Hurricane Agnes ranks among the most devastating meteorological events ever to assail the nation’s eastern seaboard. The Category 1 storm spread its destruction far and wide for a period of ten days in June 1972. It slammed into the Florida panhandle on June 19 sparking eighteen tornadoes, killing nine people, and causing millions of dollars in damages. Agnes then soaked states of the Deep South before returning to sea in Virginia as a tropical depression. But, instead of blowing out to sea, the rain-drenched system turned north and began creeping up the East Coast, pausing at Long Island and gathering strength. “We have a major disaster developing,” the Emergency Operations Center at the Corps of Engineers Headquarters reported as it monitored the storm.

| |

|

| |

Rainfall totals from Agnes. NOAA Weather Prediction Center. |

Growing again into a tropical storm on June 22, Agnes looped inland along the Pennsylvania–New York border, dumping heavy rains on the Susquehanna, Schuylkill, and Allegheny River basins and Genesee and Chemung Rivers of New York before finally disappearing into Canada. While wind damage had been relatively mild, rainfall was torrential, averaging eight to twelve inches over twenty-four hours and topping eighteen inches in some locations. The resulting flooding over such a wide area made Agnes the costliest disaster up to that time. More than one hundred died as rains and floods swept away homes, farms, and businesses. The Susquehanna, Shenandoah, and Potomac Rivers topped their banks, destroying more than 43,000 structures and forcing 350,000 to evacuate their homes. As one Corps pamphlet noted, “For some obscure reason tropical storms are named for ladies. Agnes was no lady.”

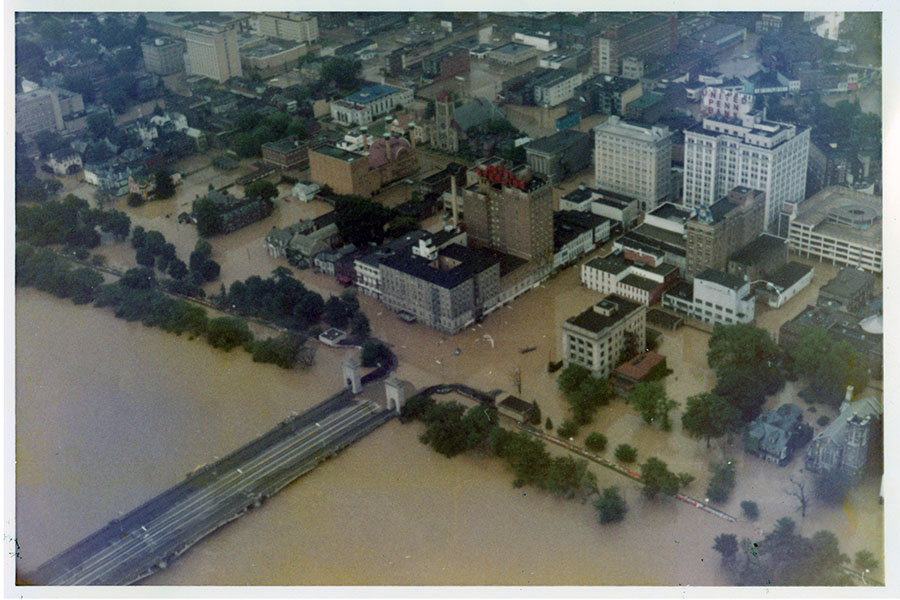

On June 24, Lt. Gen. Frederick Clarke, USACE Chief of Engineers, pronounced Hurricane Agnes “the worst natural disaster in the history of the country.” He accompanied members of Congress on an aerial survey of the flooding and storm damages. Attention soon centered on the metropolitan area of Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, where hundreds were trapped in their homes. The Baltimore District responded at once and with vigor, dispatching survey and rescue teams. As recovery work got under way, the Corps set up fourteen disaster area offices in a hard-hit, four-state region. Soon, workers with buttons proclaiming that “The Corps Cares” seemed to be almost everywhere. At the suggestion of Maj. Gen. Richard H. Groves, North Atlantic Division Engineer, the chief of engineers set up a temporary USACE district—the Susquehanna District—to handle the large-scale disaster relief. The new district quickly set about clearing debris, housing refugees, repairing homes, and helping to make the battered region livable once again.

