Beginning with the Lewis and Clark Expedition (1804-06) and continuing through the nineteenth century, U.S. Army personnel played a major role in expanding the knowledge of America's natural history. Prominent among them were officers of the Corps of Engineers and the Corps of Topographical Engineers (1838-63). Their contributions included observing, collecting, and writing about the Nation's flora and fauna, especially in the West.

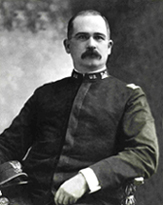

The last of America's notable soldier-naturalists was Thomas Lincoln Casey. Born at West Point in 1857, he was the son of a future Chief of Engineers, also named Thomas Lincoln Casey. The younger Casey graduated from the U.S. Military Academy in 1879 with a commission in the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

Casey's duties took him throughout much of the United States and sometimes beyond its borders. When time permitted he pursued his passion of entomology. He concentrated primarily on the study of the Coleoptera-beetles and weevils. Throughout his thirty-three years of service as an engineer officer, Casey amassed an enormous collection of these insects. In addition to articles in the leading natural history periodicals he produced a series of eleven volumes titled Memoirs on the Coleoptera.

Casey came under fire from other naturalists because of his use of a binocular microscope rather than the hand-held lens then favored by most entomologists. The microscope allowed him to detect minute differences that he believed justified the designation of many new species. He described as new to science an estimated 9,400 beetles and weevils. In the language of biologists, he was a "splitter," that is, one who recognized more species, rather than less as in the case of a "lumper." His critics charged that the distinctions he noted were too minuscule to support the naming of new species. In the end the critics won out; many of the "new" species Casey described are no longer considered valid. But time has vindicated his commitment to the microscope, now regularly used by entomologists.

|

|

Retirement in 1912, with the rank of colonel, allowed Casey to devote much more of his time to scientific research and writing. He and his wife, Laura Welsh Casey (who also collected beetles), kept two apartments in Washington, D.C., one for living, the other for housing his specimens and well-stocked library.

Casey died in 1924; his beloved microscope was buried with him. His widow donated to the Smithsonian Institution's U.S. National Museum approximately 260 boxes containing 116,738 beetles, as well Casey's library. She also established the Thomas Lincoln Casey Fund for the upkeep of his collection and for financing research on the Coleoptera. The Smithsonian's Museum of Natural History now houses the Casey collection.

Although criticized for excessive splitting, Casey is respected as a dedicated collector and researcher. He thought beyond the mere acquisition of specimens and facts, believing that the biological and physical sciences "are all parts of one grand cosmos": "I cannot conceive one of them to be more soul-inspiring than another; they are all equally wonderful, equally beautiful, and equally beyond the ken of finite intellect."

* * *

November 2007