| |

|

|

|

| |

Hired laborers excavating glacial fill by hand at a flood control dam on the Winooski River in Vermont.

Jul. 1933. Office of History |

|

Repairs to a jetty at Sabine Pass near Port Arthur, Texas, by placing a concrete cap. 7 Aug. 1936.

Office of History |

There is nothing new about 21st-century discussions in the United States about federal economic stimulus efforts, recovery acts, and infrastructure programs. In fact, nearly one hundred years ago, the economic crisis that was the Great Depression led to very similar debates and responses from the federal government. The Depression, the most severe and far-reaching economic crisis in the country’s history, was a turning point both for the nation and for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. No previous recession compared to the economic and social turmoil and ruin that took place prior to World War II.

Following a mid-1929 recession and the stock market crash in October, the U.S. economy spiraled into depression and threw more than 15 million Americans out of work. To address the crisis, the federal government under both presidents Herbert Hoover and Franklin D. Roosevelt intervened as never before, taking steps to provide relief and stimulus in a decade-long effort to revitalize the American economy. The Corps of Engineers was well positioned to play a significant role in public relief activities. Its decentralized structure gave it the flexibility and scope to manage projects around the country. Additionally, Congress had just recently tasked the Corps with surveying important American waterways to determine those suitable for potential improvements. These detailed watershed surveys were called 308 reports after the number of the congressional document authorizing them, and by 1934 the Corps had filed more than 150 of the studies, covering such major rivers as the Columbia, Hudson, Sacramento, Potomac, and James. The reports resulted in a roster of prospective Corps projects (and the data and knowledge needed to carry them out) that Congress quickly seized upon to provide rapid and robust unemployment relief—projects that today would be termed “shovel ready.”

Once Congress began enacting and funding economic recovery acts, the Corps of Engineers moved quickly. It continued to fulfill its traditional mission to improve navigation on America’s rivers, harbors, and canals, primarily in the form of single-purpose projects, such as providing a nine-foot navigation channel on the upper Mississippi River. But the Depression also contributed to an evolution in the Corps’ civil works program and the agency overall. This change began with the development and construction of multiple-purpose water resources projects, something the Corps had only just begun to consider in the 1920s. These projects served not only navigation and commerce but also hydropower, irrigation, or water supply. Additionally, the Roosevelt administration embraced these massive projects as an effective New Deal-era jobs program. Construction of the Bonneville and Fort Peck Dams are but two examples of the work originating from the 308 program, and both were projects that employed tens of thousands.

