World War I Corps of Engineers Special Watch to Keep Accurate Time

|

|

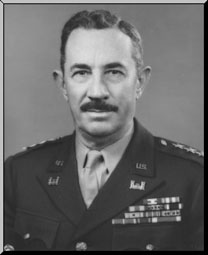

Face and reverse of Lt. Gen.

"Speck" Wheeler's Hamilton watch

|

|

In today’s age of inexpensive yet highly accurate, precision timepieces, it is hard to imagine an era when time was more “flexible.” As society and industry developed, it became more important to keep an accurate measurement of time. Railroad travel was one of the main reasons accurate timekeeping was needed. Poor timekeeping caused the devastating train crash in 1891 that prompted a set of standards for pocket watches used in the railway industry. Henceforth, railway pocket watches were required to be “open faced, size 16 or 18, have a minimum of 17 jewels, adjusted to at least five positions, keep time accurately to within 30 seconds a week, adjusted to temperatures of 34 to 100 degrees F, have a double roller, steel escape wheel, lever set, regulator, winding stem at 12 o'clock, and have bold black Arabic numerals on a white dial, with black hands.”

One of the main American railroad watch manufacturers during that time was the Hamilton Company, located in Lancaster, Pa. Hamilton watches, with their highly regarded 992 and 996 movements, were considered the best watches on the market.

When the United States went to war in 1917, the Army turned to Hamilton for its timekeeping needs. Accurate time was crucial for military operations, and the Hamilton railroad watch became the standard for the American Expeditionary Forces. Approximately 1,000 Hamilton pocket watches were purchased by the Corps of Engineers for the supervision of railroad operations in France. There are five known examples of this Corps watch still around today, according to John Wilterding, Jr., of the National Association of Watch and Clock Collectors.

The USACE museum collection (located at the Humphreys Engineer Center) possesses one such Hamilton pocket watch. Interestingly, it is not marked “Engineer Corps U.S.A.” as directed in the procurement documents. Rather, the dial is simply marked “Hamilton,” like the civilian models. However, the watch is inscribed on the reverse “

4 World War 1917-1919” and includes the engineer castle.

|

Lt. Gen. Raymond A.

Wheeler, also nick-

named "Speck"

|

There is a handwritten note with the watch stating that the 4th Engineers presented the watch to “Speck.” Further research determined that “Speck” was a nickname for Lt. Gen. Raymond A. Wheeler, 36th Chief of Engineers from 1945 to 1949. General Wheeler, then a colonel, was a commander of the divisional 4th engineers during World War I. It is believed that this watch is actually a civilian model rather than a government watch and his regiment probably presented it to him.

Hamilton was not the exclusive source for reliable pocket watches for the Corps of Engineers during World War I. Watches also were purchased from the Swiss companies Ulysse Nardin and Vacheron & Constantin. The USACE museum artifact collection has examples of the Ulysse Nardin military pocket watch and a World War I era Elgin civilian watch carried by an engineer lieutenant.

Even throughout World War II, Hamilton continued to supply the Corps and the military with high quality watches and other instruments, such as naval chronometers.

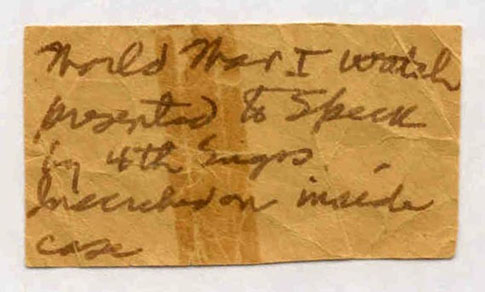

Note accompanying the watch: "World War I watch presented to Speck

by 4th Engrs. Inscribed on inside case."

* * *

January 2003