Over ten days in the spring of 1945, Army Engineers expedited the invasion of Germany and thus shortened the Second World War in Europe by daringly capturing one of the last bridges left standing across the River Rhine. It had been nine months since D-Day, and Allied forces had fought in several long, difficult campaigns across France and the highlands of the Ardennes forest and had just crossed the German border. The last natural barrier to driving deeper into German territory was the Rhine. Starting in March, Operation Lumberjack, led by the U.S. First Army, aimed to secure the west bank of the river and prepare for a massive crossing to be led by the British. In order to undermine German supply lines to the front, the Allies had systematically bombed bridges up and down the river for months, so the discovery of an intact WWI-era bridge across the Rhine at the town of Remagen (about 14 miles south of Bonn) was a big surprise.

Brig. Gen. William M. Hoge, an engineer soldier, was in charge of Combat Command B, 9th Armored Division, when its leading elements discovered the Ludendorff rail bridge still standing at Remagen. “I got up to the Rhine and stood there on the bank and looked down, and there it was,” Hoge recalled. “The bridge was there right above the town. I couldn’t believe it was true. I issued an order right away to go down and grab that bridge, go down through the town and put tanks on both sides of the bridge, firing parallel to it.” The risk was exceptional—what if the Germans destroyed the bridge while Hoge’s forces were crossing it or even allowed some to cross before cutting off their retreat?

His superiors had tasked Hoge to proceed south down the Rhine, but he disregarded those orders on seeing the bridge standing. “I knew it was, well, a dangerous thing, unheard of; but I just had the feeling that here was the opportunity of a lifetime and it must be grasped immediately,” remembered Hoge. “It couldn’t wait. If you had waited, the opportunity [would be] gone. That was probably the greatest turning point in my whole career as a soldier—to capture Remagen.”

