Headlines in the Johnson City Press,

12 Feb. 1944. Courtesy of newspapers.com |

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and its military and civilian personnel have always worked diligently to fulfill the agency’s vital and complex missions. This was true even during the Second World War when so much of the country, including of course the Army, focused its attention on national security and the defeat of fascism in Europe and totalitarianism in Asia. For the Corps of Engineers, that meant maintaining the nation’s waterways and responding to domestic crises.

In early 1944, while battles raged overseas at Anzio and Kwajalein, Corps employees near Memphis, Tennessee, were called upon to undertake a grim task. Just before midnight on February 10, a DC-3 airliner enroute from Los Angeles to New York (the Sun Country Special of American Airlines), having departed at 10:56 from a stopover in Little Rock, crashed into the Mississippi River about 18 miles southwest of the Memphis airport. There were no survivors.

Among the eight known witnesses to the plane’s descent was Charley Williams, a ship-keeper for the Corps of Engineers and the only one to see the actual crash. The engineers had been stationed on site at Cow Island Bend extending and repairing riverbank protection structures.

Williams was on duty as a watchman on a barge tied up on the Arkansas side of the river when he saw the doomed plane at only about 200 feet in the moonlit sky, traveling fast and at an angle, and whistling like a skyrocket. He recalled that the plane “exploded” when it hit the water about 300 yards from him; “a ball of fire rolled out in front” of the plane and it sank immediately. W. R. Wellborn, the engineer in charge of the revetment project, also heard the low-flying aircraft and felt large waves hit the barge after the crash. Before taking a boat to the scene, the men notified the Corps office at West Memphis of the disaster. From there Capt. H. K. Holloway relayed the report to airport officials. Williams and Wellborn found no trace of the airplane.

|

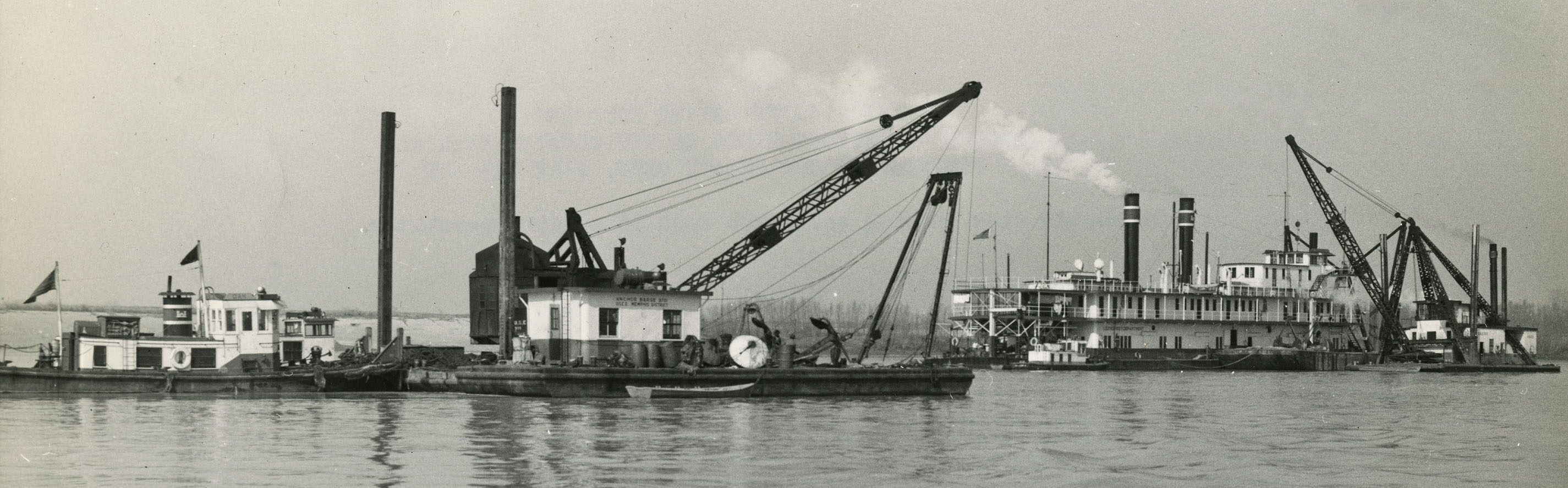

| Broad view showing engineer equipment used in the rescue operations — workboat Oak, an anchor barge, dredge Ockerson, and others. Office of History |

