One of the most famous victories in U.S. military history was the successful defense of Little Round Top during the Battle of Gettysburg on July 2, 1863. The events surrounding Little Round Top have been immortalized in histories, novels, and movies, and have been ingrained in the American collective memory. Every year millions of people visit the scene of the battle in Pennsylvania. Little Round Top’s preeminence in American lore, however, cannot be separated from the individuals whose actions made it the subject of legend. One of those individuals was an Army Engineer officer, Brig. Gen. Gouverneur K. Warren, whose quick thinking and determination surely saved the Army’s vital position and made Little Round Top the most famous little hill in America.

One of the most famous victories in U.S. military history was the successful defense of Little Round Top during the Battle of Gettysburg on July 2, 1863. The events surrounding Little Round Top have been immortalized in histories, novels, and movies, and have been ingrained in the American collective memory. Every year millions of people visit the scene of the battle in Pennsylvania. Little Round Top’s preeminence in American lore, however, cannot be separated from the individuals whose actions made it the subject of legend. One of those individuals was an Army Engineer officer, Brig. Gen. Gouverneur K. Warren, whose quick thinking and determination surely saved the Army’s vital position and made Little Round Top the most famous little hill in America.

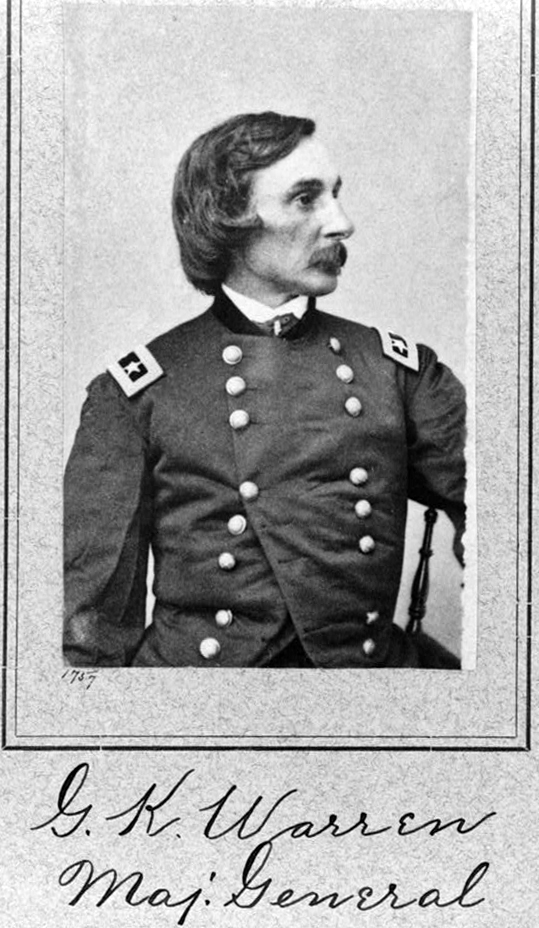

At the time of the Gettysburg Campaign, Warren was the Chief Engineer of the Army of the Potomac. An 1850 graduate of West Point and a Topographical Engineer, Warren had entered volunteer service at the beginning of the Civil War and was ideally suited for such a position. His training in the Corps of Topographical Engineers and his survey assignments in the Black Hills, on the Great Plains, and along the Mississippi River exercised Warren’s keen eye for topography and military applications.

On the first day of fighting at Gettysburg, Warren assisted Maj. Gen. Winfield S. Hancock and Maj. Gen. Oliver O. Howard in establishing the Union position on Cemetery Hill. On the second day, with sunlight fading, Warren received orders that would significantly alter the course of the battle. As he and Army of the Potomac commander Maj. Gen. George C. Meade, also a former Engineer, rode along the Union lines on the afternoon of July 2, they heard gunshots coming from the vicinity of Little Round Top. Meade reacted: “Warren! I hear a little peppering going on in the direction of the little hill off yonder. . . . I wish you would ride over and if anything serious is going on . . . attend to it.”[1]

