|

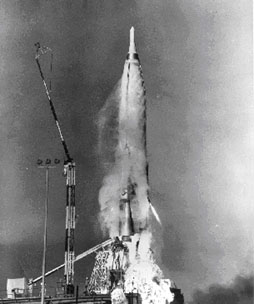

| Atlas test flight, October 1960. The missile was 83 feet tall and when fueled weighed 267,000 pounds. |

In the mid-1950s, the United States and the Soviet Union were locked in a bitter arms race, and both were racing to be the first to deploy a completely new class of weapons: long-range intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs). The Air Force was developing Atlas (SM-65), the United States first ICBM, and in early 1958 it turned to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to build the launch sites for its new missile.

The ICBM was a completely new type of weapon, and when the construction of the first Atlas launch complex began at F.E. Warren Air Force Base in the late summer of 1958, a number of crucial questions remained unanswered. The missile was still under development, and in keeping with the Air Force’s concept of concurrent development, it would take shape at the same time the launch facilities were under construction. In the years that followed, when the Air Force made a design change in the missile, the change frequently forced the Corps to alter the launch facilities. All too often that meant ripping out work and starting over. Moreover, at the outset of the program the Air Force did not know how many Atlas squadrons it would deploy; how the rapidly evolving missile technology would effect the configuration of future launch sites; or how much protection those launch sites needed to offer the missiles.

Eventually the Air Force decided on a national basing strategy, and between 1958 and 1964 the Corps of Engineers built launch facilities for 13 Atlas squadrons. The launch sites spanned the country, from Vandenberg AFB on the Pacific Coast to Plattsburgh AFB in the cool pine forests of upstate New York. The Corps of Engineers’ Ballistic Missile Construction Office (CEBMCO) oversaw the project, and the various Engineer Districts managed the actual construction.

Given the rapidly evolving nature of ballistic missile technology, and the emphasis on getting the missiles operational as quickly as possible (President Eisenhower received weekly briefings on the status of the ICBM program), the Air Force eventually asked the Corps to build three different Atlas launch site configurations. The first launchers were relatively simple aboveground structures; the emphasis was on the ease and speed of construction rather than protection for the missile. As missile technology matured, the later launch sites became progressively more complex, and from the Corps’ perspective, more difficult to build.

The first full Atlas squadrons became operational in 1960. In these so-called "soft" sites, which could only withstand overpressures of 5 pounds per square inch (psi), the Atlas D missiles were stored horizontally within a 103- by 133-foot aboveground launch and service building built of reinforced concrete. The missile bay had a retractable roof. To launch the missile the roof was pulled back, the missile raised to the vertical position, fueled and fired.

The next evolution of Atlas launch sites was the introduction of the "semi-hard" or "coffin" facilities that protected the missiles against overpressures of up to 25 psi. In this arrangement the Atlas E missile, its support facilities, and the launch operations building were housed in reinforced concrete structures that were buried underground; only the roofs protruded above ground level. The missile launch and service building was a 105- by 100-foot structure with a central bay in which the missile was stored horizontally. To fire the missile, the roof was retracted, the missile raised to the vertical launch position, fueled, and then fired.

|

|

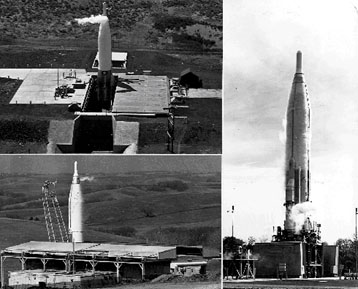

| An Atlas D being removed from its above-ground launcher |

An Atlas E missile towers above its launch facility. The underground launch operations building, marked by two square metal ventilators, is in the foreground. |

|

| The location of 13 Atlas squadrons. The Plattsburgh, NY, facility was the only ICBM site ever built east of the Mississippi River. |

The Atlas F, the most advanced of the Atlas series, was designed to be stored vertically in "hard" or "silo" sites. With the exception of its massive 45-ton doors, the silos, 174-feet deep and 52-feet in diameter, were completely underground. The walls of the silo were built of heavily reinforced concrete. Within the silo the missile and its support system were supported by a steel framework called the crib, which hung from the walls of the silo on four sets of huge springs. During the firing sequence, the missile was fueled, lifted by an elevator to the mouth of the silo, then fired. Although the silo sites were by far the most difficult and expensive Atlas facilities to build, they offered protection from overpressures of up to 100 psi.

For the Corps of Engineers and its contractors, building the launch facilities was tough, demanding, and hazardous work. Despite a rigorous safety program, more than two dozen workmen were killed during the construction process. In the winter, workers in the central plains labored in sub-zero cold, then a few months later, toiled under an unforgiving summer sun. At many sites, contractors worked around the clock. Despite delays caused by flooding, cave-ins, labor unrest, and a nationwide steel strike, the Corps of Engineers completed the last of the 13 Atlas launch sites in 1962.

|

|

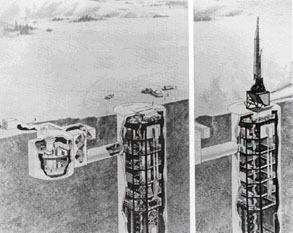

| Atlas launch facilities. Clockwise from lower left: above-ground, horizontal (Atlas D); below-ground, horizontal (Atlas E); and below-ground, vertical (Atlas E). |

Artist's conception of the Atlas F firing sequence.

The firing sequence took 15 minutes. |

The Atlas, however, saw only brief service as an ICBM. Changes in missile technology (most notably the introduction of the solid fuel Minuteman) soon rendered Atlas obsolete, and the Air Force retired its last Atlas squadron by the end of 1965. The launch sites, built with frantic urgency and at great expense, were stripped of their salvageable materials and abandoned.

The last decade has seen a resurgence of interest in the Atlas facilities. In the Midwest, one Atlas D site has been converted into a manufacturing plant for ultralight aircraft, and another hosts high school activities. The Atlas F silos also are being put to work. One flooded silo is used for scuba diving, another has been converted to a luxury apartment with a private airstrip, and a third is being considered for conversion into an ultra-secure computer server operations facility.

Suggestions for Further Reading:

Lonnquest, John C. and David Winkler. To Defend and Deter: The Legacy of the United States Cold War Missile Program. Champaign, IL: USA-CERL Special Report N-97/01, 1996.

Hayes, Thomas J. "ICBM Site Construction." The Military Engineer (November-December 1966): pp. 399-403.

* * *

August 2001