|

| Lt. Col. Joseph Bailey |

In mid-March 1864, a Union force of 42,000 troops and 21 warships began ascending Louisiana’s Red River with the goal of capturing Shreveport, 212 miles upstream. Under the command of Major General Nathaniel P. Banks, the Red River expedition soon ran into difficulties. Banks hoped to transport his supplies and many of his troops by water, but the anticipated spring flood failed to materialize and the water level in the Red River was the lowest in a decade. Moreover, there were few roads in the heavily wooded land adjacent to the river, making the movement of men and materiel difficult.

After a series of sharp engagements, notably the Battle of Sabine Cross Roads on 8 April and another at Pleasant Hill the following day, Banks decided that he could not capture Shreveport within the allotted time, and he ordered his troops to withdraw downriver. However, when the general arrived in Alexandria he found that 10 warships of Rear Admiral David Porter’s Mississippi Squadron, along with 12 transports, were stranded above the city—the river had dropped 6 feet during the previous month, and as a result the ships could not pass over the two sets of rapids above the city.

With his ships bottled up deep in Confederate territory, Porter was in danger of losing much of his fleet. Recognizing the admiral’s plight, Lieutenant Colonel Joseph Bailey, the XIX Corps senior engineer, proposed a daring solution—dam the river to raise the water level, while at the same time concentrating the river’s flow through a narrow sluiceway, thus creating a torrent of water which the warships could ride over the rapids. A former Wisconsin lumberman, Bailey had used a similar tactic for floating logs downstream during periods of low water.

Although Porter later said that Bailey’s plan was a "proposition that looked like madness…," the admiral had few alternatives. At Porter’s request, on 30 April 1864, General Banks ordered his soldiers to work. Working in water that often came up to their necks, over the next week, 3,000 weary soldiers built the dam. In a later report, Bailey described construction of the dam by the lower rapids:

|

|

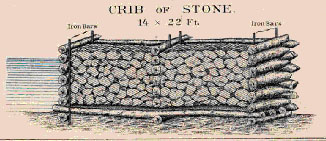

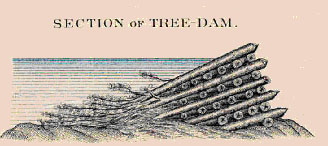

| Drawings of dam sections built on the Red River |

"At this point where the main dam was constructed, the river is 758 feet wide, with from four to six feet of water running at about ten miles per hour.

Two coal barges, 24 X 170 feet were sunk in the channel, having been filled with stone, brick, and iron taken from foundries and sugar mills in the vicinity. Between them was a chute of 66 feet in breadth. From the barges to the right hand bank, the dam was built of cribs of stone; that to the left bank was constructed of trees with their branches entire. The increase of water caused by the main dam was 5 feet 4 inches . . . ."

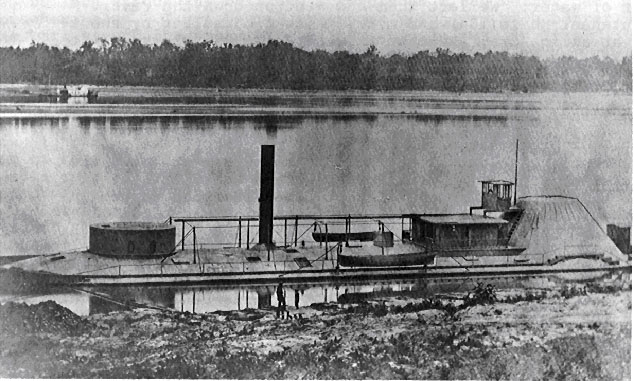

By 8 May the dam had raised the water level enough to send four of the relatively shallow draft gunboats over the rapids. All four made it down, but two scraped hard on the rocks. From that experience it was clear that the water level had to be increased before the deeper draft vessels could pass over the rapids.

Bailey sent the troops to work again, first raising the wings of the original dam, and when that failed to raise the water sufficiently, he ordered the construction of a second dam, a mile upstream, just above the upper rapids. The construction of the second dam was as difficult as the first, but when it was completed it increased the river level by 6.5 feet—enough for all of the warships and transports to navigate the rapids and continue on to the relative safety of the Mississippi River.

|

| The USS Osage, one of the four gunboats that ran the rapids on 8 May 1864 |

|

|

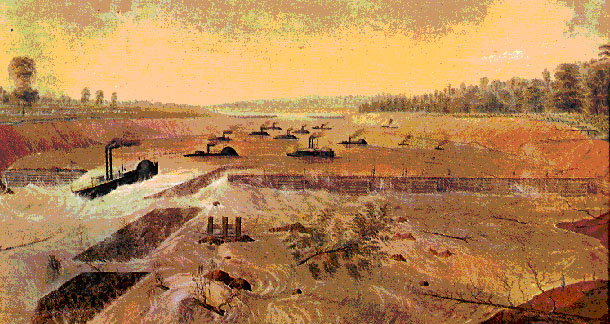

Although not entirely accurate, this painting captures the drama of warships racing through the sluiceway and careening over the rapids. The painting decorated a 3-gallon sterling-silver punchbowl given to Bailey by Admiral Porter and his officers "in commemoration of the safe passage of their vessels." The bowl is now property of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin.

|

For Union forces the Red River campaign was a costly failure. The Army suffered 5,200 casualties and the Navy lost three warships and two auxiliary vessels. The Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War quickly dubbed the campaign the "Red River Disaster."

Despite its criticism of the campaign, Congress singled out Engineer Joseph Bailey for special praise. The Engineer officer received "the thanks of Congress" for his actions, one of only 15 officers so honored during the war. In June 1864, Bailey was given a brevet promotion to brigadier general, and the following April he received another brevet promotion, this time to major general.

* * *

June 2001