane at Galveston.

National Archives, 278145 (left) and 278147 (right)

|

Two weeks later, on April 3, Wilson wrote to Riché again, this time reporting that he had ordered additional torpedoes while acknowledging that “it will probably take three months to obtain what will be needed for one fourth of our coastline.” Fretting about the maddening but unavoidable delays, Wilson advised his junior grade officer:

It is not the fault of the Corps of Engineers that we are not fully prepared, but it will be its fault and that of each district officer in case we do not at once take advantage of this limited means now at our command…. Use every effort in this emergency.

By the second week of April, Riché and Burgess were reporting progress. The gun placements were well into construction, but, unbeknownst to them, it would be October before the first of the disappearing carriages would arrive, long after the immediate threat had passed. The mining of the harbor was much further along. Wilson’s clear guidance on the latter had been communicated in a letter dated April 19: “complete every detail of the mining defense of the harbors under your charge, so far as materials will admit, except placing the mines in position, and that upon receipt of a telegram from me to ‘go ahead with the mines,’ you will place the mines in position and complete everything necessary for operating them, as rapidly as possible.”

That order came just four days later in the form of two Western Union telegrams. The first directed Riché to “Plant your mines.” The second authorized the lieutenant to “go ahead and place them when you deem best leaving one channel to be finally completed.” He and Burgess complied and, later that day, the Galveston Tribune ran with a headline, “Warning on Mines,” advising “vessel owners, masters and pilots…that submarine mines have been planted in the entrance to Galveston harbor and in the Gulf of Mexico in front and Westward of the City of Galveston.” It further advised that “no vessel should attempt to cross this area at night, no vessel should anchor in this area, and no vessel should cross this area at any but very slow speed.” For the next several months, personnel of the Galveston engineer office patrolled the harbor daily, testing the mines, repairing defects, keeping batteries and operating devices in order, and holding the system ready for immediate service. In July 1898 the engineers added search light facilities to the harbor defenses. Meanwhile, the work of driving piles and pouring concrete continued at the battery sites in absence of either carriages or guns.

The wartime threat to Galveston had largely abated by late June. Riché had by then been reassigned to New Orleans and the First U.S. Volunteer Infantry. His replacement was the more senior Maj. James B. Quinn who had served at the Galveston engineer office in the 1870s. It fell on Quinn to suspend night work and return his construction crews to eight-hour days. The war ended on August 13, and the following month Quinn oversaw the removal of mines from Galveston Harbor. Also in September, he received word from the Ordnance Department that the “Watertown Arsenal [Massachusetts] has this day been directed to issue to you 10-inch Disappearing Carriage ARF Model 1896.” By late October, though, only the 8-inch gun carriages had been received and uploaded at Bolivar Point. A report dated January 25, 1899, mentioned that all of the guns—both the 10-inch and 8-inch batteries—were in place and fully functional. These two batteries later formed the nucleus of two major installations that safeguarded Galveston Island and its harbor for the next fifty years. These were Fort San Jacinto (at City Beach) and Fort Travis (at Bolivar Point).

Brigadier General Wilson retired from the Corps of Engineers in 1901. He served as president of the Columbia Hospital for Women from 1902 to 1907 and was afterwards active for many years in the cultural life of Washington, D.C. He died in February 1919. Lieutenant Riché returned to the Galveston engineer office in November 1898 and remained there for more than four years. If his first stint had been defined by the Spanish–American War, his second was punctuated by a crippling hurricane that swept across Galveston in 1900, decimating the island, destroying Fort San Jacinto, and killing thousands of people. It still ranks among the deadliest natural disasters in U.S. history. His unprecedented third rotation, this time as Galveston District commander from 1912 to 1916, was somewhat less eventful, but he did have the satisfaction of overseeing the opening of the deep-water Houston Ship Channel. Through its successful defense of Galveston at the outbreak of war and its work after the Great Hurricane to protect the region from devastating storm surge, the Corps of Engineers ushered in a period of rapid growth and development that ultimately saw Houston eclipse Galveston as the primary commercial center in Texas and its largest port.

-1.jpg?ver=Kp3CB7Q841JASMhqjnlnKA%3d%3d) |

|

-2.jpg?ver=Kp3CB7Q841JASMhqjnlnKA%3d%3d) |

Images of Wilson's telegrams to Riché in 1898.

Office of History, Galveston District Collection, Bx 12, Fd 1 |

| * For more information on the history of Galveston District, see Custodians of the Coast. * |

***

May 2023. No. 162.