George M. Wheeler: Biographical Sketch

| |

|

|

Cadet George Montague Wheeler,

USMA Class of 1866

USMA Special Collections and Archives

|

George Montague Wheeler was born on October 9, 1842, in Hopkinton, Massachusetts, to John and Miriam (Daniels) Wheeler. The fifth of seven children, he entered the U.S. Military Academy at West Point in 1862, only a year after the Civil War began.[1] He graduated in 1866, ranking sixth out of thirty-nine cadets in his class, and was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the Corps of Engineers.

His first assignment was to the U.S. Army’s California Department, headquartered in San Francisco under the command of Brig. Gen. E. O. C. Ord. One of his first duties was to explore the area around Point Lobos near San Francisco. In 1869, Ord sent Wheeler, now a first lieutenant, on his first independent reconnaissance into the deserts of Nevada and Utah. During this mission, Wheeler developed his vision of a grand survey of the American West.[2]

After completing his recon, Wheeler headed to Washington, D.C., to promote his ideas for western surveys, and he garnered the professional and financial support of Chief of Engineers Brig. Gen. Andrew A. Humphreys. In 1871, with orders in hand, Wheeler (then 29 years old) left for Nevada with a military escort and a small cadre of surveyors, scientists, assistants, cooks, and packers. [3] That summer, Wheeler led his party across Death Valley in eastern California and ascended the Colorado River.[4]

In 1872, Congress appropriated funding for George Wheeler’s work in the West, officially establishing the United States Geographic Surveys West of the 100th Meridian. Over the next few years, the survey greatly expanded in both territorial scope and number of personnel involved. In 1872 and 1873, Wheeler continued to lead field parties of his own, while subordinate Engineer officers led their own parties under Wheeler’s supervision. In 1874, as the number of parties grew to nine, Wheeler stopped commanding his own field party and assumed an entirely supervisory role, visiting individual parties as they worked in the field. This arrangement continued until the survey ended in 1879. When not in the field, Wheeler was back in Washington, D.C., overseeing the production of maps at the survey’s headquarters or working the halls of Congress and the War Department to secure funding for his venture, which was competing for resources and legitimacy with three other surveys of the West occurring at the same time.

