| |

|

| |

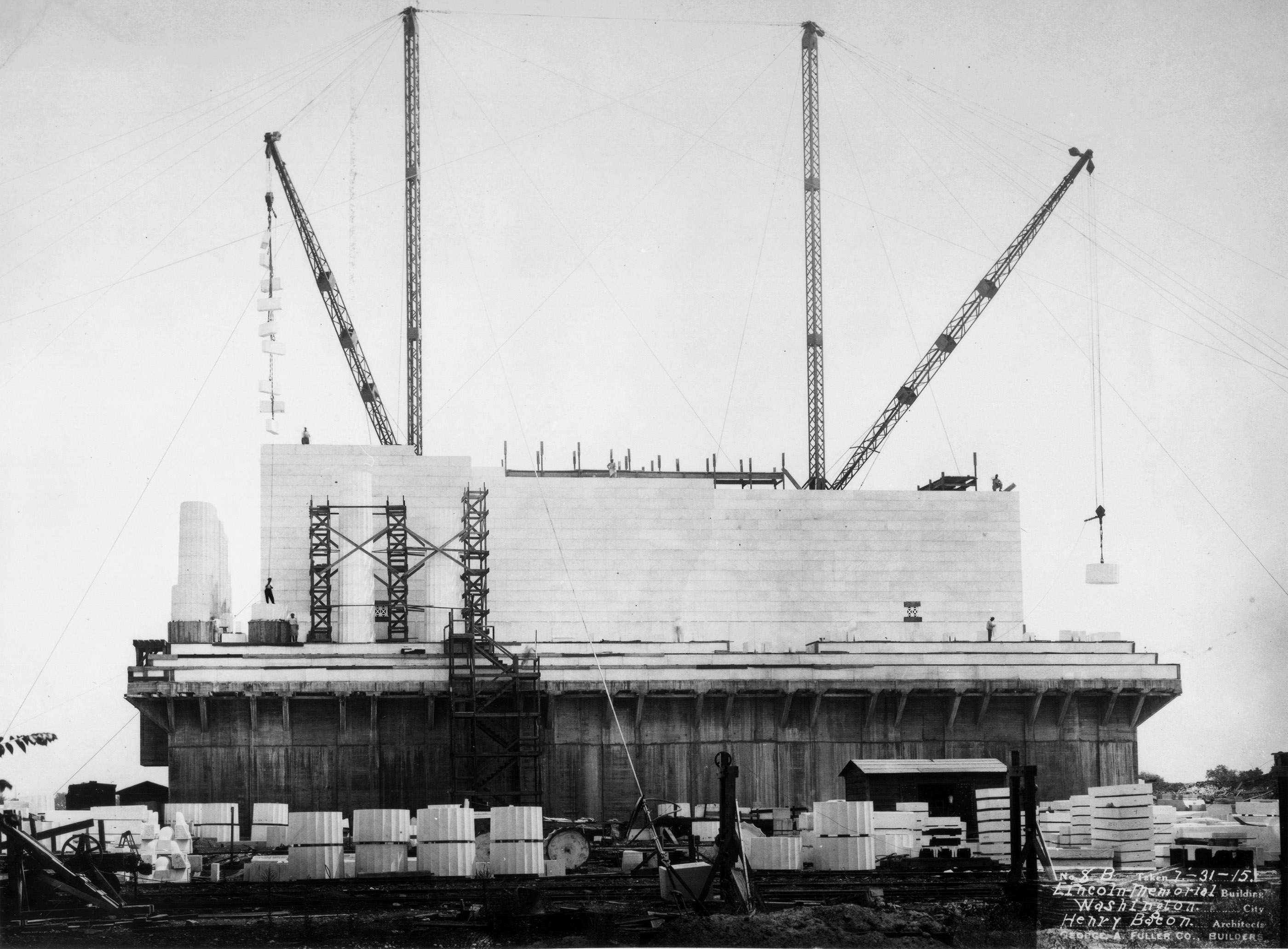

The final structural design called for sub-foundations of reinforced concrete poured into cylindrical steel piers driven through the unstable fill to bedrock 65 feet below. Upper foundations of concrete columns would support the memorial’s floor, and earth fill would cover these columns to form a terrace around the building. Here, several metal cylinders are in the foreground, some of them topped by heavy weights to help drive them downward, Sep. 1914. National Archives, 66-G-23P-47 |

Among the most notable landmarks in Washington, D.C., are its many extraordinary monuments and memorials, many of which went up in the 19th and 20th centuries with the help of Army Engineers. Congressional commissions established to manage various memorialization efforts usually delegated the day-to-day supervision of construction to the Office of Public Buildings and Grounds (OPBG), an independent office that managed federal land in the capital and reported directly to the Chief of Engineers. Army officers from the Corps of Engineers led the OPBG and its successor throughout its existence (1867–1933).