The U.S. Army Engineers immediately moved personnel and equipment to the site to search and salvage, using a barge with drag equipment and later a steam-powered dredge. Also on site was a U.S. Coast Guard unit, whose men searched the river on watercraft and scoured the banks. Several private citizens joined the search, and safety officials from the Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB) arrived in the morning. The engineers recovered the first piece of wreckage, the door of the plane’s cargo compartment, at 10:00 AM on the 11th. The Coast Guard also found equipment and baggage along the shore.

|

Some of the engineer floating plant involved in the salvage operations:

- At least one anchor barge

- Derrick boats #1412, #2309, and #3501,

with a chain rake drag

- Three workboats — Oak, Petrel, and Kildeer

- Steamship dredge Ockerson

- Snagboat Arkansas II

- Several smaller craft

- And: Coast Guard cutter Willow and other craft

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

|

|

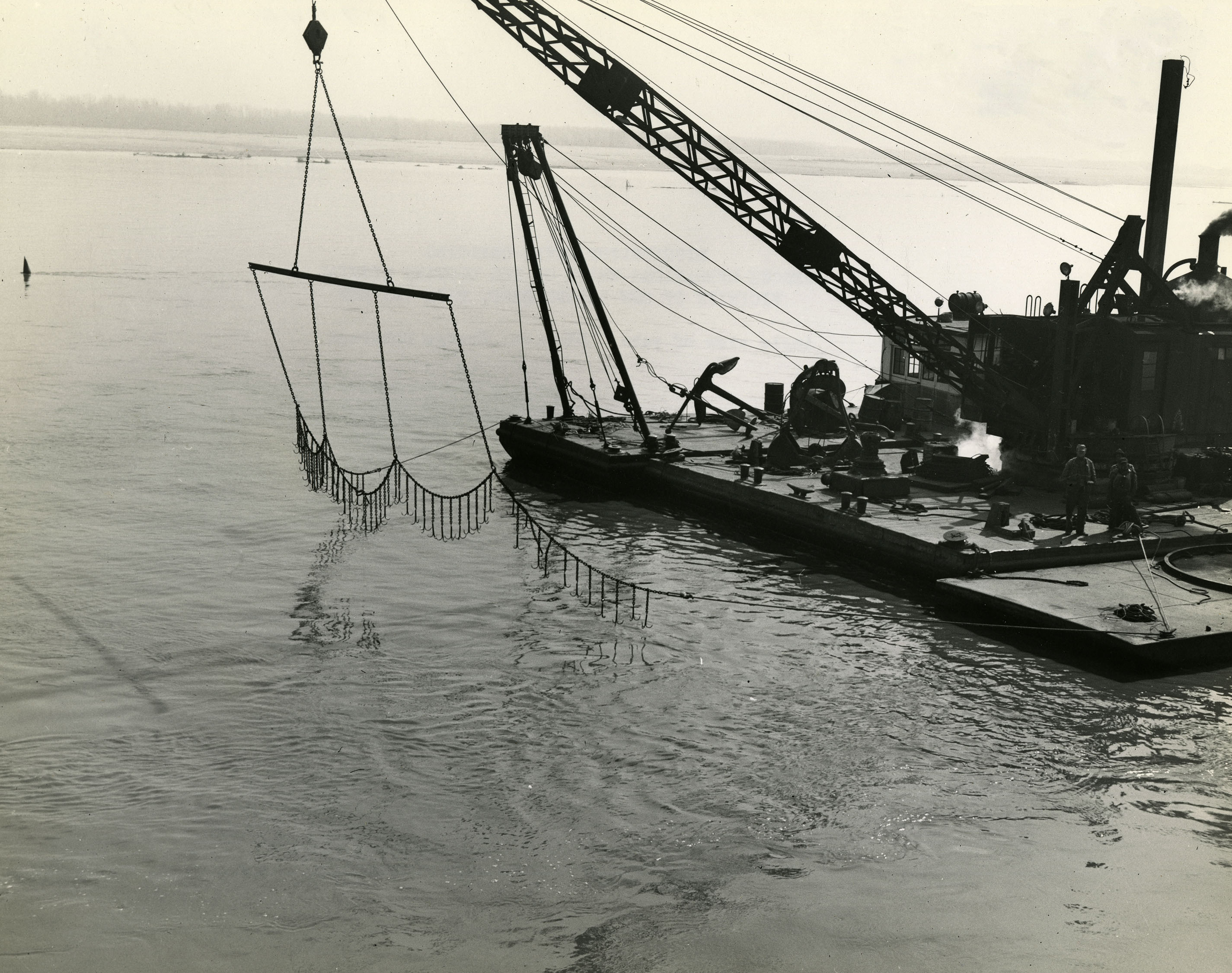

The chain drag rake attached to derrickboat #3501 for dragging operations. 19 Feb. 1944.

Office of History |

The site of the crash has seen other tragedies, including

riverboat fires and sinkings. For example, on May 8, 1925,

the Army engineer steamer Norman, just starting back

to Memphis after an excursion to Cow Island Bend, suddenly capsized and sank, killing 23 people. On board that vessel,

but surviving, were Memphis District Engineer Maj. D. H. Connolly and his assistant, Maj. Douglas Gillette. |