|

|

|

|

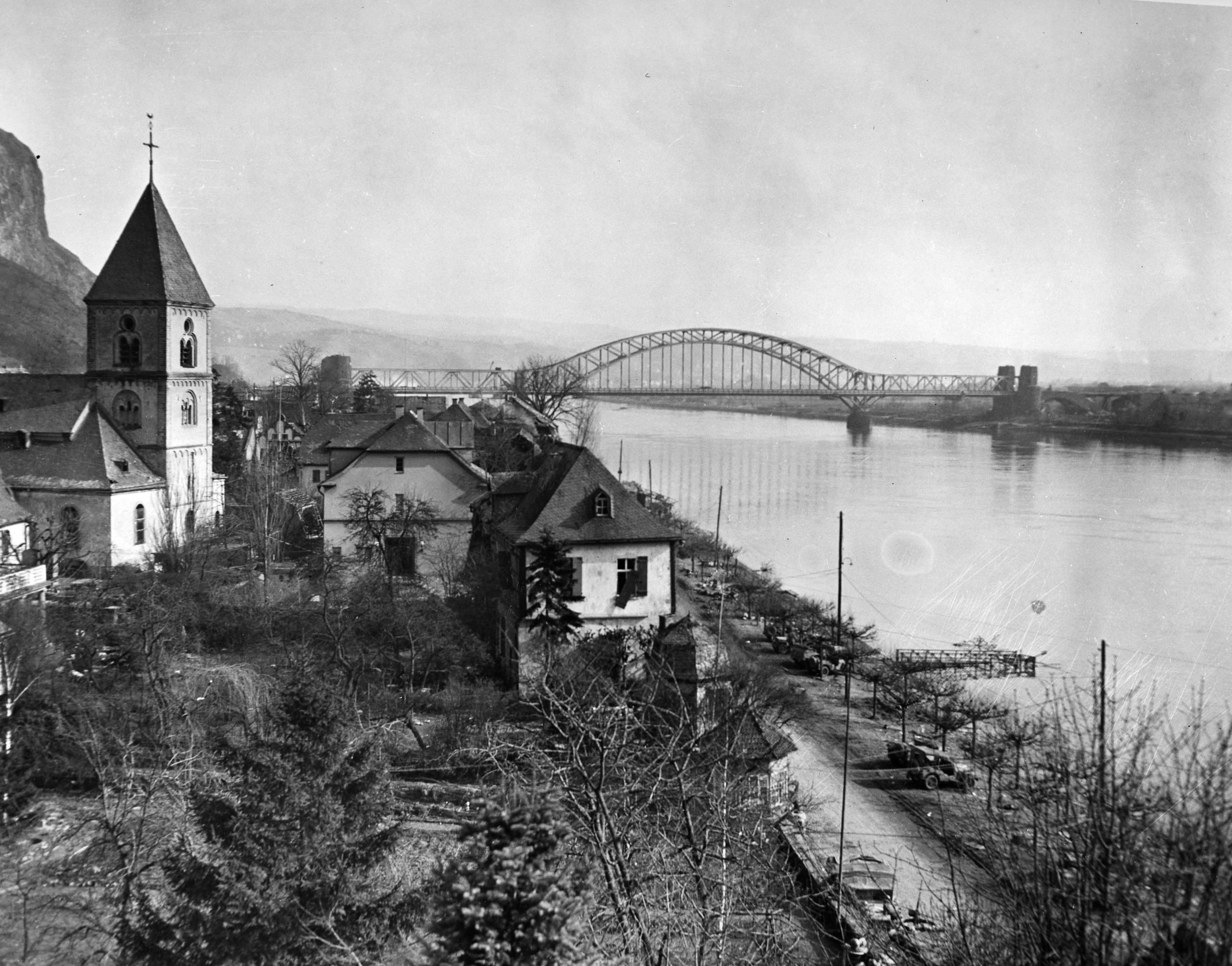

The Ludendorff Bridge at Remagen, Germany. CEHO

|

Brig. Gen. William M. Hoge, 9th Armored Division. CEHO

|

Personnel preparing a recording for broadcast after the bridge’s capture. CEHO

|

| |

|

|

Combat Command B captured the town on the west side of the Ludendorff Bridge on March 7. After witnessing German explosive charges going off but failing to destroy the bridge, Hoge’s engineers quickly started cutting wires and removing a thousand pounds of unexploded demolitions while German artillery on top of the hills on the east side of the river kept up a steady bombardment of American positions around Remagen and the bridge itself. Engineers then started repairing the bridge’s railway and planking so that tanks could move across. Running to avoid sniper fire, an infantry battalion quickly crossed the river and started establishing a bridgehead on the east side, at the edge of the German industrial heartland. They were followed by the 27th Armored Infantry Regiment, as defending the bridgehead became the top priority for the First Army’s III Corps. Late that night a tank company tested the structure, their first nine Shermans moving carefully across the bridge, “accompanied by an ominous and nerve-wracking creaking.” For the next several days, the bridge remained essentially a precarious, one-way street deeper into Germany as Hoge directed a steady stream of soldiers, supplies, and equipment across the river.

|

|

|

| Engineers of the 164th Engineer Battalion construct pontoons and anchors for temporary bridge. CEHO |

|

276th Combat Engineer Battalion put down rails across the Ludendorff Bridge. Four hours after this image was taken, the bridge collapsed. National Archives |

| |

|

|

Meanwhile, infantry units and engineers, with the support of landing craft acting as ferries, worked rapidly under constant enemy fire to build alternate crossings near the Ludendorff Bridge site, including a steel treadway bridge and a heavy, reinforced pontoon bridge upstream. The fast-moving Rhine, with its gravelly bottom, required engineers to fabricate special anchors to hold in place the temporary bridges and the logs and nets used to protect them from mines and enemy swimmers. Lt. Col. H. F. Cameron commanded the 164th Engineer Battalion, which was in charge of river protection at Remagen. “We put the first nets across and they started creeping. We almost lost a bridge of our own stuff, but we got it out of the way,” Cameron remembered. “So we figured there was only one way to anchor our net and prevent creeping. We took four Bailey panels, welded them together, and then lined them with reinforcing steel wire...and then filled boxes with rock. Well, with the four Bailey panels at 580 pounds a panel, filled with rock, we figured there were six or eight tons in each one of those anchors.”

Over the next ten days, the Germans made several concerted efforts to destroy the temporary bridges and the Ludendorff Bridge itself. These attempts included shooting out the floats from under the treadway bridge, numerous air raids, and even launching V2 rockets from the Netherlands—the only time the missiles were fired at a tactical target in Germany during the war. They also sent floating mines, explosive-laden barges, and even special operations swimmers down the river. In response to the aerial bombardment, the Americans installed hundreds of anti-aircraft weapons to protect the bridgehead. American tank companies also deployed a new technology at the bridge that had been developed secretly—powerful searchlights capable of throwing off enemy targeting while illuminating much of the river valley to enable work at night.

|

|

Collapsed Ludendorff Bridge, 17 March 1945. CEHO

|

| |

On March 17 the Ludendorff Bridge finally collapsed while two hundred soldiers from the 276th Engineer Combat Battalion and 1058th Engineer Port Construction and Repair Group were still desperately working to maintain it. The bridge collapse ultimately killed twenty-eight soldiers and injured sixty-three others; of those who died that day, eighteen were missing and likely drowned in the swift-moving river. By that time, however, the Allies had gained a true foothold deep in German territory. Because of the early and successful efforts to capture and repair the bridge, five American divisions were able to cross the Rhine in support of Operation Plunder, the large-scale British push across the river farther north in late March. The audacious capture of the bridge at Remagen ensured the success of these operations and shortened the final drive across Germany towards Berlin by weeks, even months.

|

|

|

| The Rhine valley looking south towards the collapsed Ludendorff Bridge. Cameron Collection, CEHO |

|

Wreckage of the Ludendorff Bridge. Cameron Collection, CEHO |

| |

|

|

Quotes from:

Hoge, William M., Engineer Memoirs: General William M. Hoge, U.S. Army. EP 870-1-25 (Washington, DC: Office of History, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, 1993).

H. F. Cameron, Jr. Oral History (1989), HQ USACE, Office of History, Oral History Collection.

***

March 2020. No. 135.