|

|

|

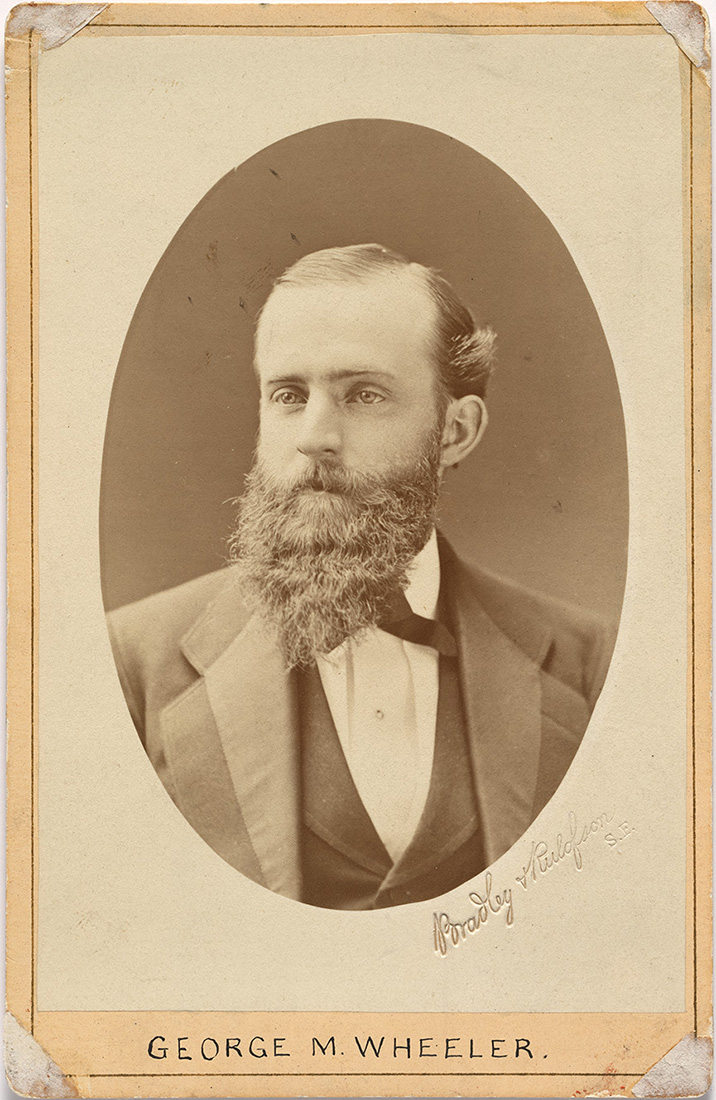

| George M. Wheeler, ca. 1872

National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

|

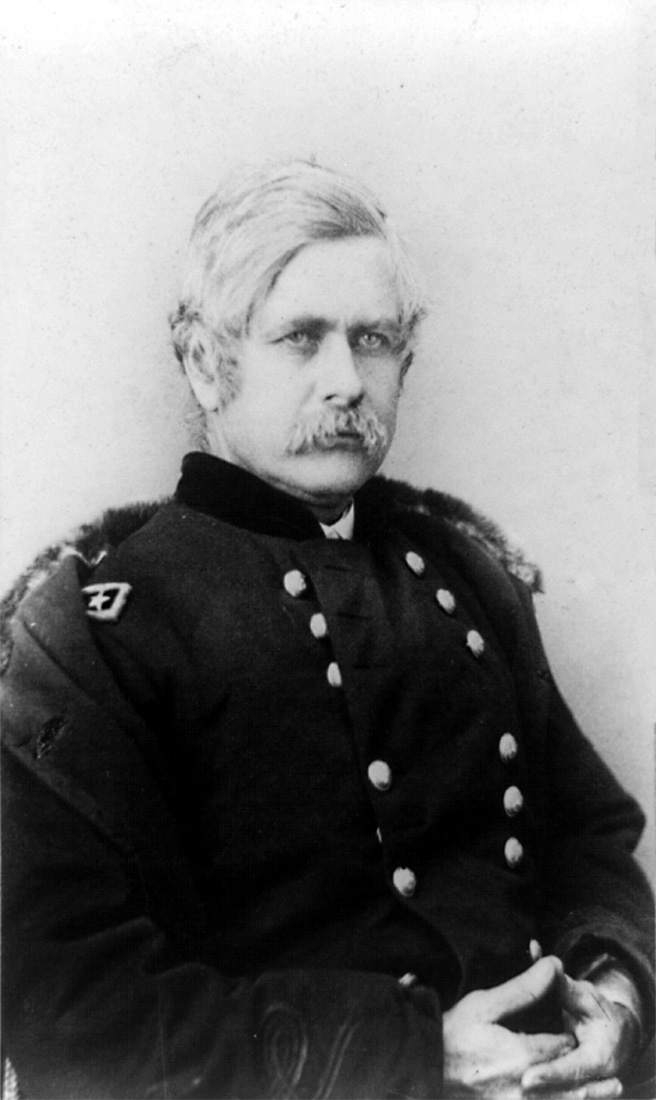

Ord, ca. 1861-1865, a few years before Wheeler

would have come under his command

Library of Congress

|

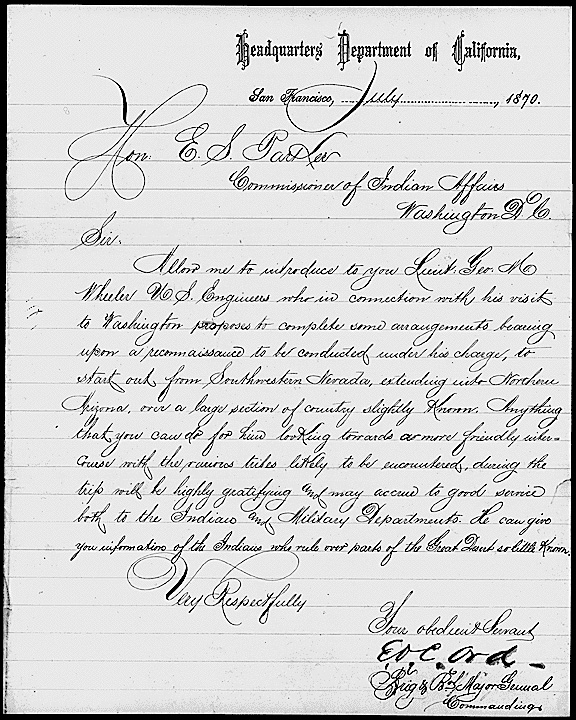

Wheeler's letter of introduction from Brig. Gen. E.O.C. Ord, Commander, Department of California, to the

Commissioner of Indian Affairs, Eli S. Parker, prior to the commencement of the Wheeler Survey.

