The Corps of Engineers during the American Civil War was shaped profoundly by antebellum military sentiments. Specifically, the American public and political leaders mistrusted large peacetime armies and resisted paying for a standing military force. Instead, the nation relied heavily upon militias and volunteer forces if and when they were needed. The Corps of Engineers, a permanent branch of the Army since Thomas Jefferson’s establishment of West Point in 1802, was continuously hampered by such policies. Although needed to explore the frontiers, protect the borders, build and maintain infrastructure, and manage military education, engineers were few and promotions were glacially slow. In peacetime, these engineers surveyed rivers and the vast American west, built bridges and roads, oversaw lighthouse construction, maintained harbors, and managed the nation’s system of permanent fortifications. In wartime, as West Point’s top graduates, many of the same engineers replaced their survey equipment with side arms and led volunteer infantry on the battlefield. The nation benefitted in wartime from the small enclave’s leadership abilities, professionalism, tactical thinking, expertise in defensive positions, and acute understanding of topographical features. Although not always attached to the agency in times of war, Army engineers displayed their talents regardless of their duties within the military.

The Corps of Engineers during the American Civil War was shaped profoundly by antebellum military sentiments. Specifically, the American public and political leaders mistrusted large peacetime armies and resisted paying for a standing military force. Instead, the nation relied heavily upon militias and volunteer forces if and when they were needed. The Corps of Engineers, a permanent branch of the Army since Thomas Jefferson’s establishment of West Point in 1802, was continuously hampered by such policies. Although needed to explore the frontiers, protect the borders, build and maintain infrastructure, and manage military education, engineers were few and promotions were glacially slow. In peacetime, these engineers surveyed rivers and the vast American west, built bridges and roads, oversaw lighthouse construction, maintained harbors, and managed the nation’s system of permanent fortifications. In wartime, as West Point’s top graduates, many of the same engineers replaced their survey equipment with side arms and led volunteer infantry on the battlefield. The nation benefitted in wartime from the small enclave’s leadership abilities, professionalism, tactical thinking, expertise in defensive positions, and acute understanding of topographical features. Although not always attached to the agency in times of war, Army engineers displayed their talents regardless of their duties within the military.

After the outbreak of the Civil War, many senior engineers temporarily left the agency to accept commissions in the volunteer army raised by the various states. In so doing, they vacated their positions on America’s rivers and harbors to lead regiments, divisions, and even entire armies in America’s bloodiest conflict. Therefore, many of the most recognizable names in American military history rose from and later returned to engineer duty. The parallel systems led to somewhat confusing discrepancies in military rank between regular and volunteer forces. For example, Andrew A. Humphreys was a major in the Regular Army just prior to the war. He accepted a commission and rose to the rank of major general in the Volunteer Forces during the war, and he reverted back to a lieutenant colonel in the Regular Army after its end. Promotion in the Volunteer Forces generally did not affect one’s rank in the Regular Army. In addition to those who left the engineers temporarily, seven resigned their commissions to take up arms for the Confederate States of America and were destined to meet their brethren the battlefield. Others remained with the Corps of Engineers and constructed Washington’s nearly impregnable ring of defenses or threw bridges across rivers for advancing armies. Finally, fourteen engineer officers paid the ultimate sacrifice and perished during the war.

By 1863 the Corps of Engineers had forty-six officer positions, but twenty-six of these officers had left to serve with the Volunteer Forces or on Army staffs, leaving only twenty engineers directly subject to the Chief of Engineers’ orders. One of the most difficult decisions Corps leadership made was whether or not to fill its diminished ranks with civilian engineers, members of other Army branches, or possibly lower-ranking West Point graduates. Chief Engineer Joseph Totten, rather than diminish the quality of his personnel, chose not to accept engineers from non-traditional departments and only increased recruitment from West Point. Throughout the war, those remaining with the agency continued to perform their traditional duties but with greater emphasis on fortifications and defense.

One of the largest and most visible projects undertaken during the Civil War was the multi-fort ring that became known collectively as the Defenses of Washington. These forts and the ring road connecting them were not only conceived to protect the capital from the adjacent Confederate states but they also served as anchors of the grand strategy for the Army in the East. If Washington could be protected by a series of near-impregnable fortifications, then the Union would not have to maintain an army between the capital and the enemy, freeing up many forces for offensive campaigns. Beginning in May of 1861 with the capture of strategic Arlington and Alexandria heights, the engineers began constructing defenses that could, with a small body of defenders, withstand a sizable assault. After only a few weeks of preparation, Brig. Gen. Irvin McDowell led the Army of the Potomac past the capital’s defenses to meet the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia at Manassas Junction. After McDowell’s troops were driven from the field and back to D.C., the engineers’ hastily built and garrisoned fortifications were all that stood between the White House and the Capitol and secessionist forces. Fortunately, Confederate leadership believed the defenses to be too strong to overwhelm and did not pursue. For the remainder of the war, roughly fifteen engineer officers were employed in Washington’s defenses at any given time. By 1862 they had completed thirty-seven forts, and by 1865 the number stood at sixty-eight, all within a thirty-seven-mile perimeter connected by trenches and blockhouses with roads leading back to central locations.

