The Engineer's War against Japan

|

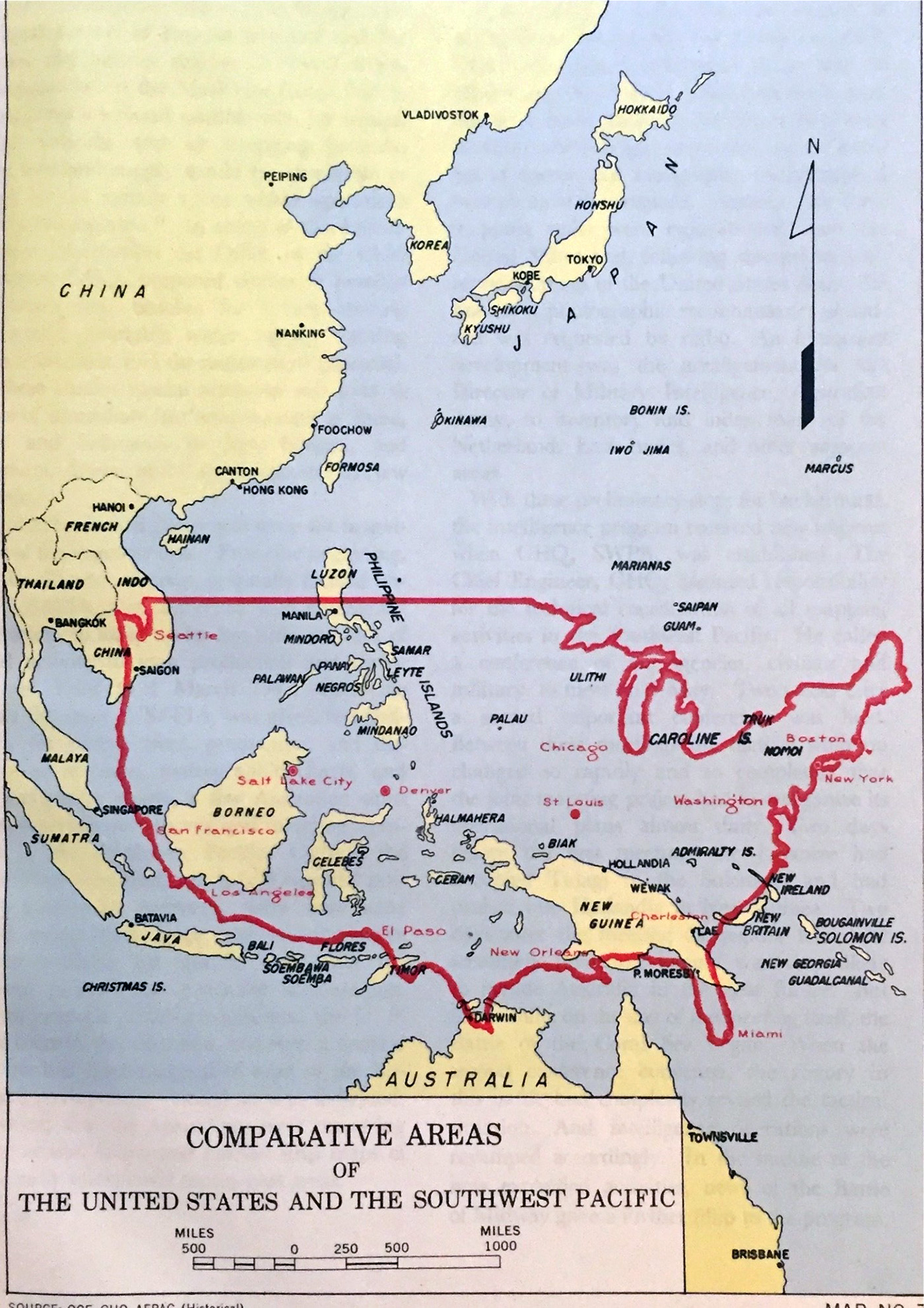

| Map of Southwest Pacific |

| (click to zoom) |

On May 8, 1945, Europe and the United States celebrated Germany’s unconditional surrender on VE Day. Allied forces, however, quickly turned their attention to the Pacific Theater, where months of brutal fighting still lay ahead.

