|

| Damage to San Francisco |

At 5:16 on the morning of April 18, 1906, a devastating magnitude 7.8 earthquake struck San Francisco, California. Among those jolted awake was Brig. Gen. Frederick Funston, commander of the Army’s Department of California. He surveyed the damage and, without a declaration of martial law, decided to call out troops to guard federal property and assist city police and firemen. Orders went out to the commander at the Presidio and to Capt. Meriwether L. Walker, engineer officer and commander at Fort Mason. Located at Van Ness Avenue and Bay Street, it was the nearest garrison to downtown San Francisco.

Directed to report to the city’s Hall of Justice, Walker roused his men—five officers and 150 troops of the First Engineer Battalion, Companies C and D. Leaving one officer and twenty-four men to secure the fort, he led the remainder at breakneck speed to their destination. As ordered, each carried a rifle and twenty rounds of ammunition.

The engineers were the first to arrive, followed soon by other federal troops and the California National Guard. They were placed on street patrol. Although the task was dangerous, they remained on duty without a break for more than twenty-four hours. One engineer broke up a crowd of looters. Another carried out his patrol as exploding gas sent manhole covers flying and buildings crashed to the ground.

Eventually windswept fires forced a retreat and Funston ordered the engineers back to Fort Mason. While Walker and his men patrolled the city, thousands of quake victims overran Fort Mason seeking shelter, food, and water. Night patrols were required to control the crowds who filled available tents and jammed the barracks. Lieutenant Bain opened the post hospital, and later the barracks, to care for the sick and injured.

Early on the 20th Walker was forced to divert his men to save Fort Mason from the advancing fire. In a valiant effort, engineers created a barrier between fire and fort, organized a bucket brigade, and restored a damaged fire engine just in time to check the flames at the Van Ness barrier. Their actions were credited with saving the western part of the city.

|

| William W. Harts as a Brig. Gen. |

Walker and his troops were not the only engineers on duty in San Francisco. Col. William H. Heuer, commander of both the Pacific Division and the San Francisco District; Col. William H. Harts, director of the California Debris Commission; and Col. Charles McKinstry, the chief engineer of the Army’s Pacific Division, inspected structural damage, handled relief supplies for the Quartermaster Department, and dynamited buildings.

Relief and recovery operations shifted into high gear on the 21st when Maj. Gen. Adolphus W. Greely, commander of the Army’s Pacific Division, assumed direction of the operations and established his disaster headquarters at Fort Mason. Assisted by Red Cross workers, the engineers served meals around the clock, established tent camps, dug latrines, and enlisted “residents” to pick up trash.

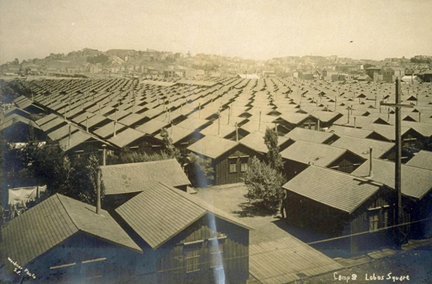

General Greely assigned engineers a primary role in providing temporary housing. Two officers designed a camp at Lobos Park consisting of 850 wall tents, four shower/bath houses, four large mess buildings, an administration and storage building, and privies. Using a shipload of lumber from the Quartermaster Department, the engineers directed a 200-man workforce that built the camp, piped in water, and had it ready to open by May 1.

Colonel Harts and the Corps’ Pacific Division staff also prepared designs for prefabricated wooden buildings using three standard designs. Harts preferred the single-family unit design because the benefits of comfort and privacy outweighed the cost. The Red Cross accepted Harts’ recommendation and contracted for 6,200 cottages able to house 20,000. Eventually the occupants were allowed to move their cottages from camp sites to private property for permanent use.

Cottages at Lobos Square

Greely also used the engineers to dynamite ten buildings. A sergeant in the battalion narrowly escaped death when the McCormick Hotel collapsed as he was placing a dynamite charge in the basement. Harts, Heuer, and McKinstry helped plan how to restore public utilities and transportation, but provided only technical advice once local companies proved capable of handling the situation.

Members of the First Engineer Battalion and engineer officers and civilians stationed in San Francisco were an important part of the U.S. Army’s response to the 1906 earthquake. General Greeley maintained that the Army’s efforts “illustrated the value, in an emergency, of a trained, organized force.” In the May 12, 1906, issue of Harper’s Weekly the editors wrote: “The business of the Army is to meet emergencies, and in such a case as that of San Francisco its training and its system are invaluable.”

Lobos Square image from: Western Neighborhoods Project.

For more on the Corps of Engineers' emergency operations mission, see the Office of History publications Situation Desperate (Origins to 1950) and Destruction Imminent (1950 to 1979).

* * *

April 2006. No. 101.