III. "Through Flood, Mud, Snow, and Forest"—Sustaining Field Parties during the Wheeler Survey

| |

|

| |

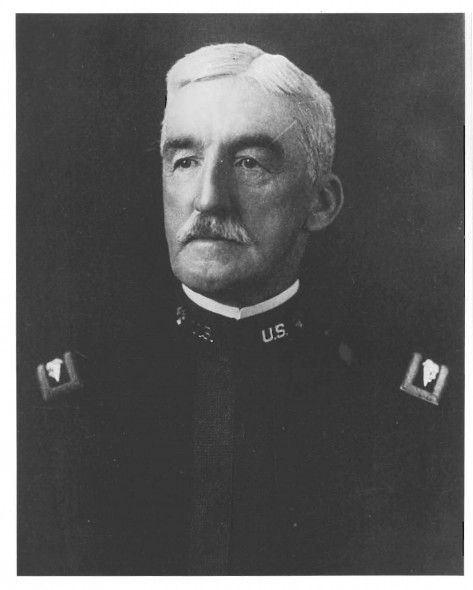

Rogers Birnie

National Geographic Society

|

On October 3, 1875, Lt. Rogers Birnie, Jr., his survey party, and their mules arrived at Camp Independence, a U.S. Army station in eastern California’s Owens Valley. The group had spent most of the last month surveying Death Valley, a daunting task given the intense heat of the desert in late summer. At one point, the mules had no fresh water for 48 hours, and one mule died from exhaustion. Now in camp, the party was able to replenish their rations and allow their mules to recuperate.

Birnie’s crew was part of the Wheeler Survey, a multi-year scientific, economic, and mapping expedition of the American West under Lt. George M. Wheeler of the Corps of Engineers. To cover as much area as possible during the more temperate summer and fall working seasons, Wheeler divided his personnel into field parties of six to ten men, both military and civilian. Critically, these parties needed supplies and equipment to complete their work in difficult terrain and remote environments. The logistics experience of the military cadre provided a key advantage in planning and executing successful surveys.

Staffing

Wheeler hired twelve individuals over the course of the survey (1871-79) to perform administrative tasks as clerks and general assistants. Their duties included copying Wheeler’s official letters and orders into a register, handling money, and managing property. Most of the administrators worked in the survey’s headquarters in Washington, D.C., but a few worked alongside Wheeler in the field. Isaiah Brown, one of the few identified African American employees, acted as Wheeler’s messenger from 1876 to 1879.