General Douglas MacArthur, Supreme Commander of Allied Forces in the Southwest Pacific Area, stated that the war in the Pacific was an “Engineer’s War.” A host of problems required immediate and unique solutions. From contending with the terrain and climate in both primitive Pacific jungles and frozen northern sites, to conducting nuclear research and engineering stateside under the Manhattan Project, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers’ civilian and military personnel squarely addressed each obstacle presented and played a crucial role in defeating Japan and bringing World War II to an end.

U.S. Army engineers in the Far East and Southwest Pacific toiled in an immense area that is geographically larger than the U.S. and encompasses the icy waters of Alaska, tropical coral atolls, and isolated islands marked with rugged and seemingly insurmountable mountain peaks.

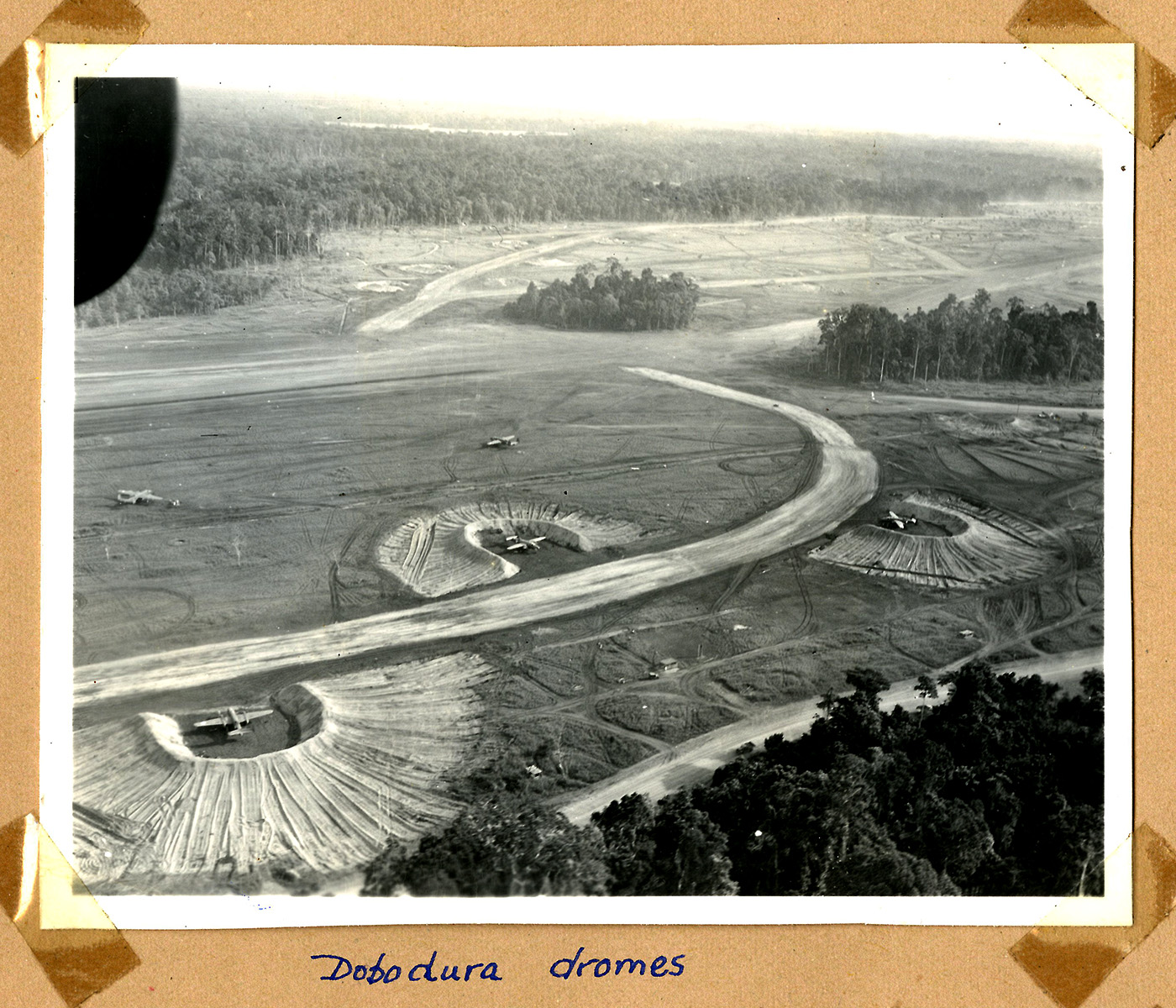

In such environments, engineers built air strips; constructed ports; raised bridging; laid pipelines; dredged rivers and harbors; operated sawmills; photomapped; and completed myriad other tasks in support of Army ground and air forces. Engineers constructed, improved, and maintained 10,000 miles of roads and 300 miles of railroads, including those along the Ledo Road connecting India to China, and erected 3 million square feet of storage facilities on New Guinea. They compiled 1,300 unique maps using aerial photography and constructed hospital facilities with 128,000 beds and installations to support 1.5 million troops. Amphibious engineers participated in 147 assault landings and delivered more than 3 million tons of cargo.