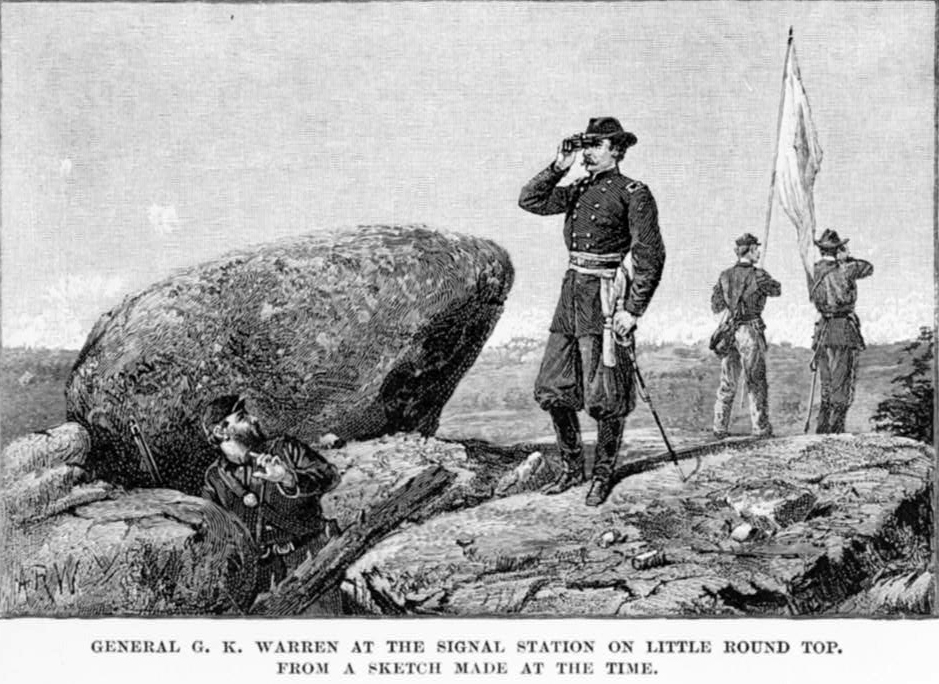

Fighting on the second day began only three hours before dusk, as Confederate forces emerged from their positions to test the left flank of the Federal lines. As Warren neared the hill, having little idea of the enemy’s whereabouts, he was immediately struck by Little Round Top’s importance. It dominated the landscape and overlooked the entire Union army. He realized the summit, occupied only by a signal station with a few soldiers, was “the key of the whole position,” meaning that losing the hill to the enemy would allow Confederate forces to rake the Federals with musket, rifle, and cannon shot and attack them from the side and rear. In that event, Cemetery Ridge would have to be abandoned, leaving the field to confederate commander Robert E. Lee.

Fighting on the second day began only three hours before dusk, as Confederate forces emerged from their positions to test the left flank of the Federal lines. As Warren neared the hill, having little idea of the enemy’s whereabouts, he was immediately struck by Little Round Top’s importance. It dominated the landscape and overlooked the entire Union army. He realized the summit, occupied only by a signal station with a few soldiers, was “the key of the whole position,” meaning that losing the hill to the enemy would allow Confederate forces to rake the Federals with musket, rifle, and cannon shot and attack them from the side and rear. In that event, Cemetery Ridge would have to be abandoned, leaving the field to confederate commander Robert E. Lee.

Warren climbed to the summit of the ridge, and from there he saw the extreme left flank of the Union Army at the bottom of the hill. He also realized that that Confederate army was moving around those soldiers’ flank, shielded by a line of trees. With Little Round Top unmanned, the Confederates would easily be able to conquer it and bewilder the remainder of the Union position.

Warren’s epiphany resulted in immediate action. He sent a courier to General Meade to request an additional division for the defense of the mound. He also appealed for a brigade from the nearby III Corps, eventually answered by Maj. Gen. George Sykes who sent Strong Vincent’s brigade, comprised of the Sixteenth Michigan, Forty-Fourth New York, Eighty-Third Pennsylvania, and Twentieth Maine regiments, to the hill.[2]

Given the importance of the situation, Warren also rode down the back of the hill to commandeer additional troops. By chance, he first ran into soldiers that he had previously commanded. He was therefore easily able to convince Col. Patrick “Paddy” O’Rorke, commander of the 140th New York Infantry, to turn his regiment from its course and up the backside of Little Round Top. Warren escorted O’Rorke’s men, along with Lt. Charles Hazlett’s battery of the Fifth Artillery, up the slope. Because of the rugged and steep nature of the hill, the men had to lift and push the cannons up the slope, and even General Warren helped drag the guns to their placements.

