|

| Engineer Henry F. Bamberger was drafted into the U.S. Army in August 1917 and later worked at the Philadelphia District of USACE |

When the great powers of Europe turned arms on one another in the summer of 1914, plunging into what came to be called the Great War, the United States announced it would remain neutral. However, over time, Germany persisted in torpedoing American ships in the Atlantic. That, and the discovery that Germany had made anti-American overtures to Mexico, led the U.S. to declare war on Germany on April 6, 1917, joining Britain, France, Russia, and others. The U.S. declared war on Austria-Hungary, Germany’s ally, in December.

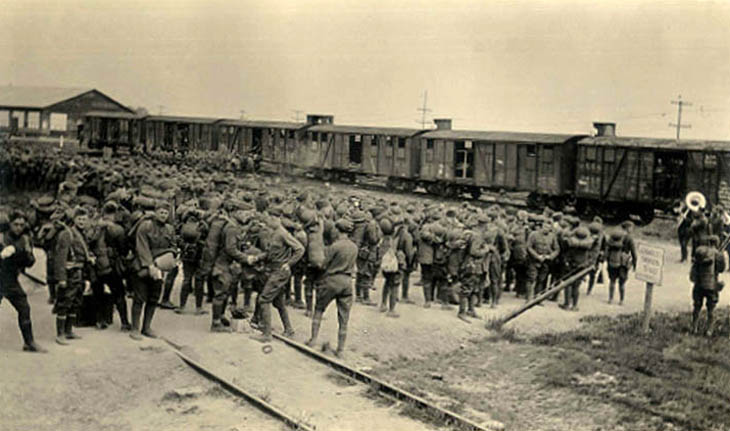

Britain and France, exhausted after three years of war, were in urgent need of manpower, technical support, and supplies. The two allies immediately pressed the U.S. to send engineers. By June 1917 an initial complement of American troops, plucked from duty along the Mexican border, was on its way to Europe as the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF), with Gen. John Pershing in command. By August, nine newly organized engineer railway regiments and the combat engineer regiment of the 1st Division had crossed the Atlantic. Several of the railway units were assigned to British or French formations pending the arrival of more American combat troops. By June 1918, 10,000 American soldiers were arriving in France daily.

The AEF, eventually numbering over two million men, needed to be transported, sheltered, and supplied—a job for the engineers. The hastily organized and trained army engineer regiments were the first to recognize the massive scope of the effort needed to support the AEF, and there was much to learn about the engineering needs of a modern army on a battlefield thousands of miles from home.

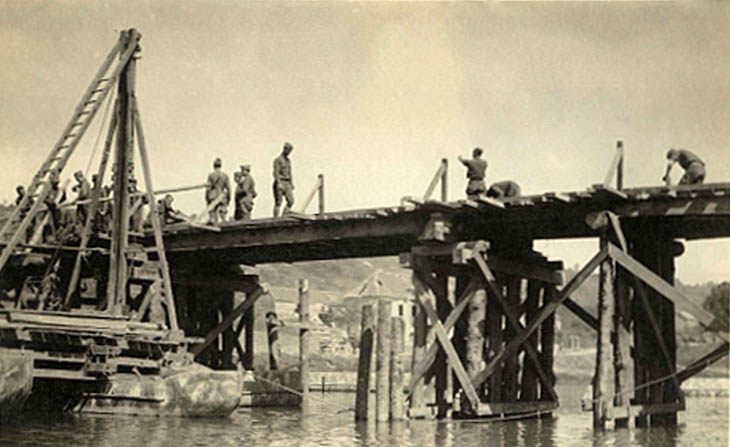

During the war, army engineers built port and railway facilities, roads, and bridges essential to moving troops and war materiel across France. They harvested timber and prepared lumber at 107 sawmills to build docks, storage depots, barracks, and hospitals. They operated searchlights for anti-aircraft defense, produced camouflage materials, and created millions of maps. While many of these activities took place behind the lines, army engineers also engaged in combat along the western front, often fighting as infantry in both defensive and offensive operations. All in all, around 240,000 American army engineers served in Europe during the war, of which approximately 40,000 were African American.

For army engineers, World War I was trial by fire. They had had little experience in mechanized warfare or in supporting a large expeditionary force fighting so far from home. The training manuals of the time described what had to be done but offered little guidance on how to do it, in the worst weather imaginable, and within range of a deadly enemy. So the officers and men of the engineer units learned their trade on the job, and whether they were builders or fighters, the engineers in the Great War met the challenges. They combined courage under fire with critically needed technical skills, and their contribution was essential to the success of the U.S. Army in the First World War.

|

|

|

The 6th Engineers building a wooden bridge

somewhere in Europe |

Soldiers preparing to board trains at Gièvres, France |

Cranes at work in the Army supply depot

at Gièvres, France |

***

April 2017