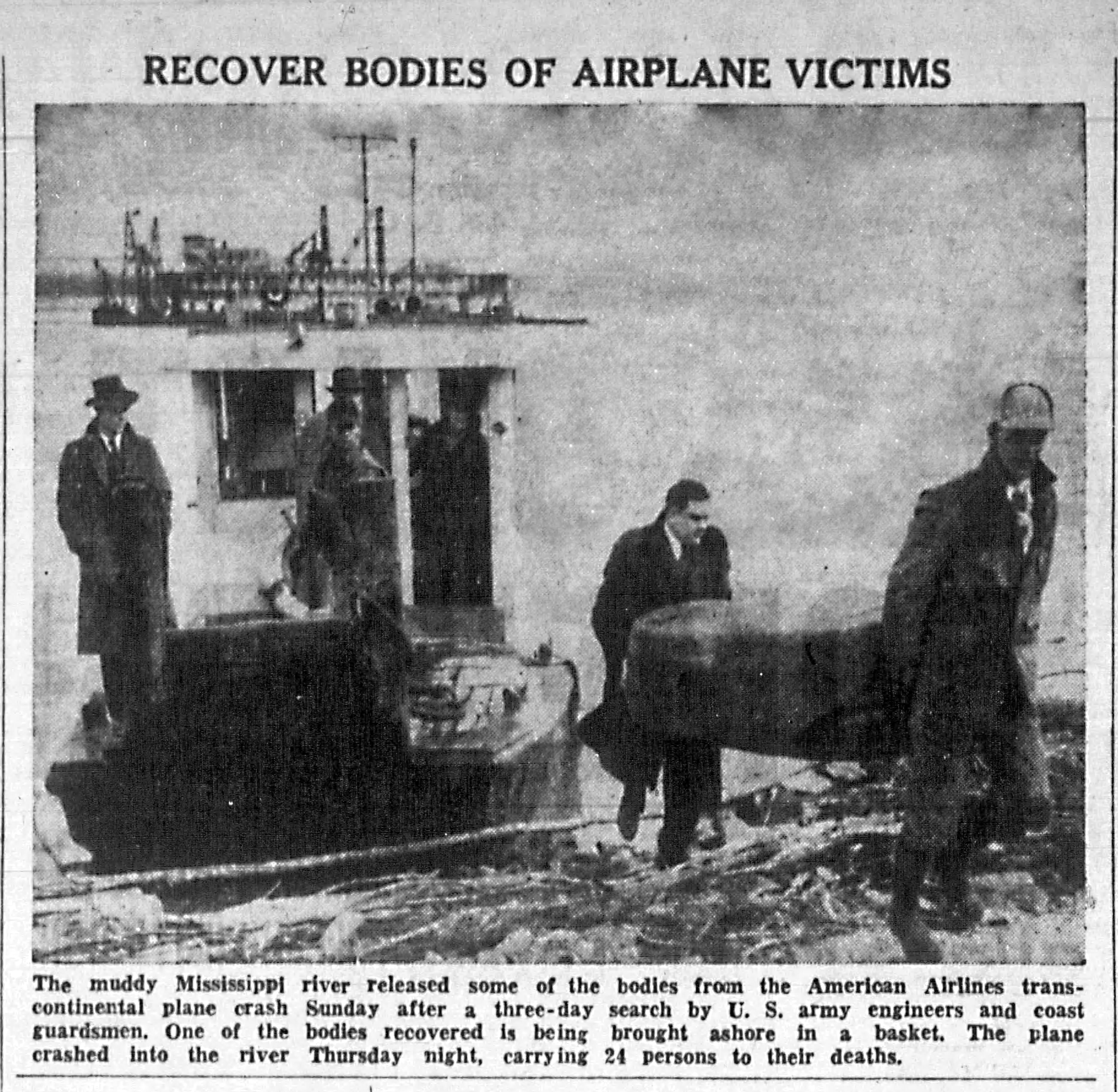

The clamshell basket of derrickboat #2309 depositing material on the steel barge attached to the dredge Ockerson, with the engineer snagboat Arkansas II in the left background and two Coast Guard vessels in the right background. Feb. 1944. Office of History |

Using grappling hooks, the engineers and the Coast Guard were at first able to recover only small aircraft pieces, mail, and luggage. The CAB later theorized that the plane’s speed at impact created a “shattering effect,” resulting in nearly total disintegration of the aircraft. Initially, salvagers were unsuccessful in locating any victims but soon recovered an engine, a propeller, part of the cockpit, and wing sections. The largest piece recovered was the badly damaged tail attached to 8-10 feet of fuselage.

On February 13, responders recovered five of the dead. Encouraged by this development, the engineers sent additional personnel and boats, including a second large dredge, to intensify the search. They retrieved a sixth victim the next day along with a wheel. On February 18, searchers found the co-pilot, the final victim discovered. Corps personnel ended salvage operations on the 21st – after having recovered 75-95% of the plane and seven of the deceased – announcing there was “slim possibility” of any additional recovery.