Background

In 1911 Congress appointed several prominent politicians to a Lincoln Memorial Commission (LMC) and charged it with honoring the nation’s 16th president, Abraham Lincoln. As required by law, it turned to the newly formed Commission of Fine Arts (CFA) for advice on locating and designing the proposed memorial. The CFA was composed of architects and artists, but the head of the OPBG served as its secretary, executive, and disbursing officer. The LMC very soon also selected the public buildings chief to act as its disbursing officer and executive. Thus, Army Engineer officers became key players in the development of the Lincoln Memorial in both its design (CFA) and its construction (LMC) while also serving as a conduit between the two commissions.

Four Engineer officers of the OPBG served as commission secretaries and executives during this period. They were Cols. Spencer Cosby, William W. Harts, Clarence S. Ridley, and Lt. Col. Clarence O. Sherrill.

Site and Design

Over the next several months, the two independent commissions held quite different opinions about preferred location, design, and architect. Cosby, as the Army Engineer head of the OPBG, dutifully served both commissions, learning the sentiments and strategies of both and communicating engineering data to all the members. Eventually a decision was reached where to site the memorial and to engage an architect. Congress formalized the decision in early 1913, at which point Crosby shifted focus from design to construction.

The two commissions had been at odds over the site, and thus the design, of the planned memorial. The CFA preferred a location at the western end of the Mall on recently reclaimed land. Members of the LMC felt the area could never be made adequately beautiful and suggested other sites. Then, eschewing the normal practice of holding a competition, the CFA asked then-unknown architect Henry Bacon to submit a design. Meanwhile, the LMC authorized Cosby, as its executive, to contract with architect John Russell Pope to design Lincoln memorials for two alternate sites. Although Cosby preferred Bacon and the Mall site, he continued to serve dutifully both commissions.

In early 1912 the Commission of Fine Arts made a decisive determination on the Mall location and ultimately won over the Lincoln Memorial Commission as well. The CFA then asked both architects to refine their designs for the chosen location. After careful consideration, it recommended Bacon’s proposal. The LMC eventually signed off as well, and by early 1913 Congress approved the resolution to build Bacon’s memorial on the Mall site. Subsequently, Crosby transitioned from intermediary in this quasi-competition to supervisor of the memorial’s construction.

|

|

|

|

The upper foundations serve as a platform for the memorial structure, Mar. 1915. The National Foundation & Engineering Co. and M. F. Comer of Toledo, Ohio, were the contractors for the foundations. National Archives, RG 42

|

|

Walls and columns of the superstructure taking shape, Jul. 1915. The George A. Fuller Co. was the contractor for the memorial building. National Archives, RG 42, No. 8B

|

Construction

On October 1, 1913, shortly after construction bids were opened, Harts succeeded Cosby in the OPBG and on the commissions. He spent the next four years approving the selection of materials and managing the Lincoln Memorial’s construction from foundation to frieze. He supervised everything from the complicated substructure (a challenging issue for such a weighty building erected on land created from dredge fill) to the decorative carving.