Confederate General Robert E. Lee tested the Union’s strategy and the Defenses of Washington in 1864. Hoping that a raid upon the capital would force Union General Ulysses S. Grant to reassign a large portion of his army to protect the city, Lee sent Lt. Gen. Jubal Early and twenty-thousand men up the Shenandoah Valley, across the Potomac River at Harper’s Ferry, and then through the Maryland countryside toward D.C. Even with only a skeleton defensive force to oppose him, the encounter led Early to view the lines as impregnable. Regardless, on July 12 Early attacked Fort Stevens while President Lincoln observed from its parapets. The connecting roads allowed the defenders to quickly converge at the fort and easily repel the southern assault. Early and Lee succeeded only in giving D.C. residents and officials “a terrible fright,” Grant’s advances went unchecked, and Washington’s defenses would never again be challenged.

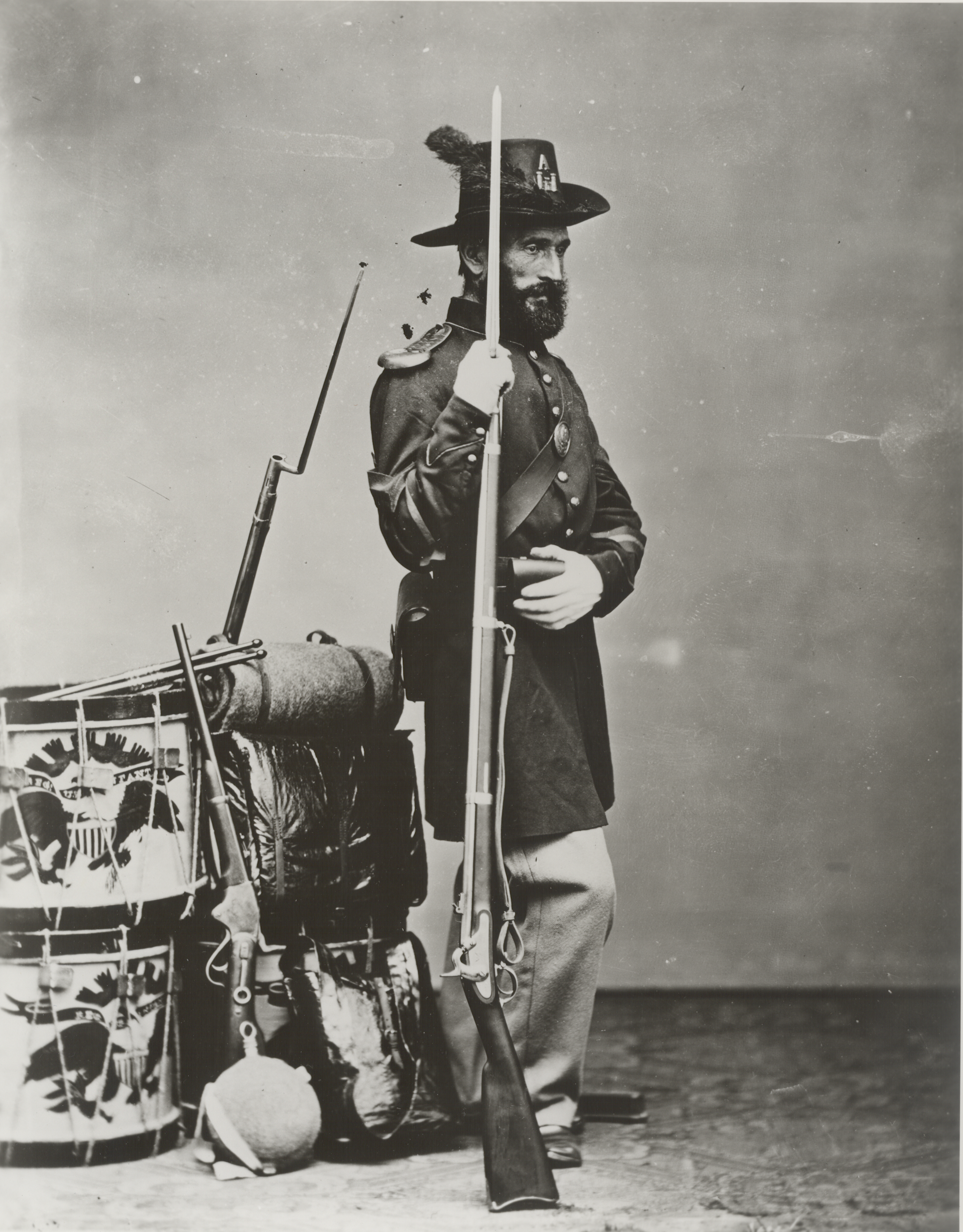

In addition to anchoring the capital’s defense forces, the Corps of Engineers was authorized a battalion of engineer enlistees that it could put on the offensive in the field. Recruited mainly from New England, these engineer volunteers tended to be carpenters, masons, and other skilled workers suitable for engineer duty. The Engineer Battalion consisted of four companies and was attached to the Army of the Potomac from the time of the Peninsular Campaign through the end of the war at Appomattox. Congress had authorized Company A of the battalion prior to the Mexican War; it was ordered to D.C. following Lincoln’s election to protect government buildings and safeguard the inauguration. At the war’s outset, Congress authorized three more companies—twenty-seven fewer than Chief Engineer Totten requested. As a result, the Army suffered a severe shortage of regular engineers throughout the war. By December 1861 the battalion had recruited enough engineers to send to West Point, where the trainees learned traditional sapping and mining techniques and how to fashion field defenses. Then they moved to D.C. to drill with Sgt. Frederick W. Gerber alongside the 15th and 50th New York Volunteer Engineers on bridge building. By late February 1862 they had organized ponton bridge trains and had constructed the first ponton bridge for military service in the United States—an 841-foot span at Harper’s Ferry using 41 pontons to put Maj. Gen. George McClellan’s troops across the Potomac. During the war, six different officers of the Corps of Engineers led the brigade and twenty others served within its ranks. The battalion was most noted for its bridge-building, but they also laid siege to Confederate works at Yorktown, served as infantry at Malvern Hill and Wilderness, and designed twenty-five miles of entrenchments around Lee’s position at Petersburg. The strength of those field works was so great as to prevent Lee from making any assaults on them and ultimately forced Lee to flee, only to be surrounded at Appomattox Courthouse. After Lee’s surrender, the Engineer Battalion marched in a victory parade through Washington, D.C., bringing along with them two of their now-famous pontons.

