For more than a century, victims of hurricanes have looked to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers for crucial aid. Corps rescue work on the Gulf of Mexico dates back to 1875, when workers at Galveston manned boats to save storm victims caught in the raging waters off Fort Point. Engineer planning dates to 1900, when retired Chief of Engineers Brig. Gen. Henry M. Robert gave Galveston its first protection plan. Enactment in 1950 of a federal disaster relief program brought the Corps heavy responsibilities but also demonstrated the fitness of the traditional engineer organization to cope with new tasks.

For more than a century, victims of hurricanes have looked to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers for crucial aid. Corps rescue work on the Gulf of Mexico dates back to 1875, when workers at Galveston manned boats to save storm victims caught in the raging waters off Fort Point. Engineer planning dates to 1900, when retired Chief of Engineers Brig. Gen. Henry M. Robert gave Galveston its first protection plan. Enactment in 1950 of a federal disaster relief program brought the Corps heavy responsibilities but also demonstrated the fitness of the traditional engineer organization to cope with new tasks.

n 17 August 1969, Hurricane Camille crossed the Mississippi coast with winds of 201 miles per hour and a storm surge some 24 feet above sea level. In its path, steel and concrete buildings, venerable homes, and deep-rooted oaks were simply obliterated. As the storm passed, engineers swung into action. The New Orleans District did superb work south of the city and also assisted the Mobile District that was responsible for most of the work along the Gulf coast and inland. Mobile District officials sent civilian contractors into the devastated areas to clear roads. Engineer troops from Fort Benning, Navy Seabees, and airmen from Keesler Air Force Base joined in. Aided by these forces, the district removed rubble, recovered bodies, cleared trees, freed 14,000 residential lots of debris for rebuilding, and dredged 12 million cubic yards of shoaling from Gulf harbors.

|

|

|

| Soldiers participate in debris removal during recovery operations |

|

Maj. Gen. Morris (second from left) and Lt. Gen. Clarke

visit Wilkes-Barre, Pa., following Agnes |

Tropical Storm Agnes was one of the most devastating storms to hit the nation’s eastern seaboard in the twentieth century. Between 14 and 23 June 1972 more than 100 died as torrential rains and floods swept away homes, farms, and businesses. Property damage totaled more than $3 billion. The Susquehanna, Shenandoah, and Potomac Rivers topped their banks. Wilkes-Barre was engulfed. The Baltimore District responded at once, dispatching survey and rescue teams to aid the beleaguered city. As recovery work got under way, 14 disaster area offices were set up in a hard-hit four-state region. Soon, workers with buttons proclaiming that “The Corps Cares” seemed to be almost everywhere. At the suggestion of Maj. Gen. Richard H. Groves, North Atlantic Division Engineer, the Chief of Engineers, Lt. Gen. Frederick J. Clarke, set up a new district to handle disaster relief. In a busy three-month life span, the Susquehanna District cleared debris, housed refugees, repaired homes, and helped to make the battered region livable once again.

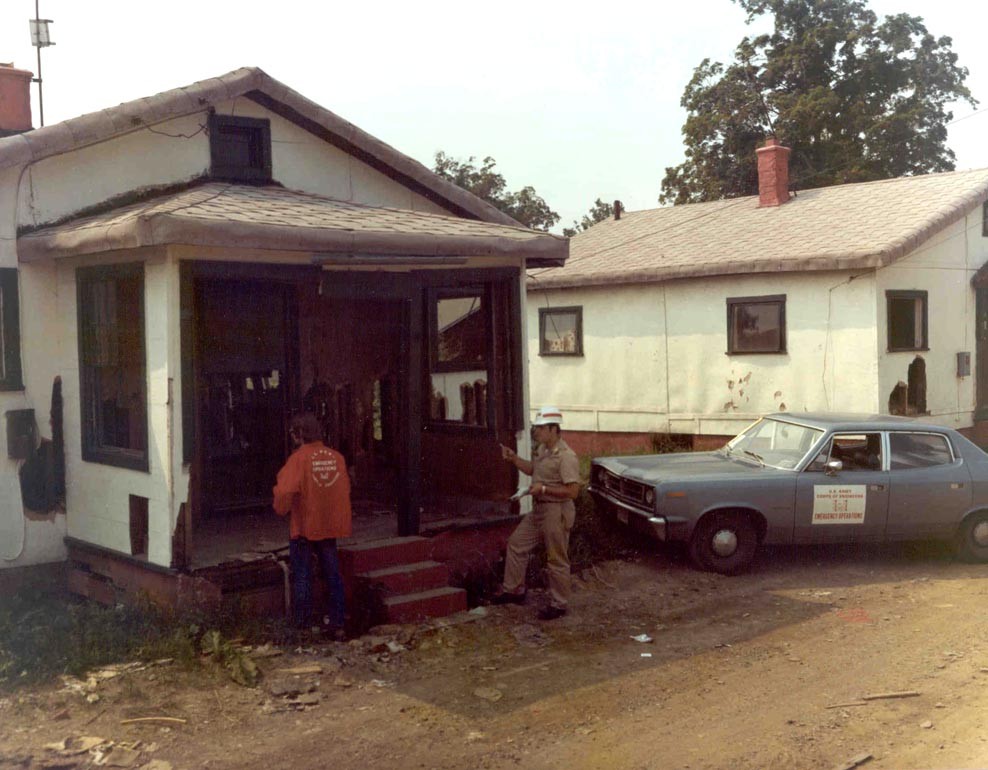

The Corps' Emergency Operations "Agnes" Disaster Survey Team,

New York District, inspect damaged homes

In both crises, the Corps demonstrated its ability to mold military and civil elements—its own personnel, contractors, troops—into a unified force working for recovery. Military discipline ensured speed of response. Decentralization aided the district’s intimate knowledge of local problems and local contractors’ capabilities. Decisions were made quickly. The nationwide Corps organization formed a pool of talent from which overburdened districts could and did draw help. Flexibility, training, speed, unity—these factors in the course of 100 years made the engineers an essential part of the nation’s response to the ruin caused by hurricanes.

For more on these disaster responses see:

USACE New Orleans, Mobile, Galveston, and Baltimore District histories.

“Camille and the Engineers,” The Military Engineer, 61 (1969), 407-409.

The Corps Responds: A History of the Susquehanna Engineer District and Tropical Storm Agnes. Dr. Paul K. Walker. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Baltimore District, ND. HQ, USACE

For more on the Corps of Engineers' emergency operations mission, see the Office of History publications Situation Desperate (Origins to 1950) and Destruction Imminent (1950 to 1979).

* * *

August 2003. No 73.