|

|

| Laundry Day at engineer quarters, Aleutian Islands, |

|

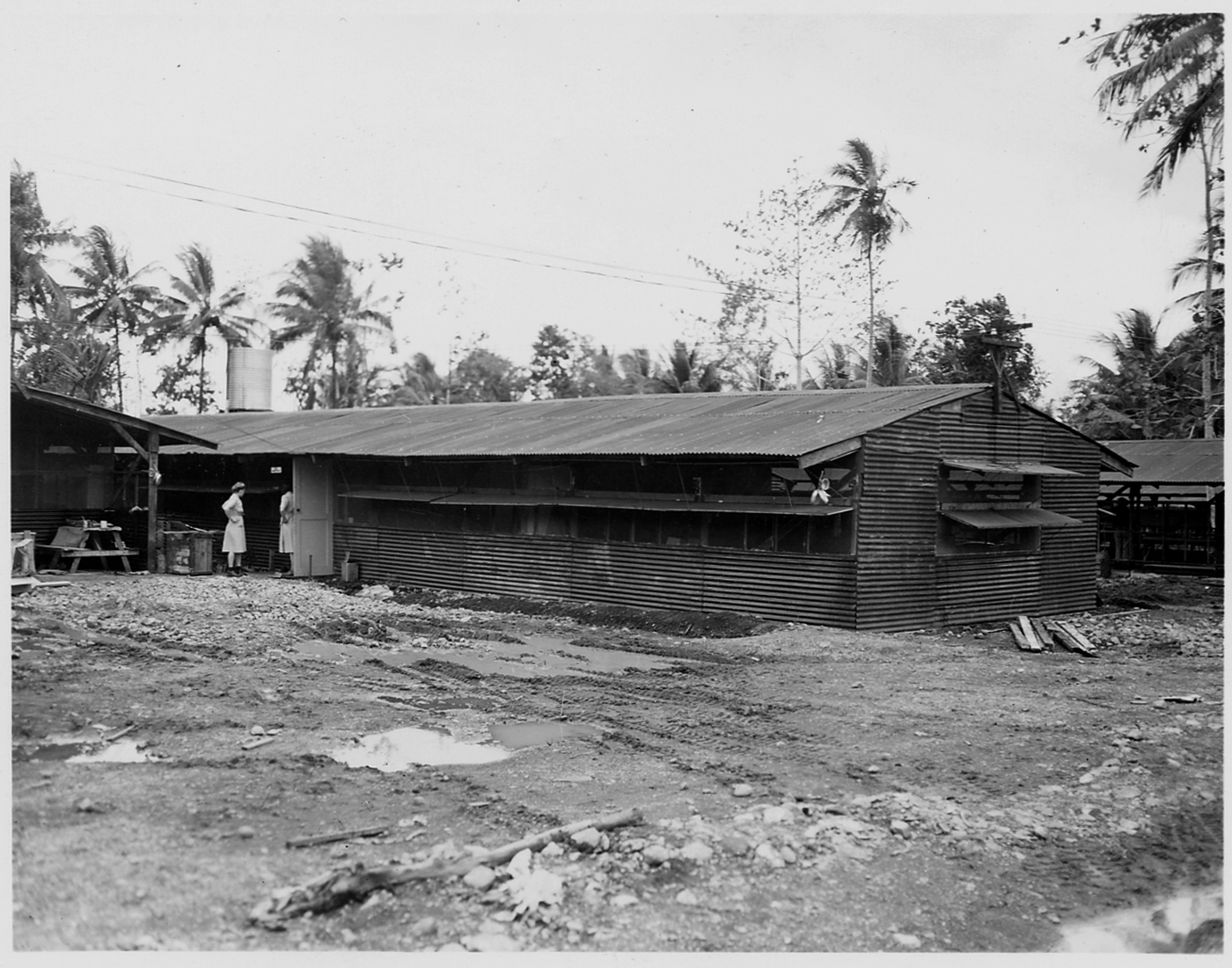

Hospital in New Guinea, ca. 1943. HQUSACE, Office of History.

|

Alaska, ca. 1942. HQUSACE, Office of History. |

By the end of the war, more than 250,000 engineers were engaged in the Southwest Pacific—13 percent of the Army’s total force. Alongside them were local civilians—laborers, painters, plumbers, electricians, blacksmiths, tinsmiths, clerks, and carpenters who assisted with the massive construction program.