National Archives, Records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs

|

George Wheeler’s time in Washington illustrates his ambition and willingness to challenge authority, a source of frustration for both Congress and General Humphreys. After a series of congressional investigations in early 1874 concluded Wheeler was duplicating the work of surveys led by Ferdinand V. Hayden and John Wesley Powell, Wheeler received only $30,000 from Congress out of the requested $95,000 for the 1874 season. In turn, he asked Humphreys for $60,000 from the unused balance of the “Appropriations for Surveys for Military Defenses for the fiscal year ending June 30, 1873,” a request Humphreys obliged. Congress and Humphreys also restricted Wheeler’s field operations to a smaller geographic area, forbidding him from encroaching on areas the Interior Department was surveying. After this episode, Wheeler became and remained bitter rivals with Hayden and Powell. [5]

|

|

Members of the Wheeler Party, 1870. George Wheeler is standing behind the porch railing, second from the left. His classmate and colleague Daniel Lockwood is second from left, seated in the front row.

Smithsonian Institution Archives |

|

Wheeler’s career floundered after the field operations of 1879. Though Wheeler was promoted to captain that year, he received no new authorities or commands. Over the next ten years, he continued supervising the production of atlas sheets, annual reports, and volume one of the survey’s final report. His only other significant assignment came in 1881 as the representative of the U.S. War Department at the Third International Congress and Exhibition in Venice, Italy. In the 1880s he began taking extensive leaves of absence due to his poor physical and mental health, and he eventually retired in June 1888. In May 1890, Congress authorized a promotion for Wheeler to major, retroactive to 1888.[6]

On December 16, 1874, George Wheeler had married Lucy James Blair, connecting Wheeler to a prominent Washington, D.C., family. Lucy was the daughter of James and Mary Serena Elizabeth Blair (Jessup) and the niece of Montgomery Blair (USMA 1835). James Blair was a Navy lieutenant and, like Wheeler, sought out exploration and scientific study. He served on the Charles Wilkes Antarctic Expeditions between 1838 and 1842. When the California Gold Rush hit in 1849, Blair made his wealth piloting ships around San Francisco harbor. His years of exposure in cold climates affected his health however, and in 1853 he died at 34 mere weeks before Lucy was born.

Records suggest that Lucy accompanied George out west and that the harsh conditions of their postings affected the health of them both. The Wheelers spent his retirement years between Washington, D.C., and New York. Lucy Wheeler died in Manhattan on February 3, 1902, at the age of 49 and was buried in the James Blair crypt in Rock Creek Cemetery in Washington. A little more than three years later, on May 4, 1905, George Wheeler also died in New York. They had no children. Wheeler’s final years were marked with poor health, caused by illnesses contracted during his years of surveying, and lawsuits owing to unpaid rents. He died penniless and was buried in a pauper’s grave. When Lt. Col. Daniel Lockwood, a former colleague and member of the survey in 1869 and 1871, heard of Wheeler’s burial, he arranged for him to be reburied at West Point.[7]

[1] Doris Ostander Dawdy, George Montague Wheeler: The Man and the Myth, (Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press, 1993), 5.

[2] William H. Goetzmann, Exploration and Empire: The Explorer and the Scientist in the Winning of the American West, (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1966); Dawdy, George Montague Wheeler, 7.

[3] A. A. Humphreys to George M. Wheeler, Departmental Instructions, March 23, 1871, in Geographical Surveys West of the One Hundredth Meridian, Volume 1: Geographical Report, ed. by George M. Wheeler, (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1889), 31-32.

[5] Goetzmann, Exploration and Empire, 481.

[6] Dawdy, George Montague Wheeler, 78.

[7] Dawdy, George Montague Wheeler, 80.

April 2021. No. 142b.

Office of History's series of articles detailing the U.S. Geographical Surveys West of the 100th Meridian