On the top of the hill, Warren and his band of soldiers made an easy target for the Confederates, now surging across the landscape below toward the hill. As the 140th reached the summit and bounded down the other side, Colonel O’Rorke was shot and killed instantly. The 140th continued down the hill and encountered John Bell Hood’s Texans, who had found a weak spot between Vincent’s right flank and the rest of the Union line. O’Rorke’s men suffered heavy casualties, losing over 180 killed or wounded, but they pushed the Confederates back and secured the line. The regiment’s adjunct later estimated that they had come within sixty seconds of losing the crest of the hill.

On the top of the hill, Warren and his band of soldiers made an easy target for the Confederates, now surging across the landscape below toward the hill. As the 140th reached the summit and bounded down the other side, Colonel O’Rorke was shot and killed instantly. The 140th continued down the hill and encountered John Bell Hood’s Texans, who had found a weak spot between Vincent’s right flank and the rest of the Union line. O’Rorke’s men suffered heavy casualties, losing over 180 killed or wounded, but they pushed the Confederates back and secured the line. The regiment’s adjunct later estimated that they had come within sixty seconds of losing the crest of the hill.

Meanwhile, Vincent’s brigade was receiving the brunt of Hood’s attack but repelling surge after surge. Warren remained atop the hill, watching the action, where he was grazed in the throat by a rebel minié ball. Fortunately, the wound was slight. He bound his bloodied neck with his handkerchief and returned to his duties.

For more than an hour, the fighting on the slopes of Little Round Top continued, eventually drawing to a close when Col. Joshua Chamberlain’s 20th Maine, exhausted and out of ammunition, fixed bayonets and forced the bewildered Confederates from the ridge. Vincent, Hazlett, and O’Rorke were all killed, but the Little Round Top, the most crucial point dominating the Union line, remained in Federal hands. As daylight dwindled and the final shots of Gettysburg’s second day rang out, Warren rode back to his commander.

Gouverneur Warren’s insight and immediate action saved Little Round Top, and quite possibly the Union line of battle. Maj. Gen. Abner Doubleday later wrote of Little Round Top: “this eminence . . . was the key of the field, but nothing but Warren’s activity and foresight saved it from falling into the hands of the enemy.” Lee’s military secretary wrote of Warren: “the prompt energy of a single officer, General Warren, chief engineer, rescued Meade’s army from imminent peril.” Finally, ten years after the battle, Brig. Gen. Samuel W. Crawford, a V Corps division commander, wrote to Warren, “Your name ought to be forever connected with the saving of our left, for Round Top was saved by your foresight.”[3]

Gouverneur Warren’s insight and immediate action saved Little Round Top, and quite possibly the Union line of battle. Maj. Gen. Abner Doubleday later wrote of Little Round Top: “this eminence . . . was the key of the field, but nothing but Warren’s activity and foresight saved it from falling into the hands of the enemy.” Lee’s military secretary wrote of Warren: “the prompt energy of a single officer, General Warren, chief engineer, rescued Meade’s army from imminent peril.” Finally, ten years after the battle, Brig. Gen. Samuel W. Crawford, a V Corps division commander, wrote to Warren, “Your name ought to be forever connected with the saving of our left, for Round Top was saved by your foresight.”[3]

Warren was surely aware and proud of his accomplishments, yet he never boasted of his actions. He did not mention saving the Round Top in his diary or letters to his wife, but years later he stated, “there was no merit in my actions except to secure for our army a position if I could, which would prevent our lines from being flanked and this when attacked was but giving an opportunity for a fair fight front to front, and there our opponents did not win”[4]

The day after the successful defense, Warren and his commander witnessed the repulse of Pickett’s charge, which essentially ended the Battle of Gettysburg and destroyed Lee’s ability to mount further assaults. Like General Lee’s “high tide,” the Battle of Gettysburg represented the apogee of Warren’s military career. After the battle, he wrote to his wife, “I believe we have completely beaten Lee and that he has nothing to do but fly to Virginia. We shall be after him.”[5]

1. Harry W. Pfanz.

Gettysburg, The Second Day, 201.

2. Vincent’s brigade was the 3rd Brigade, 1st Division, V Corps, Army of the Potomac.

3. David M. Jordan.

"Happiness is not my Companion," The Life of General G.K. Warren, 95.

4. Ibid, 95.

5. Ibid, 97.