The leaders of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers have gone by various titles, including Principal Engineer, Commandant, and Chief Engineer, until 28 July 1866, when the U.S. Congress designated the commander of the Corps of Engineers as the Chief of Engineers. Of all the leaders of the Corps, only two have received our nation’s highest award, the Medal of Honor. This valorous citation, often incorrectly termed the Congressional Medal of Honor, is awarded by the president of the United States, in the name of Congress, to servicemen who conspicuously distinguish themselves at the risk of their own lives above and beyond the call of duty during combat operations. The genesis of the medal began during the early part of the Civil War, when the U.S. Navy desired to formally recognize individual acts of heroism with a campaign decoration. On 21 December 1861, President Abraham Lincoln signed into law Public Resolution 82 creating a Naval Medal of Valor. Not to be left behind, the War Department wanted an Army counterpart, and on 12 July 1862, Lincoln approved such an award. Within a year, Congress had approved the renamed Medal of Honor as a permanent decoration.

|

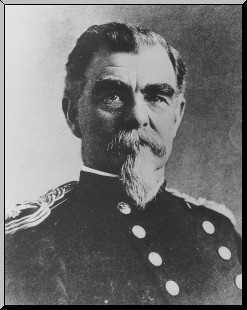

| Brig. Gen. John Moulder Wilson |

John M. Wilson was Chief of Engineers from 1 February 1897 to 30 April 1901. He graduated from the U.S. Military Academy in 1860. Initially commissioned into the Artillery Corps, he later transferred into the Topographical Engineers and then into the Corps of Engineers. His Medal of Honor, issued on 3 July 1897, was awarded for his actions at the Battle of Malvern Hill in 1862. The citation for First Lieutenant Wilson’s award notes that in spite of severe illness he remained on duty on the battle line and continued to participate in the fighting in spite of transfer to a staff position during the campaign. In the post-Civil War period, Wilson worked on various waterways improvement projects. He held positions as West Point’s Superintendent and the Northeast Division Engineer. As Chief, he oversaw the Corps’ contribution to the victorious war against Spain.

|

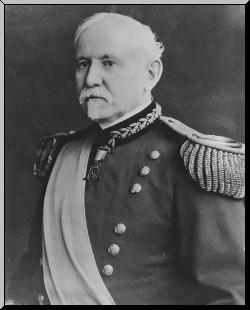

| Brig. Gen. George Gillespie Jr. |

George L. Gillespie, Jr., a native of Tennessee, received a commission into the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers upon his graduation from the U.S. Military Academy in 1862. In spite of his Southern heritage, Gillespie remained loyal to the Union. He received the Medal of Honor for actions associated with the Battle of Cold Harbor when on 31 May 1864, he carried dispatches to and from General Philip Sheridan. In order to ensure that the chain of command’s communications remained intact, Gillespie endured intense enemy fire. He faced enemy capture twice during battle, yet managed to escape on both occasions. Thereafter, he became General Sheridan’s military assistant. Following the war, he worked on port and coastal improvement projects. He also served on the Board of Engineers, as president of the Mississippi River Commission, and as commanding general of the Department of the East. He received an appointment as Chief of Engineers on 3 May 1901, and served until 23 January 1904. For a short time in 1901, he served as Acting Secretary of War. Gillespie was promoted to major general in 1904 and then served as the Army’s Assistant Chief of Staff.

General Gillespie also played a role in the Medal of Honor's alteration to its modern-day form (below). In 1895, Congress had authorized the wearing of a ribbon with the medal, which was approved for the Army version the following year. Gillespie was unsatisfied with this relatively minor change and desired further distinction in the medal's appearance. The War Department approved a new and more ornate version of the medal and Congress approved it on 23 April 1904. General Gillespie obtained a patent for it that fall, and subsequently transferred the patent to the Secretary of War. Other changes to the medal occurred during World War II.

Since 1863, more than 3,400 men and women have received the Medal of Honor, including numerous engineer troops. Combat engineering has been proven essential to modern U.S. military victories and Army engineers have consistently found themselves in harm’s way at the frontlines. The Corps can be proud of its tradition of courage as exemplified by these two leaders who demonstrated the highest values of service and self-sacrifice.

* * *

January 2004