George McClellan was born in Philadelphia, the son of an eminent surgeon. After two years at the University of Pennsylvania, he entered the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. Finishing second in the class of 1846, he was commissioned in the Corps of Engineers as a brevet second lieutenant. He distinguished himself in the Mexican-American War, winning brevets to first lieutenant and captain.

George McClellan was born in Philadelphia, the son of an eminent surgeon. After two years at the University of Pennsylvania, he entered the U.S. Military Academy at West Point. Finishing second in the class of 1846, he was commissioned in the Corps of Engineers as a brevet second lieutenant. He distinguished himself in the Mexican-American War, winning brevets to first lieutenant and captain.

After the war he served as an instructor at West Point. Next he participated in a survey of the Red River and in the Pacific Railroad Survey in the Northwest, which explored the county between St. Paul and Puget Sound and between the 47th and 49th parallels. His principal responsibility was to examine mountain passes. Other engineering activity included overseeing the construction at Fort Delaware. In 1854 he became a captain of cavalry, and soon thereafter he traveled to Europe as one of three officers sent to observe the Crimean War. Upon his return he wrote a report on the armies of Europe. He also published a translation of a French manual on bayonet exercises, wrote a work on cavalry tactics, and designed the famous McClellan saddle. In 1857 he resigned his commission and went on to hold executive positions in a number of railroads.

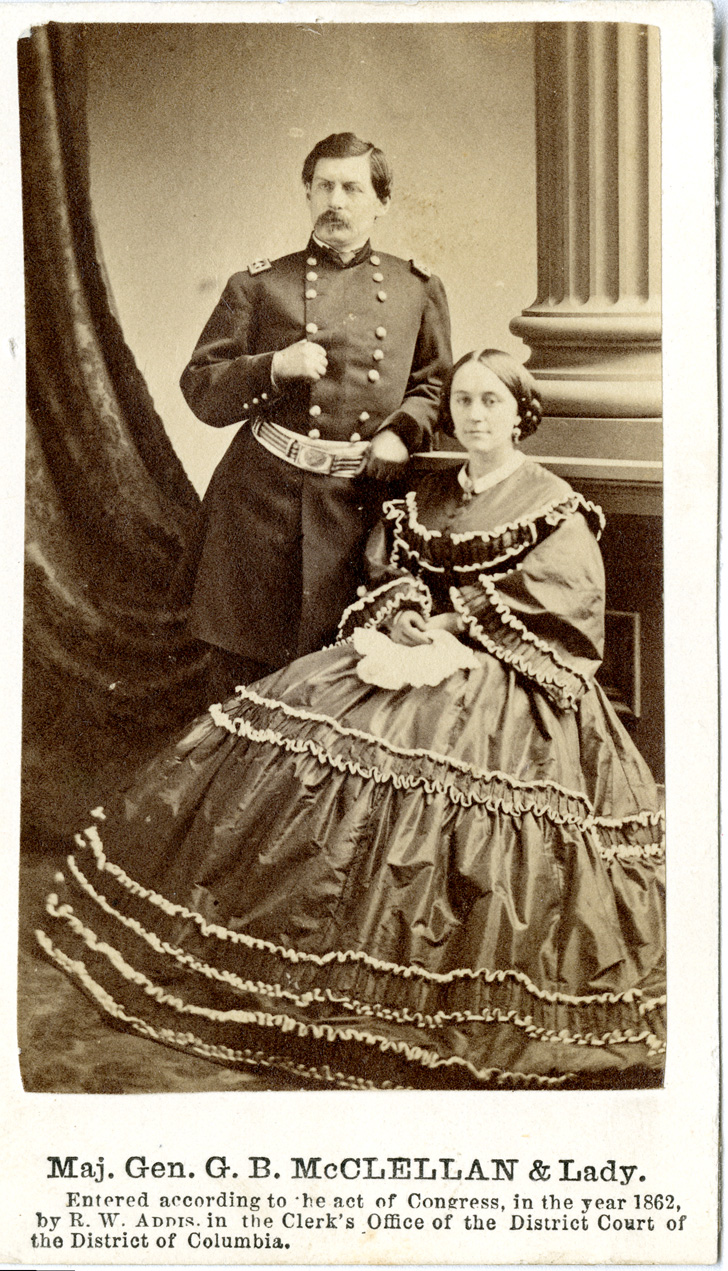

With the advent of the Civil War, McClellan became a major general in the Ohio militia. Winfield Scott, commander of the Union armies, had been impressed with McClellan’s performance in the Mexican-American War and saw to it that the young officer was appointed a major general in command of the United States Army’s Department of the Ohio. Victories over the Confederate forces in western Virginia, for which he received largely undeserved credit, established his reputation as the “Young Napoleon.” At age thirty-four he briefly replaced the aging Scott as general-in-chief.

As a commander, McClellan’s chief contribution to the Union cause was his brilliant ability to organize and train troops. Otherwise, he proved to be a cautious and indecisive leader. He repaid President Lincoln’s patience with him with disrespect. In command of the Army of the Potomac, McClellan belatedly mounted the Peninsula Campaign, the object of which was the capture of the Confederate capital at Richmond. His dilatory movement and belief that the numerically inferior Confederate force was larger than his own condemned the operation to failure. As he was to do repeatedly throughout his Civil War career, “Little Mac” blamed the administration for not yielding to his demands for more soldiers and supplies.

McClellan’s only major battlefield success (albeit a qualified one) was at Antietam, near Sharpsburg, Maryland, in 1862. Despite obtaining a copy of Robert E. Lee’s plans, he again moved slowly and cautiously. The bloody engagement did not result in a decisive defeat of the rebels, but it did check Lee’s northern advance. It was also enough of a victory to motivate Lincoln to issue the Preliminary Emancipation Proclamation. McClellan, who had been returning runaway slaves to their masters, vehemently opposed turning the conflict into a war against slavery.

McClellan’s failure to pursue Lee vigorously finally convinced Lincoln to relieve his arrogant and insubordinate general. Receiving no further assignments, McClellan accepted the Democratic Party’s 1864 nomination for president. His soldiers had adored him, but most of them, as well as the majority of other voters, preferred Lincoln, who won reelection handily.

Following the election he resided in Europe until 1868. Returning to the United States, McClellan found employment in several engineering endeavors. In 1877 he won the governorship of New Jersey. He died in 1885; his self-serving memoirs were published posthumously.

George B. McClellan is one of the most controversial military figures of the Civil War, and his historical reputation is largely negative. To his credit, however, the later Union victories in the eastern theater of the war owed much to his forging of the Army of the Potomac.