|

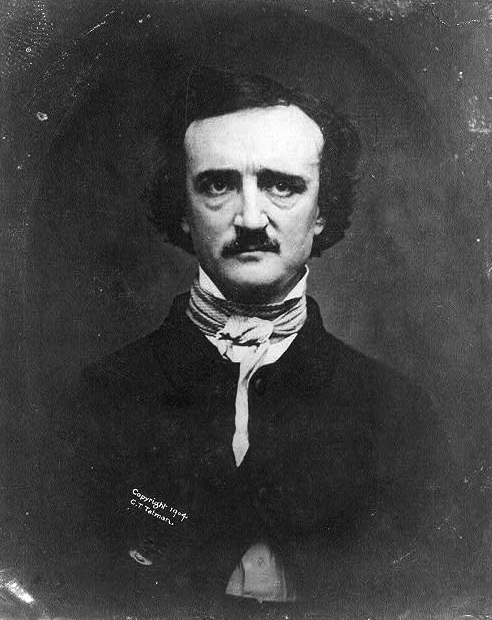

| Edgar Allan Poe |

After accumulating massive gambling debts at the University of Virginia and leaving without a degree, Edgar Allan Poe moved to Boston where, at age 18, he published his first book of verse, Tamerlane and Other Poems, in 1827. It was a slim affair, drew little attention, and made no money at all for its nearly destitute author. Orphaned at an early age, Poe had deeply alienated his wealthy guardian, John Allan, and needed to earn a living. On a whim he enlisted (using an alias, “Edgar A. Perry”) in the Army as a private for a five-year term in the First Regiment of Artillery. Through the fall of 1827 he remained in Boston at Fort Independence but in November relocated to Fort Moultrie, South Carolina. There he prepared shells for artillery and seemed to flourish. Thirteen months later he transferred again, this time to Fortress Monroe at the entrance to Chesapeake Bay. After just two years of military service, Poe attained the rank of Sergeant Major for Artillery, the highest enlisted rank open to him. Then, abruptly, he found a substitute and quit the Army to pursue an appointment to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. Allan intervened on Poe’s behalf one last time and used his considerable influence to secure the appointment.

The 21-year-old poet entered the academy in March 1830. Well-schooled and quick-witted, he excelled at classwork, particularly French. But—despite his experience in the Army—he buckled under the harsh discipline, long marches, and miserable food. “The study requisite is incessant,” he grumbled to Allan, “and the discipline exceedingly rigid.” His keen wit sustained him for a time and, according to his classmate, Thomas Gibson, “poems and squibs of local interest were daily issued [by Poe]… and went the round of the Classes.” One surviving stanza ridiculed the instructor of tactics and inspector of the barracks, Joe Locke, who was tasked also with reporting all cadet violations:

John Locke was a very great name:

Joe Locke was a greater in short;

The former was well known to Fame,

The latter well known to Report.

In January Poe quit his classes with predicable results. He was court-martialed and formally dismissed from the academy on March 6, 1831. As a parting shot, he secured a cadet subscription of $170 to underwrite the publication of his third book of poetry. It was mostly a rehash of his earlier work and was received, as one former roommate remembered, “with a general expression of disgust.” Another wrote in his copy, “This book is a damn cheat,” and that presumably because it contained not one of the humorous squibs and satires that had fed his reputation for genius at the academy. A fair number of cadets flung their copies into the Hudson River.

Poe went on, of course, to become one of America’s most celebrated authors, known particularly for his treatment of mystery, science fiction—and perhaps most famously—the macabre.

|

|

|

|

U.S. Military Academy cadets in the 1860s

|

|

View of West Point from Phillipstown

by W.J. Bennett, 1831

|

All photos courtesy of Library of Congress

***

October 2020