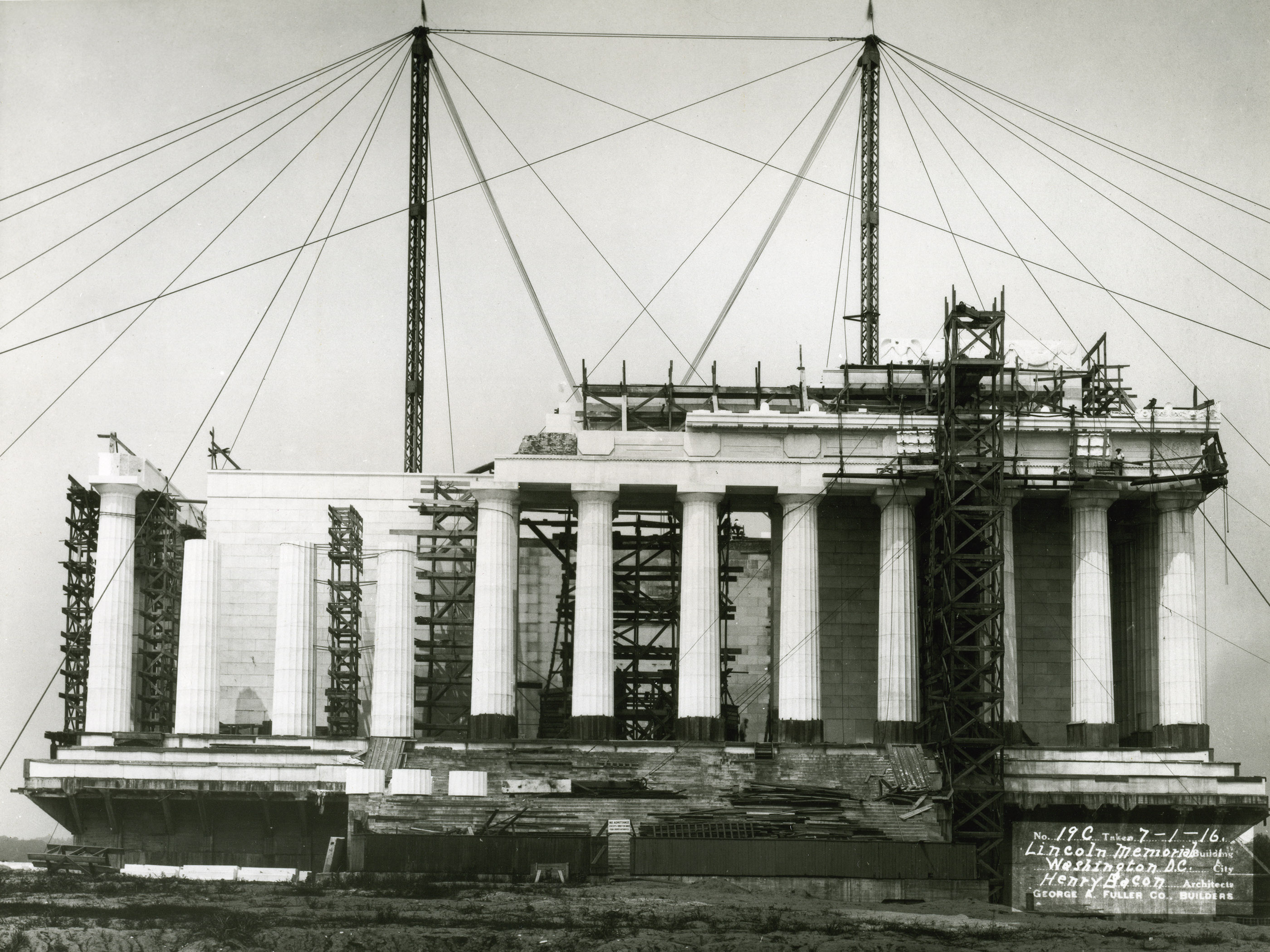

In October 1918 the colonnade was finished, by then under the direction of Ridley, and the structure practically completed by November 1919, when excavation began for the Reflecting Pool. By December, sculptor Daniel Chester French had finished his statue and seen it placed. On January 1, 1920, the Chief of Engineers assumed the care and maintenance of the memorial, and on June 21, 1921, it opened to visitors. In 1921–22, under Sherrill, the OPBG continued to grade and landscape the area, installed paved roadways and sidewalks, and underpinned the terrace wall.

|

|

|

|

The main building of the memorial nearing completion, Jul. 1916.

National Archives, 77-DP-100A-3, 19C

|

|

Afternoon ceremonies to dedicate the Lincoln Memorial, May 30, 1922. Chief Justice and former President William Howard Taft, who had sat on the LMC, presided over the festivities. Office of History