Ultimately, despite their incredibly low numbers throughout the war, Army Engineers played a pivotal role in the eastern theater. The Engineer Brigade carried the Army of the Potomac across rivers and streams from the Potomac to the James, laid siege to Confederate fortifications, and designed earthworks that protected the Army during prolonged engagements. To a lesser extent, the engineers developed and deployed reconnaissance measures like hydrogen balloons, from which they could map and survey battlefields. And, when necessary, they served as skirmishers and guarded their bridges in the face of enemy assaults. Around Washington, D.C., engineer officers surveyed, designed, and managed the massive system of defenses to protect Washington from enemy attack. By design, the strong defenses effectively freed up Union forces for offensive maneuvers by rendering unnecessary a massive troop presence around the capital. Those engineers officers not involved with the Defenses of Washington were generally on fortification duty elsewhere, ensuring that America’s borders were well-protected in the event of invasion from Confederate-sympathizing European nations. Finally, other officers took leave from the agency to serve as engineer aids to field armies or to lead troops themselves. Famous names like George Meade, George McClellan, Andrew Humphreys, Robert E. Lee, P.G.T. Beauregard, and Gouverneur Warren were Army Engineers for most of their adult lives. Trained at West Point in engineering and the art of war, they had a tremendous impact on how the American Civil War unfolded. Throughout the 150th anniversary period, the Office of History will highlight the individual contributions of select engineer officers and post biographies on this site.

Ultimately, despite their incredibly low numbers throughout the war, Army Engineers played a pivotal role in the eastern theater. The Engineer Brigade carried the Army of the Potomac across rivers and streams from the Potomac to the James, laid siege to Confederate fortifications, and designed earthworks that protected the Army during prolonged engagements. To a lesser extent, the engineers developed and deployed reconnaissance measures like hydrogen balloons, from which they could map and survey battlefields. And, when necessary, they served as skirmishers and guarded their bridges in the face of enemy assaults. Around Washington, D.C., engineer officers surveyed, designed, and managed the massive system of defenses to protect Washington from enemy attack. By design, the strong defenses effectively freed up Union forces for offensive maneuvers by rendering unnecessary a massive troop presence around the capital. Those engineers officers not involved with the Defenses of Washington were generally on fortification duty elsewhere, ensuring that America’s borders were well-protected in the event of invasion from Confederate-sympathizing European nations. Finally, other officers took leave from the agency to serve as engineer aids to field armies or to lead troops themselves. Famous names like George Meade, George McClellan, Andrew Humphreys, Robert E. Lee, P.G.T. Beauregard, and Gouverneur Warren were Army Engineers for most of their adult lives. Trained at West Point in engineering and the art of war, they had a tremendous impact on how the American Civil War unfolded. Throughout the 150th anniversary period, the Office of History will highlight the individual contributions of select engineer officers and post biographies on this site.