An Engineer Helped Save New York City from British Attack during the War of 1812

|

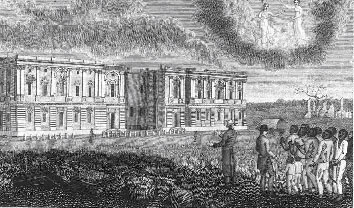

| The British army set fire to the U.S. Capitol, the White House, and the offices of the War and Treasury Departments. Swift later helped to rebuilt the burned capitol. |

Engineers have responded to threats to the security of the United States since the nation's earliest years. Indeed, planning, designing, and constructing seacoast fortifications initially were one of the Corps' primary missions.

From the beginning of the War of 1812, the British threatened the Atlantic coast. British warships captured American ships, blockaded major ports, and raided towns along the coast. Despite stirring victories by the small American Navy, enemy squadrons stepped up their harassment. In 1813 they attacked Norfolk, Virginia, sent troops marauding through nearby Hampton, burned Maryland settlements on the Chesapeake Bay, and landed almost 1,000 men on the North Carolina coast. The next year, British admirals extended their blockade along the entire eastern seaboard and launched amphibious assaults, not only grabbing a large chunk of Maine's territory, but also seizing and burning the White House and U.S. Capitol, and occupying Alexandria, Virginia. Terror gripped the coast.

Recalling its capture by the British during the Revolution, New York, the nation's largest city, felt especially threatened. While British ships cruised just off Sandy Hook, New Yorkers turned to the Army for help. During most of 1813 and 1814, Brigadier General Joseph G. Swift, Chief Engineer of the Army and superintendent at West Point, directed the city's defenses. Until mid-1814, he concentrated on the harbor's permanent forts.

In the summer of 1814, a reinforced British fleet appeared off New York's coast. Fearing an amphibious attack from the north or east, the city's Committee of Defense asked Swift to take charge of emergency preparations. Quickly, he drew up a plan calling for two lines of field fortifications, one stretching along hilltops outside Brooklyn, the other cutting across Manhattan from the mouth of the Harlem River to the Hudson. Then he began to implement the plan and called upon citizens for support. The response was overwhelming.

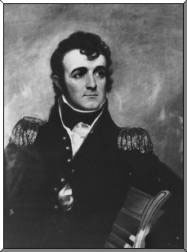

|

| Brig. Gen. Joseph G. Swift |

Between August and November, 38,000 people worked on the defenses. Carpenters and pharmacists, brewers and lawyers, butchers and college students, tailors and artists, free blacks and city officials, rich and poor rubbed shoulders in the trenches, wielding axes, shovels, and spades. Organized in parties of 1,200-2,000, often working from sun to sun, and singing to keep their spirits high, they built two lines of field defenses. Volunteers put in a total of more than 100,000 workdays. People unable to work contributed money, food, tools, and more than 5,000 fascines for the parapets.

Swift oversaw all defense preparations. Before long, he also was plotting strategy, inspecting troops, and directing ordnance, artillery, quartermaster, and medical activities. In the event of a British landing, he intended to lead the main force to repulse them. Impressed by the strength of New York's defenses, the enemy chose easier targets to attack.

In gratitude for Swift's service, the Common Council declared him a benefactor of the city, showered him with gifts, and commissioned John Wesley Jarvis to paint his full-length portrait. After the war, to commemorate the Chief Engineer's heroic effort on their city's behalf, officials hung the painting in New York's City Hall.

* * *

March 2002