|

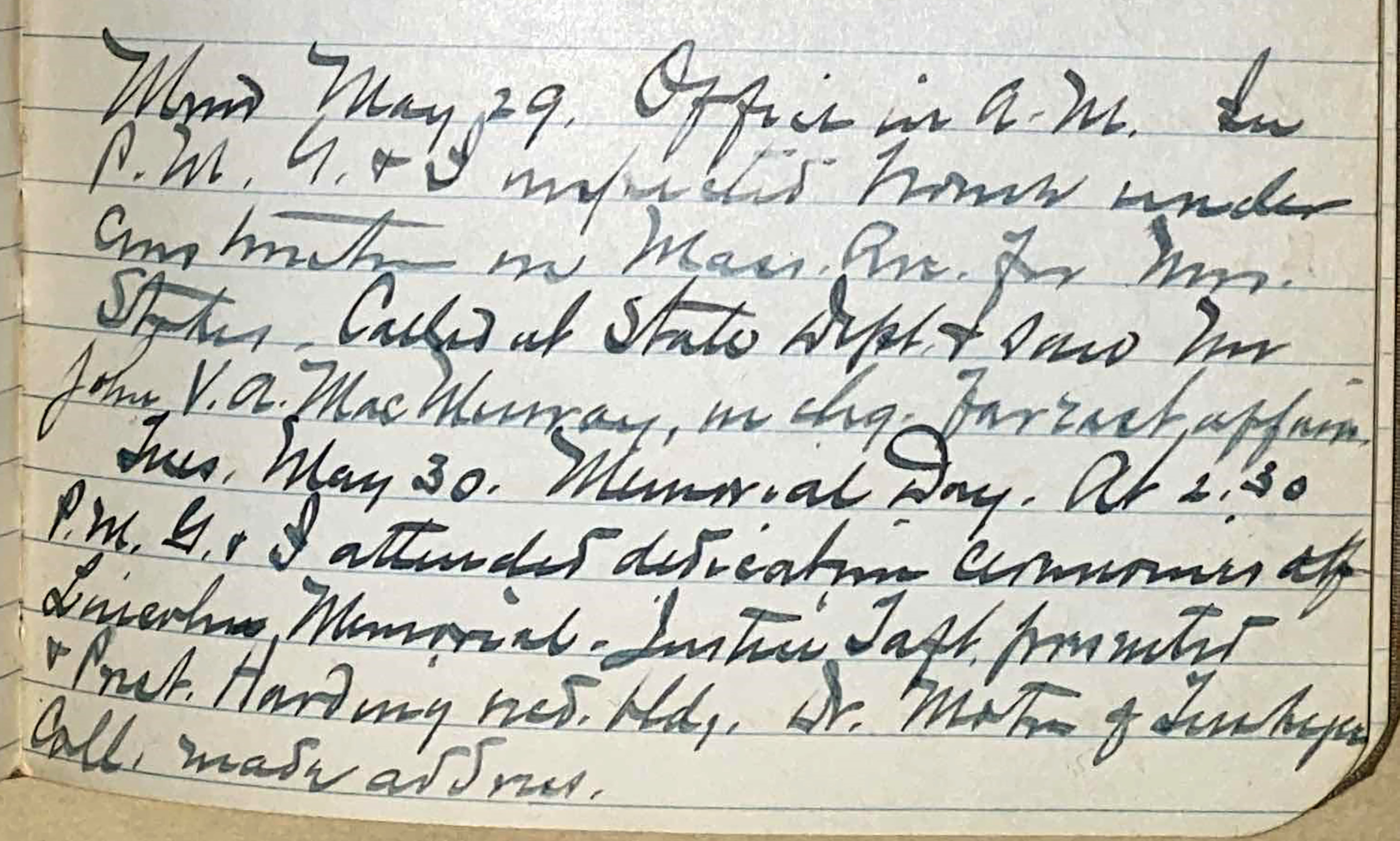

Dedication

On May 30, 1922, tens of thousands witnessed the dedication of the Lincoln Memorial, with Robert T. Lincoln, son of the president, attending. Robert R. Moton of Tuskegee Institute made an address. Sherrill, under the direction of the LMC, had helped arrange the ceremonies. In the months following, as chief of OPBG, he advocated for supplementary funds for lighting and for additional watchmen and their uniforms.

Over the next ten years, Army Engineer officers in the OPBG continued to manage federal lands and monuments in D.C. In 1933, the president disbanded the office and transferred most of its functions to the National Park Service, but the Army Engineers and the OPBG will be forever linked to the early history of the Lincoln Memorial.

In the years since its dedication, the Lincoln Memorial has often served as the site of noteworthy and emotional moments in U.S. history, including protests and celebrations, especially those related to civil rights. On the front steps on Easter Sunday 1939, African American opera singer Marian Anderson performed to an audience of 75,000 after the Daughters of the American Revolution would not let her sing at Constitution Hall. Of the event, historian Harold Holzer remarked that, “Suddenly this statue and this building became a symbol of aspirational equality, instead of just a symbol of Northern and Southern brotherhood.”[1] Indeed, only 24 years later, the memorial was the setting for one of the biggest moments of the civil rights movement, when Dr. Martin Luther King gave his famous “I Have a Dream” speech to an enormous crowd in 1963. Countless events have taken place at the memorial before and since, as the statue of Lincoln looks out from its temple.

|

|

|

Former Chief of Engineers Maj. Gen. William M. Black attended the ceremony and noted it in his diary. The entry reads: “Tues. May 30. Memorial Day. At 2.30 P.M. G & I attended dedication ceremonies of the Lincoln Memorial. Justice Taft presented & Pres. Harding recd. bldg. Dr. Moton of Tuskegee Coll. made address.”

Office of History, William Black Collection

|

The completed memorial, ca. 1940s.

Office of History

|

[1] https://www.washingtonpost.com/history/2022/05/28/lincoln-memorial-dedicated-100-years/

May 2022.

No. 152.