Twenty-one passengers (twelve of them active military, including one WAC) and three crew (two pilots and a stewardess) lost their lives in the disaster, making it the second-worst civil aviation accident to that point in terms of death toll. The CAB conducted investigations and hearings but never determined a probable cause for the crash, ruling out sabotage, bad weather, collision, and fuel shortage. Other possibilities also seemed unlikely or lacked evidence: engine malfunction, jamming of the controls, and collision with birds. The reason for the crash remains unknown today.

The board also praised the search effort: “The work of the United States Army Engineers and Coast Guard was highly commendable in that a large amount of the wreckage was salvaged under extremely difficult conditions.”

|

Part of an article from the Knoxville News Sentinel, 11 Feb. 1944. Courtesy of newspapers.com

|

Portion of the tail section of the plane at a Memphis District barge. Feb. 1944.

Office of History

A photo printed in the Bristol Herald Courier, 16 Feb. 1944.

Courtesy of newspapers.com

|

Recovered plane parts on the steel barge, with snagboat Arkansas II working in the background. Army engineers kept the recovered pieces under guard until CAB investigators had thoroughly examined them. Feb. 1944. Office of History

|

Recovery of the right propeller attached to the nose section. Feb. 1944.

Office of History |

See also an article about Memphis District employees who lost their lives serving overseas during World War II.

For more on the Corps of Engineers' emergency operations mission, see the Office of History publications Situation Desperate (Origins to 1950) and Destruction Imminent (1950 to 1979).

* * *

March 2023. No. 160.