|

|

|

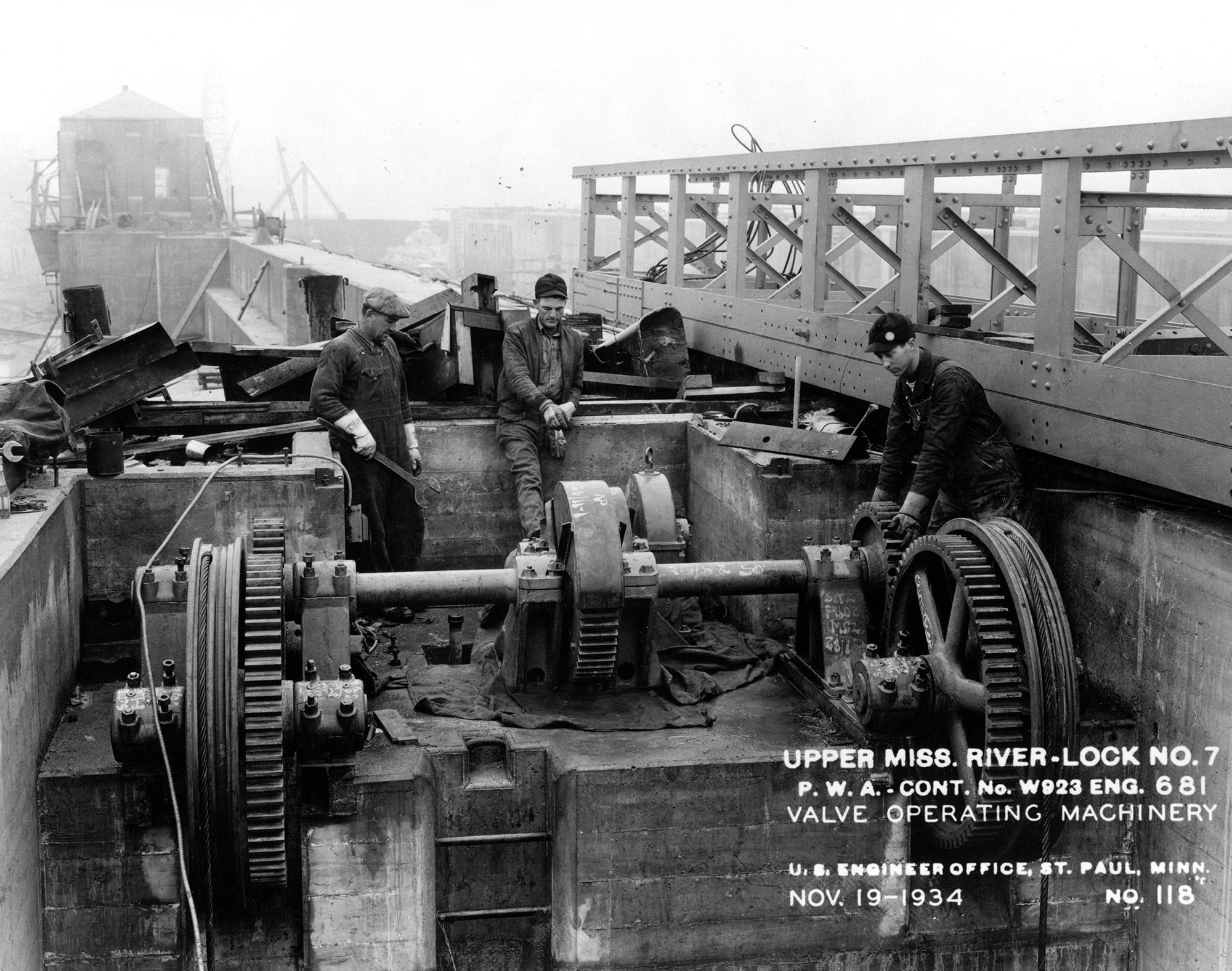

| The valve-operating machinery of Lock No. 7 near La Crescent, Minnesota, a relief project managed by the Corps. 19 Nov. 1934. Office of History |