By August 1945, Japan’s strategic position had become untenable. After the fall of Okinawa, which was only 300 miles from the Japanese home islands, and the two atomic bombings at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan accepted the Allies’ terms for unconditional surrender on August 15, 1945. By the time the official Japanese surrender took place on the deck of the battleship USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay on September 2, 1945, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers had already turned its attention to meeting the requirements of an occupation army. The first Allied troops arrived in Japan on August 30, and MacArthur was charged with overall responsibility for the occupation. Under his command, the “Engineer’s War” continued, though for more peaceful endeavors that saw to the reconstruction and revitalization of a decimated Japanese mainland.

Photos by MAJ (later LTC) Leonard L. Haseman while serving with the 96th Engineer Regiment

in Hollandia, Dutch New Guinea, ca. 1943. Haseman Personal Papers Collection, HQUSACE, Office of History. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

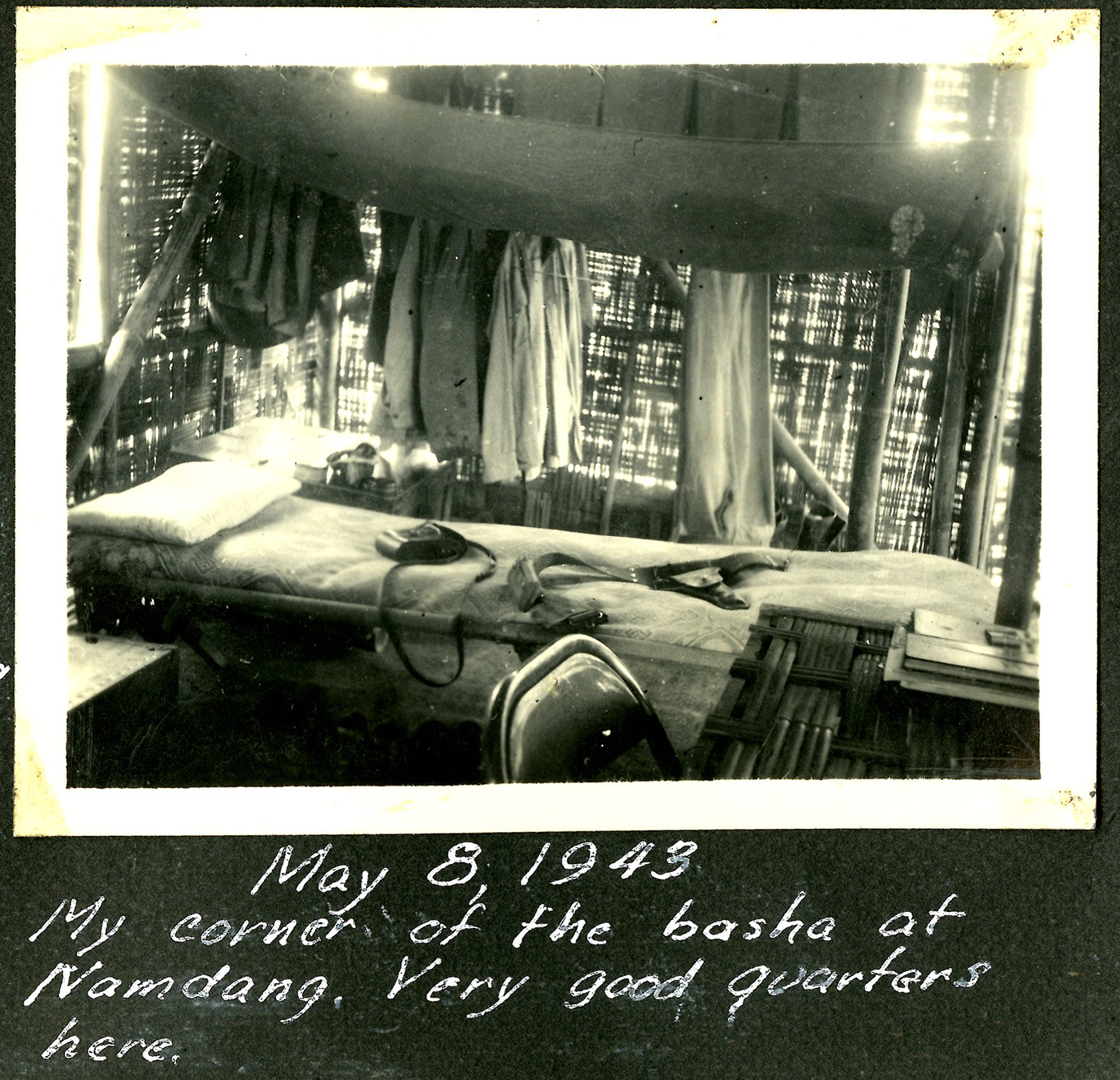

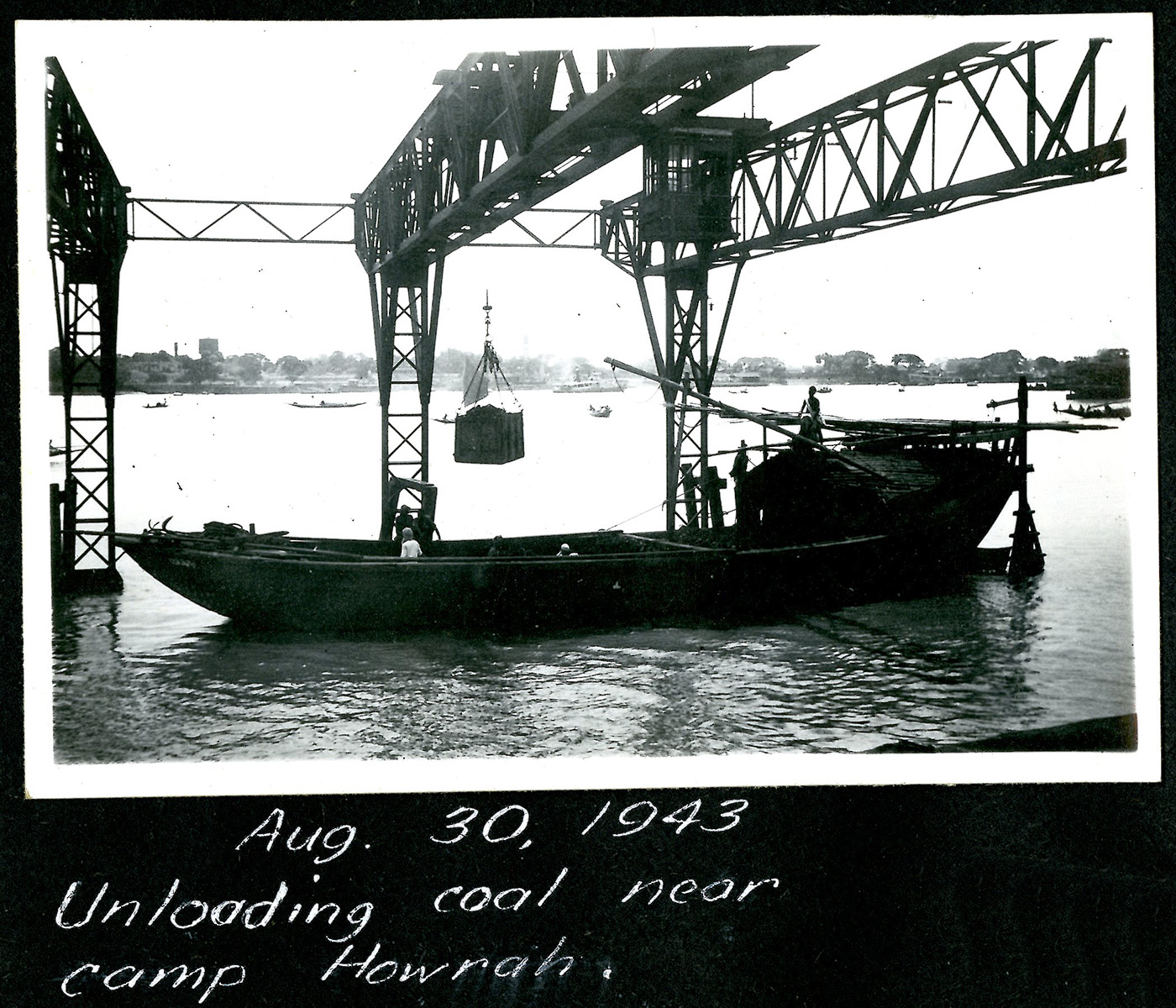

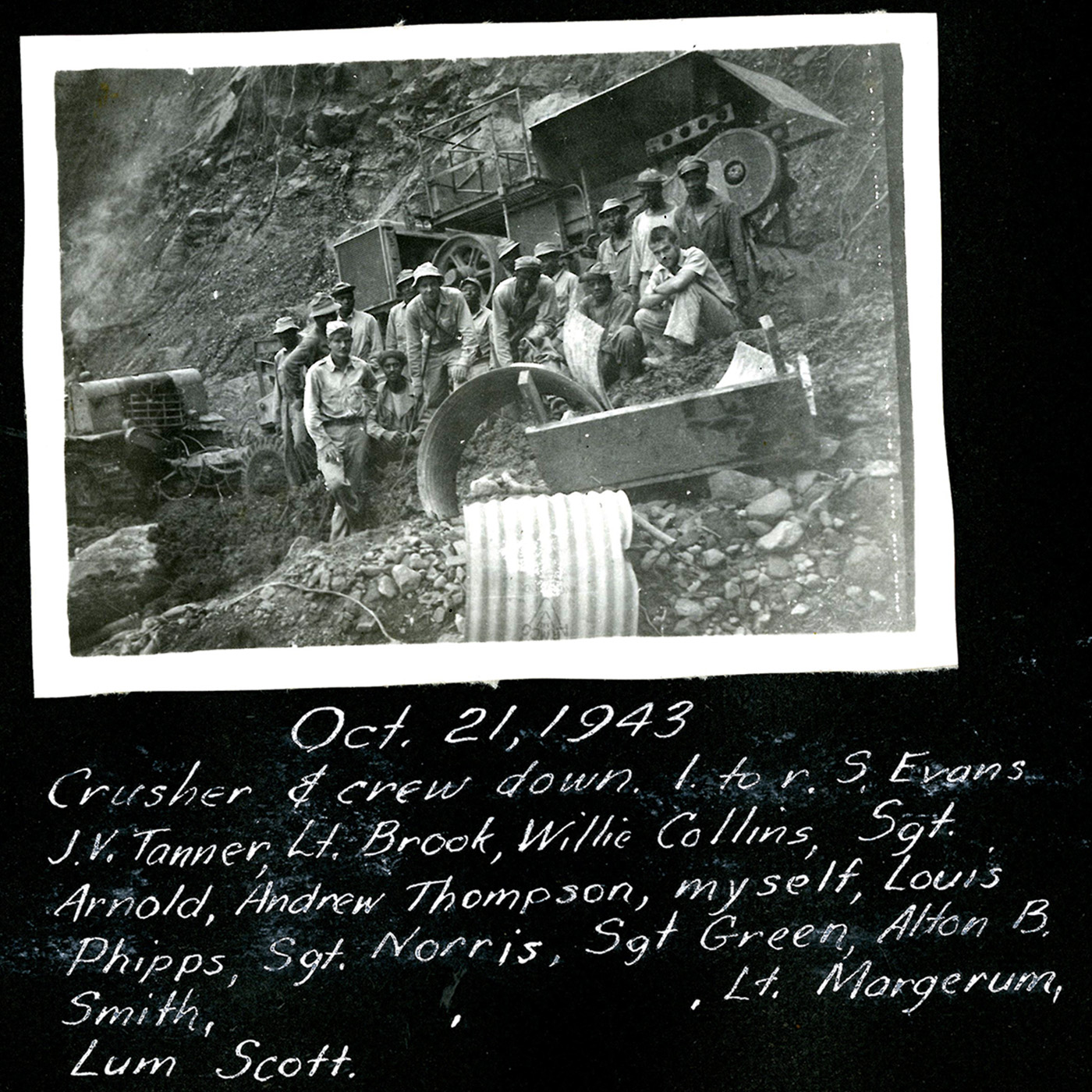

Photos by LT Charles A. Roberts while serving in Burma and India on construction of the Ledo Road

with the 45th Engineer Regiment, 1943. Roberts Personal Papers Collection, HQUSACE, Office of History. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

***

September 2020. No. 138.

Further Reading: