After World War II, the Corps Formed a New District to Rebuild Greek Infrastructure

When the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers has engaged in major international activities during the post-World War II era, it has used its district organization as a model to manage the work. The approach is firmly grounded on experience. The Corps’ involvement in Greece between 1947 and 1949 set the pattern.

At the end of World War II, Greece stood in virtual ruin. During the German occupation, which lasted until October 1944, the economy nearly collapsed. Allied bombing raids destroyed miles of railroads and devastated the major port cities of Salonika, Volos, and Piraeus. A combination of heavy military traffic and neglect left the country’s highway network in a precarious condition. Then, as the Germans withdrew, they blew up bridges, highways, and portions of the 4-mile-long Corinth Canal, which was a vital link between Athens and the Adriatic Sea.

The threat of civil war and the possibility of a communist takeover convinced President Harry Truman that America had to act quickly. In March 1947, the president asked Congress for $400 million in aid for Greece and Turkey. “It must be the policy of the United States,” he argued in what became known as the Truman Doctrine, “to support free peoples who are resisting attempted subjugation by armed minorities or by outside pressures.”

Congress wasted little time. On May 22, President Truman signed an Interim Aid Bill establishing the American Mission for Aid to Greece (AMAG). Less than a month later, expanding on the principles of the Truman Doctrine, Secretary of State George Marshall proposed his plan for long-term economic recovery for all European nations. By spring 1948, the Marshall Plan was channeling dollars to Europe. Some of the money supplemented AMAG funds for Corps projects already underway.

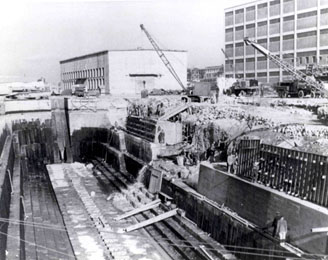

|

| Reconstruction work by Corps engineers in a dry dock at Piraeus Harbor, February 1948 |

To address the immediate crisis in Greece, AMAG planned numerous construction projects to restore the ports and transportation system. The State Department lacked experience in contracting and construction and sought advice from an agency with a proven record in contracting and construction management – the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

AMAG’s Reconstruction Division and the Corps weeded the list of qualified contractors down to 26 but agreed that joint ventures would be the most effective approach. The two organizations cooperated closely during contract negotiations, and contracts were finally awarded to two joint ventures.

When State discovered that these contracts required an extensive construction organization and numerous accountants to provide the required level of oversight, they also tapped the Corps to administer and supervise the contracts.

To manage the construction program, the Corps used its proven district organization, including some seven area offices. The Grecian District, with headquarters in Athens, was organized as part of the North Atlantic Division on August 1, 1947. The district drew personnel largely from existing Corps organizations. Col. David W. Griffiths left his position as Galveston District commander to become the district engineer in Athens.

|

| Col. David W. Griffiths |

District personnel went to work immediately with contractor personnel and the Greek Ministry of Public Works. The contractors successfully recruited Greek nationals but had difficulty attracting American contract supervisors because of the unstable political conditions in Greece. At the peak of the recovery effort, government and contractor forces totaled 629 Americans and 12,131 Greeks.

The reconstruction program initially was scheduled to be completed in one year, and a demobilization plan was in place early; however, guerrilla activity, unusually severe winter weather, and additional new projects resulted in extensions through March 1949.

The Corinth Canal presented one of the greatest challenges. Only 7 kilometers (about 4 miles) in length, the canal could save shippers about 200 kilometers on the trip from eastern to western Greece. Retreating Germans rendered severe damage. Explosions triggered at two points dumped 645,000 cubic meters of earth and rock into the canal. Other debris included a duplex highway-railway bridge, 130 railroad boxcars, six locomotives, mines, and the 3,400-ton steamship Vesta, which had been wrecked and sunk in the canal. Lack of maintenance had affected the entrance breakwaters, and the channel was heavily silted.

The dredge Poseidon (right center) at work clearing the Corinth Canal, 1948

Work to repair the canal began in October 1947. The silt and debris removal effort required special equipment and had to be timed to support the overall excavation schedule. Steers-Grove, one of the two joint ventures, used dredges, floating derricks, tugs, and dump scows in the cleanup effort.

Atkinson-Drake-Park, the other joint venture, undertook road, bridge, and tunnel repair and eventually airfield construction. The highway networks presented a significant challenge. At the end of the war, most major highways were impassable. Ninety percent of the bridges and culverts had been destroyed. Contractors used nearly 30,000 tons of asphalt and more than 650,000 tons of aggregate to restore and surface 1,216 kilometers of highway.

While the engineers’ work was only part of AMAG’s total aid program, it was a most visible part that was appreciated for many years. Once Corps’ contracts were completed, the district organization closed down. Thus the Corps demonstrated very early that it could rapidly put together an effective organization and disband it just as quickly.

* * *

September 2002