During the storm, the Corps opened all fifty-three floodgates on the Conowingo Dam on the Susquehanna in Maryland for the first time in forty years. The dam held, but floodwaters caused $2 million in damages in the area. In Pennsylvania alone, floods washed out 200 bridges, destroyed 4,300 homes, damaged another 63,000, and caused more than $2 million in commercial damages. Col. Lewis Prentiss, Jr., of the Baltimore District arrived at Wilkes-Barre with his staff and established a command post as flood waters from the storm overtopped levees. As waters receded, he initiated the processes of removing flood debris and restoring stream channels, deploying Bailey bridges where advisable, and repairing bridges and water-sewer systems. Also, for the first time since passage of authorizing legislation (PL 91-606) in December 1970, the new district prepared mobile home sites for temporary housing provided by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. When state governments furnished land for mobile home parks, the Corps began construction. It typically required five days to design a park with concrete pads, drives, and utilities, four more days to prepare and award a construction contract, and about a month to build a park. In the meantime, 12,000 evacuees were living in shelters and after two weeks grew increasingly impatient and began organizing protests. By June 28, the Corps had 65 contracts underway, and by mid-July 1,070 contractors were at work; eventually the Corps let 4,511 emergency contracts for $102.7 million.

|

Flooding in Wilkes-Barre, Pa., after Hurricane Agnes, 1972.

Office of History. |

In early August, President Richard Nixon shrewdly appointed Wilkes-Barre native Frank Carlucci, a deputy at the Office of Management and Budget, as federal disaster coordinator. Carlucci opened his office at Wilkes-Barre, and the Susquehanna District moved its headquarters to the town shortly thereafter. He held morning staff meetings with the Corps and other agencies, made formal decisions after each meeting, and then toured the disaster area daily to inspect progress. It was ultimately Carlucci who developed the framework for the Agnes Disaster Recovery Act of 1972 (PL 92-385). This law provided liberalized loan provisions and authorized grants to nonprofit educational organizations not covered by previous laws. Working with the administration, Carlucci also pushed through a supplemental budget request of $1.5 billion for the disaster relief fund.

By the time Nixon visited Wilkes-Barre in early September, the Corps had completed twenty-eight mobile home parks in the area, and many evacuees left shelters as Housing and Urban Development brought in the trailers in time for children to start school. The Norfolk District completed four mobile home parks in Virginia. Meanwhile, contractors had razed 1,500 buildings at a cost of $1.2 million even as repairs continued. As the Susquehanna District completed its last tasks in the fall, it consolidated offices and turned over missions to the Baltimore District. Finally, after it completed its work and closed out contracts on November 21, 1972, Groves closed the Susquehanna District on the last day of November after a little more than four months in existence. The Corps performed a total of $150 million in restoration work and another $7 million in inspections of work by others. Although some recovery work continued, it fell to the existing districts to complete ongoing missions, while Carlucci coordinated with two Federal Regional Councils for long-range planning, encouraging them to approve loans to supplement disaster relief spending.

|

|

|

Frank Carlucci, federal disaster coordinator after Hurricane Agnes,

arrives in Wilkes-Barre, Pa., 1972. Office of History.

|

Coal Brook Trailer Park, Pa., after Hurricane Agnes, 1972.

Office of History. |

With total damages nationwide estimated at $3.1 billion ($21.7 billion in 2022), Hurricane Agnes was the costliest disaster to that time, less from its severity than the widespread nature of the resulting floods. Throughout its response effort, the Corps demonstrated its ability to mold military and civil elements—its own personnel, contractors, troops—into a unified force working to help the region recover. Military discipline ensured speed of response. Decentralization facilitated access to accurate information on local problems and local contractor capabilities. Decisions were made quickly. The nationwide Corps organization formed a pool of talent from which overburdened districts drew help. Flexibility, training, speed, unity——these factors made the engineers an essential part of the nation’s response to the ruin caused by storms over the course of more than a hundred years.

For additional information on the Susquehanna District, see Paul K. Walker’s The Corps Responds: A history of the Susquehanna Engineer District and Tropical Storm Agnes.

For more on the Corps of Engineers' emergency operations mission, see the Office of History publications Situation Desperate (Origins to 1950) and Destruction Imminent (1950 to 1979).

***

July 2022. No. 153.