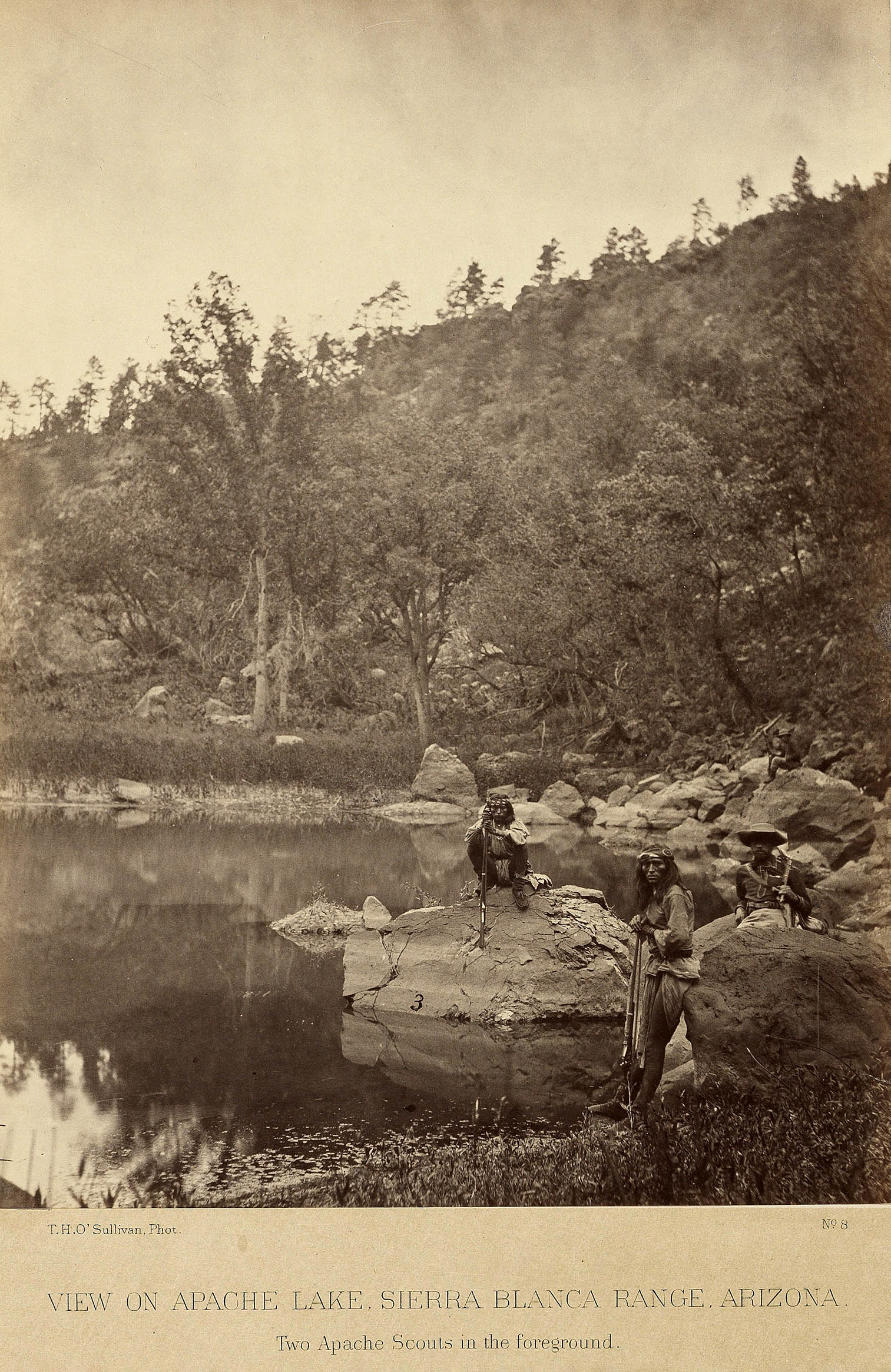

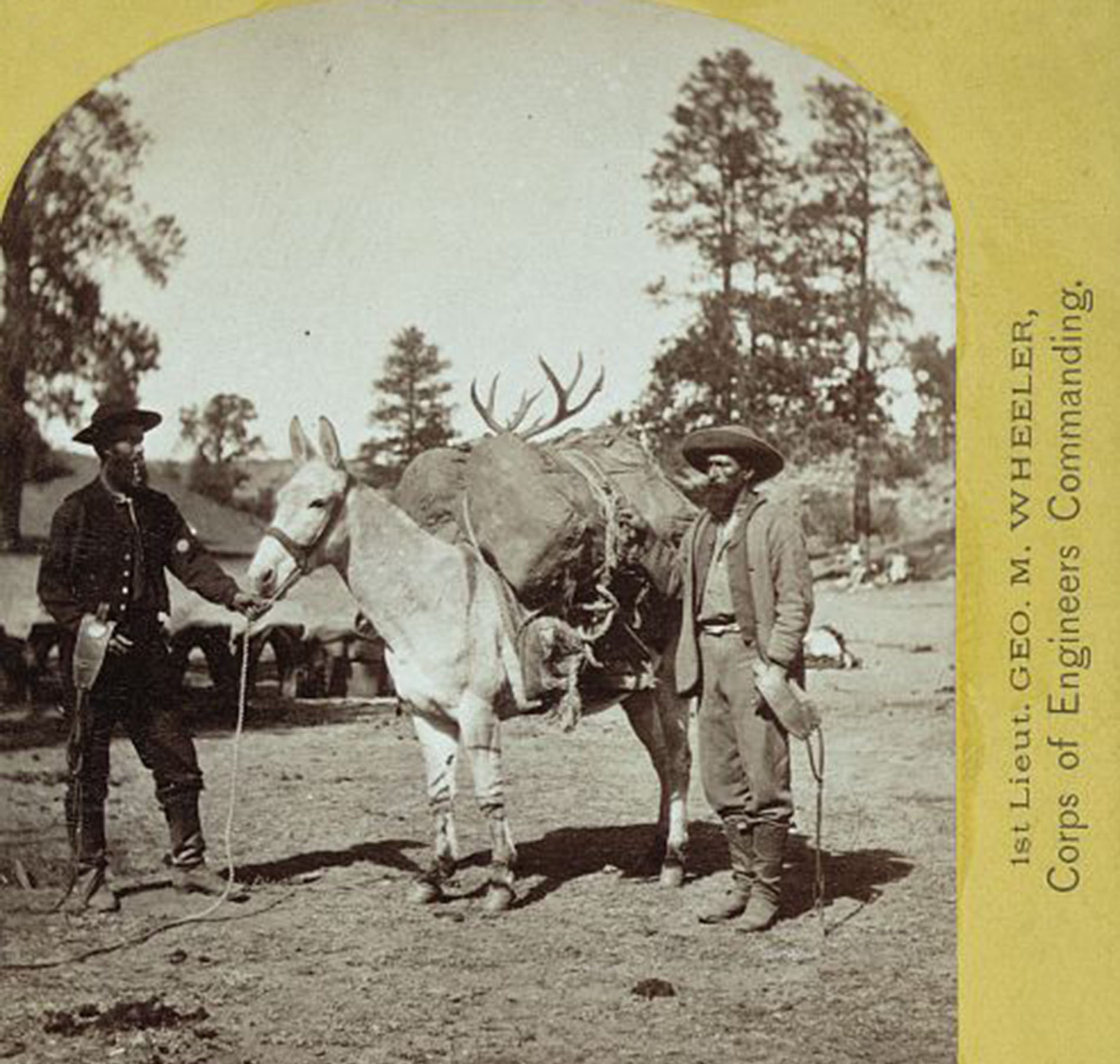

An Army lieutenant, usually a recent West Point graduate, led the typical Wheeler Survey field party. Attached to each team were one principal and one assistant topographer, an odometer reader, a meteorologist, and possibly a scientist or two. A contingent of manual laborers aided parties in the field. Herders handled the mules and horses, while teamsters drove the wagons. Packers and porters managed the survey members’ general and scientific equipment. Cooks prepared the meals. Finally, the survey hired both frontiersman and Native American guides during its first few years to help teams navigate dangerous areas like Death Valley and the Colorado River.

|

|

|

|

A typical western survey party of the 1870s.

U.S. Geological Survey,

|

Photo by official survey photographer Timothy O’Sullivan capturing images of two Native American Apache scouts. Office of History |

Wheeler survey members with pack and the all-important mule. Library of Congress

|

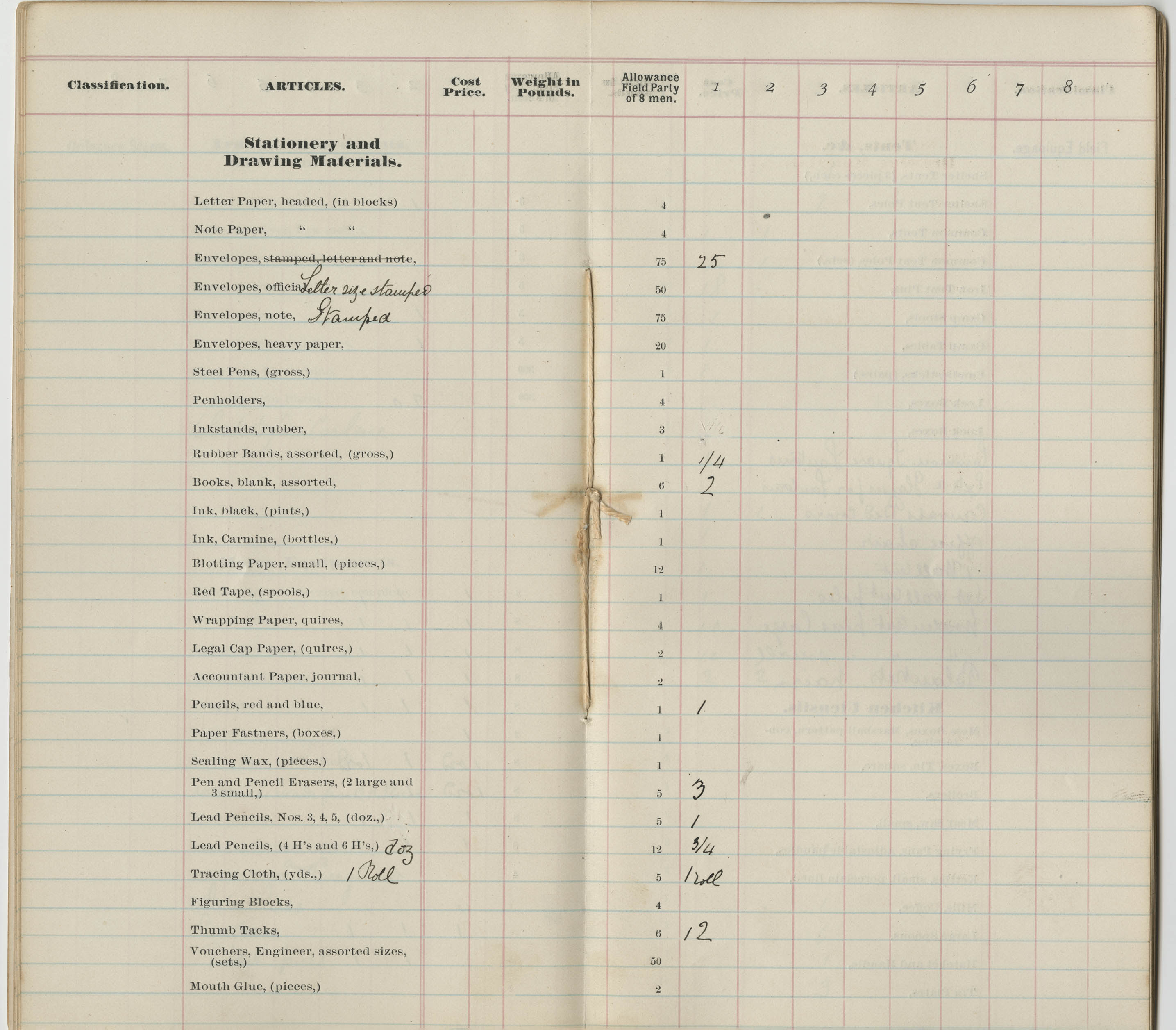

Supplies and Equipment

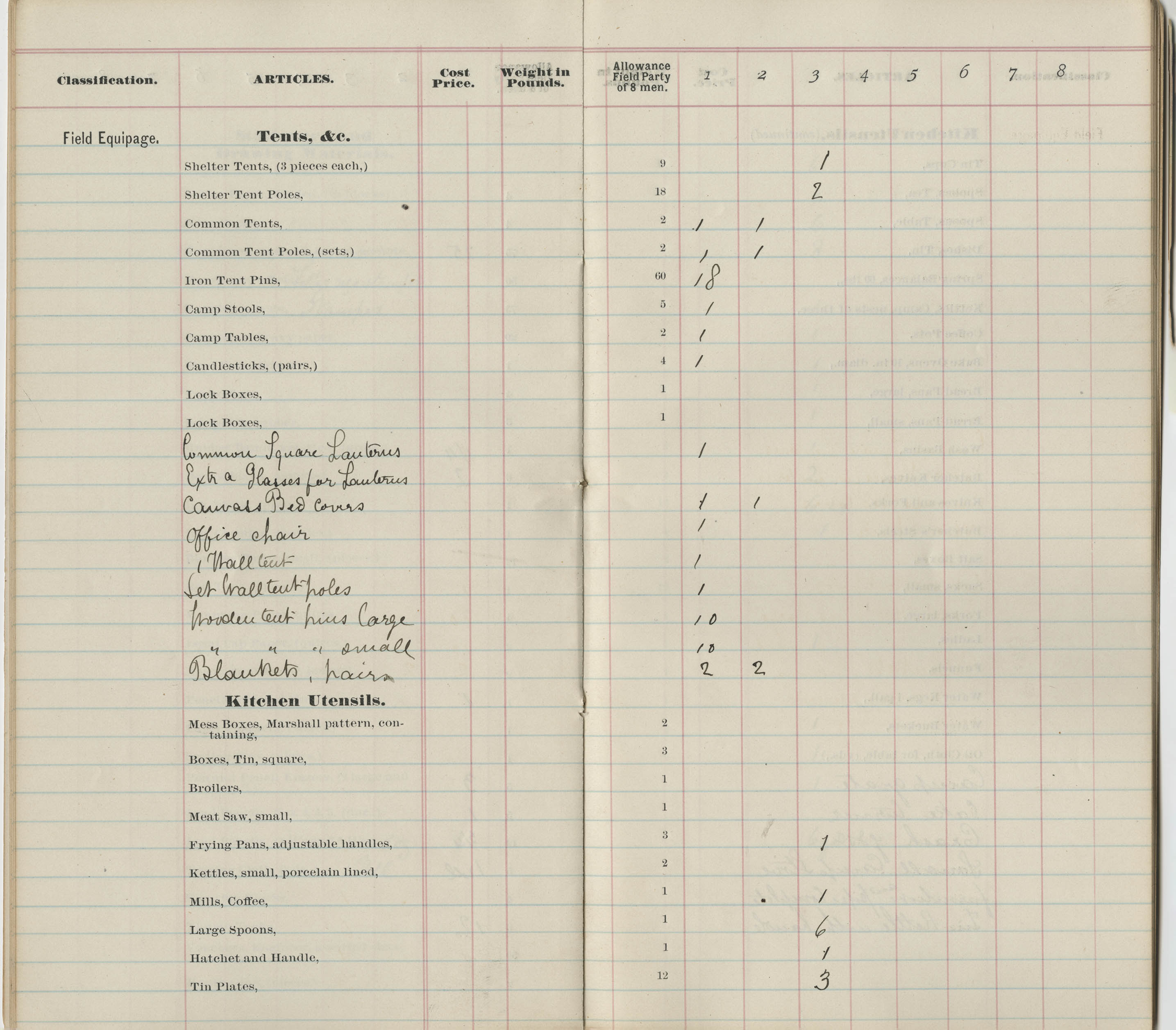

Using specially printed forms and notebooks, clerks recorded what each field party received in the way of surveying instruments, equipment, and supplies at their rendezvous camp at the beginning of each season and what was resupplied at various Army camps along their route. These supplies covered both camp life and surveying operations in the field for up to six months: equipment for horses and transportation, stationery and drawing materials, tents and camping equipment, kitchen utensils, and hand tools. The food rations issued for an eight-man party consisted of meat, salted ham and bacon, flour, beans, rice, coffee, tea, sugar, vinegar, salt, pepper, apples, peaches, pickles, yeast, potatoes, syrup, and canned tomatoes, all supplemented with items foraged in the field. Personal journals from this era make special note of the days when a rabbit or other game was had for dinner. A gallon each of whiskey and brandy were included in the teams’ medical supplies. The men also carried carbines, revolvers, pistols, and associated tools. Finally, survey parties travelled with riding mules, pack mules, and a lead female mule wearing a bell—a so-called “bell mare.”

|

|

|

|

Preprinted equipment lists for the Wheeler Survey recording the type and quantity of supplies from kitchen utensils to pencils. Office of History

|

| |

|

| |

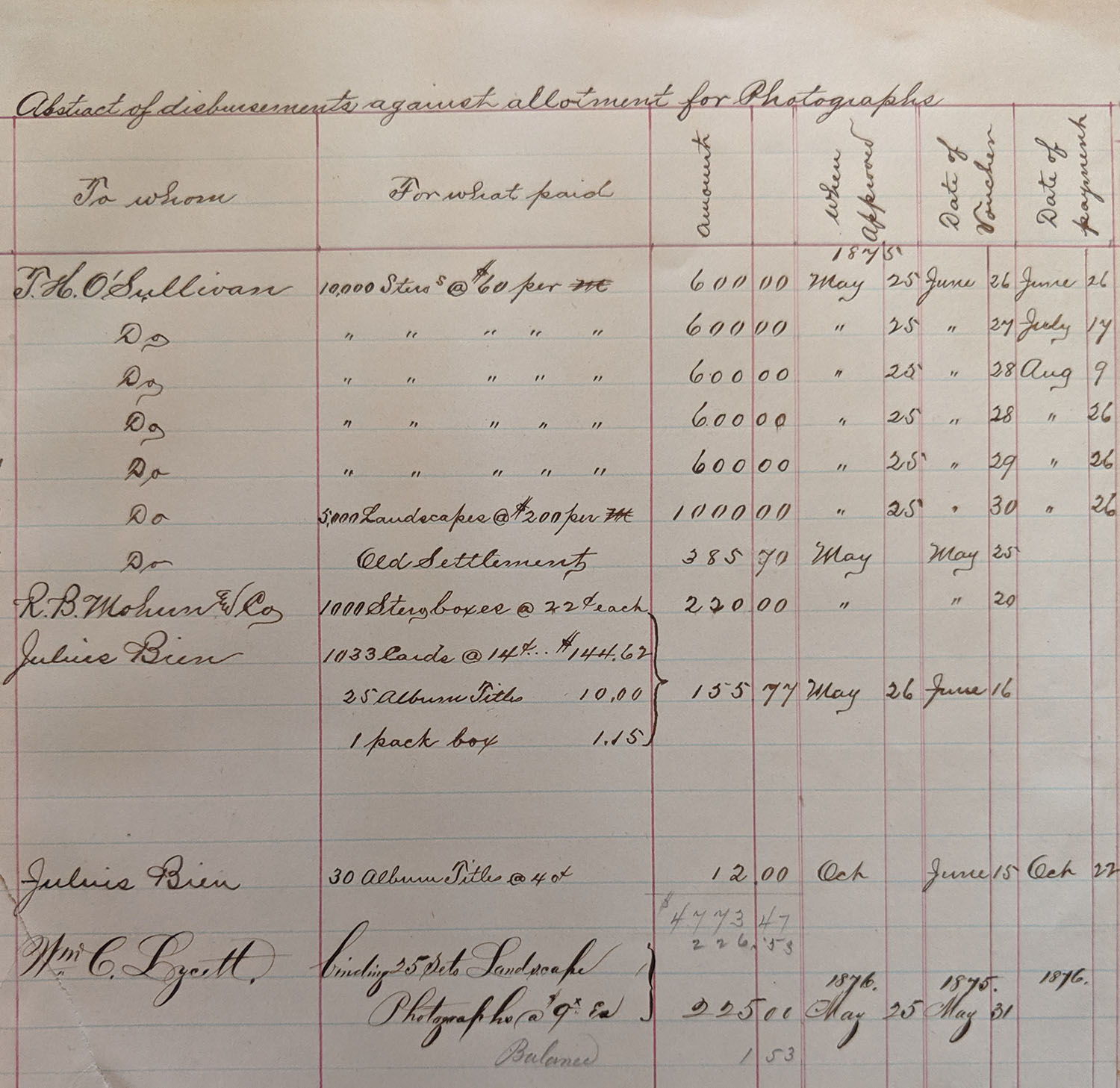

Tracking payments to survey party members. This page shows the disbursements to the survey’s official photographer, Timothy O’Sullivan. National Archives |

Exploring under the West’s Harsh Conditions

Wheeler’s survey parties faced many environmental hazards in the field. During summers, heat and lack of fresh water made the southwest’s arid deserts extremely dangerous for both the men and their animals. In 1875, Lt. Eric Bergland’s party experienced 100-degree heat in the shade while surveying in southeastern California. Several individuals wrote of the daily preoccupation with locating water sources in unchartered territories. Wheeler’s parties also faced terrible storms. While working in Colorado in 1874, Lt. William L. Marshall’s party suffered a two-day snowstorm in late September and then a four-day storm in early October. In April 1876, while surveying near Indian Wells in California’s Inyo Valley, Bergland’s party endured a three-day sandstorm that “penetrated eyes, ears, and nostrils, as well as instruments and provisions.” Traversing rugged terrain presented its own unique and dangerous challenges. Teams lost supplies and rations when boats and mules overturned, tossing their loads down mountains or into rivers. One exceptional loss was a few hundred glass plate photographic negatives taken by the survey’s professional photographer, Timothy O’Sullivan.

Despite the harsh environment, the Wheeler Survey experienced few casualties while in the field, although sickness was frequent. In 1874, E. J. Sommer, the chief topographer in Lt. Stanhope E. Blunt’s party, fell ill and was sent to the hospital at Fort Union. Luckily, he made a full recovery and returned to his party for the rest of the season. That same year, Henry W. Henshaw, a natural history collector, reported experiencing “malarial” weather and illness while in southern Arizona. Only two deaths were directly tied to the survey. The first was in November 1872, when an F. Kettleman supposedly died in Paria Canyon in Arizona. The second was that of Dr. F. Kampf, who suffered a head injury while surveying a baseline in Ogden, Utah, in 1877. He finished working that year, but succumbed to his injury in April 1878. The unforgiving conditions year after year in the field even took a toll on Wheeler himself. His declining health, extended leaves of absence, and ultimate death at the age of 62 were attributed to ailments contracted during his survey work out West. [Click to read the General Order announcing the passing of Wheeler likely due to declining health related to his years surveying in the West.]

The logistical challenges facing such a complicated and hazardous surveying mission were daunting but, nevertheless, Wheeler and his compatriots overcame them. Their nine years of mapping and investigating successfully added to the stock of common knowledge and facilitated American settlement of the West.

October 2021. No. 150.

Office of History's series of articles detailing the U.S. Geographical Surveys West of the 100th Meridian