|

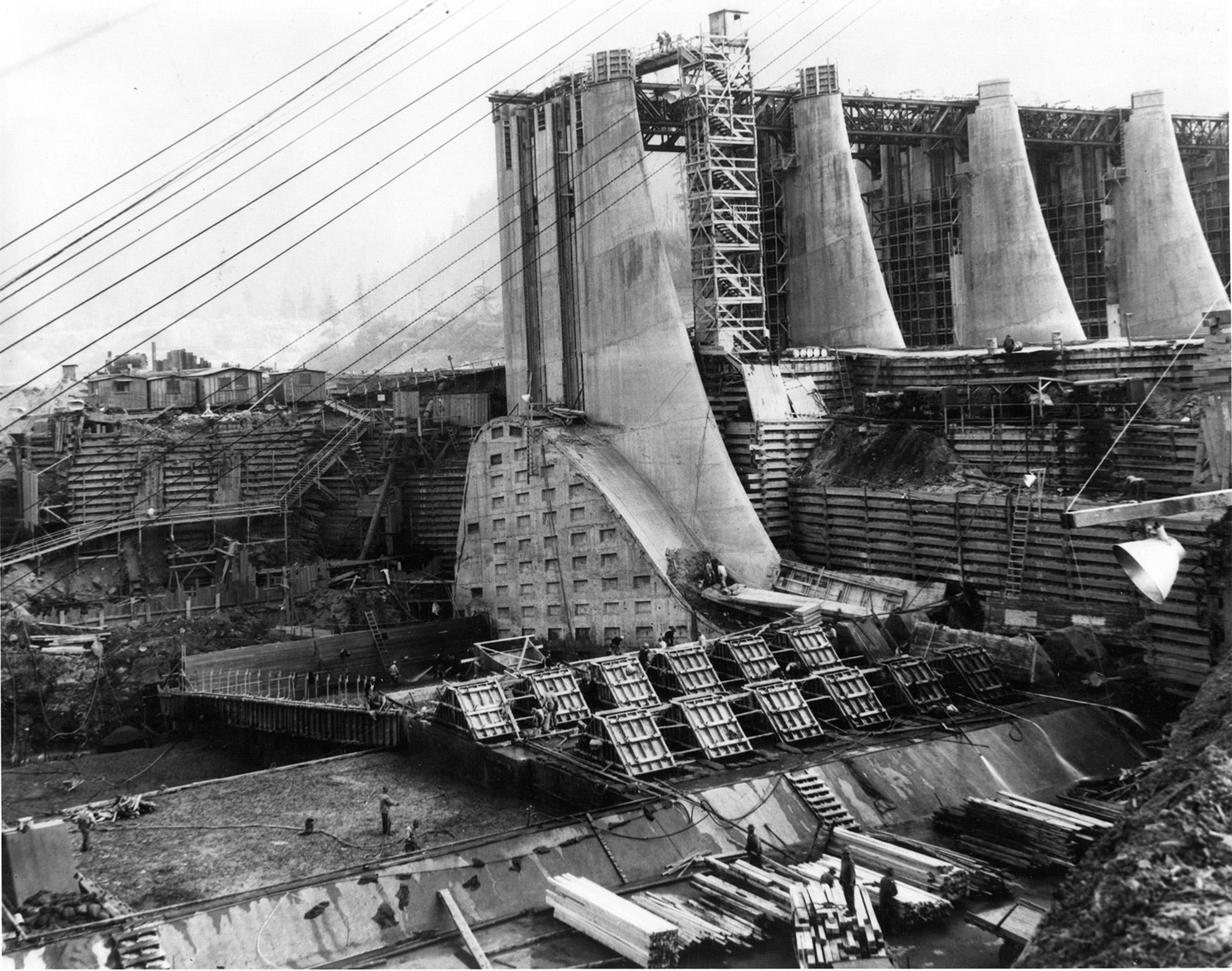

Spillway piers of Bonneville Dam under construction within wooden cofferdams. 24 Oct. 1936. Office of History |

| |

|

|

The destructive floods of the 1920s and 1930s moved Congress to accept federal responsibility for flood control, to declare it a national priority, and in 1936 to assign the task to the Corps of Engineers. At the same time, Army Engineers also shifted to a comprehensive flood-control policy that embraced floodways, spillways, reservoirs, and outlets in addition to levees, and they undertook dozens of flood risk management projects on the lower Mississippi River and around the country. Aside from reducing flood risk, these projects also put tens of thousands of weary Americans to work. Many of these projects evidenced a growing environmental awareness that would culminate decades later in the National Environmental Policy Act of 1970.

During the Depression, changes in both the nature and the volume of the Corps’ workload were accompanied by organizational adjustments. Even then the Corps of Engineers boasted—and maintained—a decentralized and adaptable administrative structure that served it well during the tumultuous period. The chiefs of engineers opened, closed, and rearranged divisions and districts as the workload demanded, sometimes creating offices specifically to manage large relief projects—such as Bonneville (Oregon), Fort Peck (Montana), Tucumcari (New Mexico), and Eastport (Maine) Districts, among others. The Depression also altered the personnel makeup of the Corps of Engineers; the size of its officer corps and civilian workforce steadily increased as Congress and the president assigned more and more projects, both regular and work relief, to the Corps. In addition, given the competency and efficiency of the Army Engineers, the Roosevelt administration called upon select officers to oversee major elements of other New Deal public works programs or agencies.

|

|

|

Men placing the first riprap on the upstream slope of the East Barre Dam,

a flood control project on the Jail Branch River in Vermont.

7 Aug. 1934. Office of History |

|

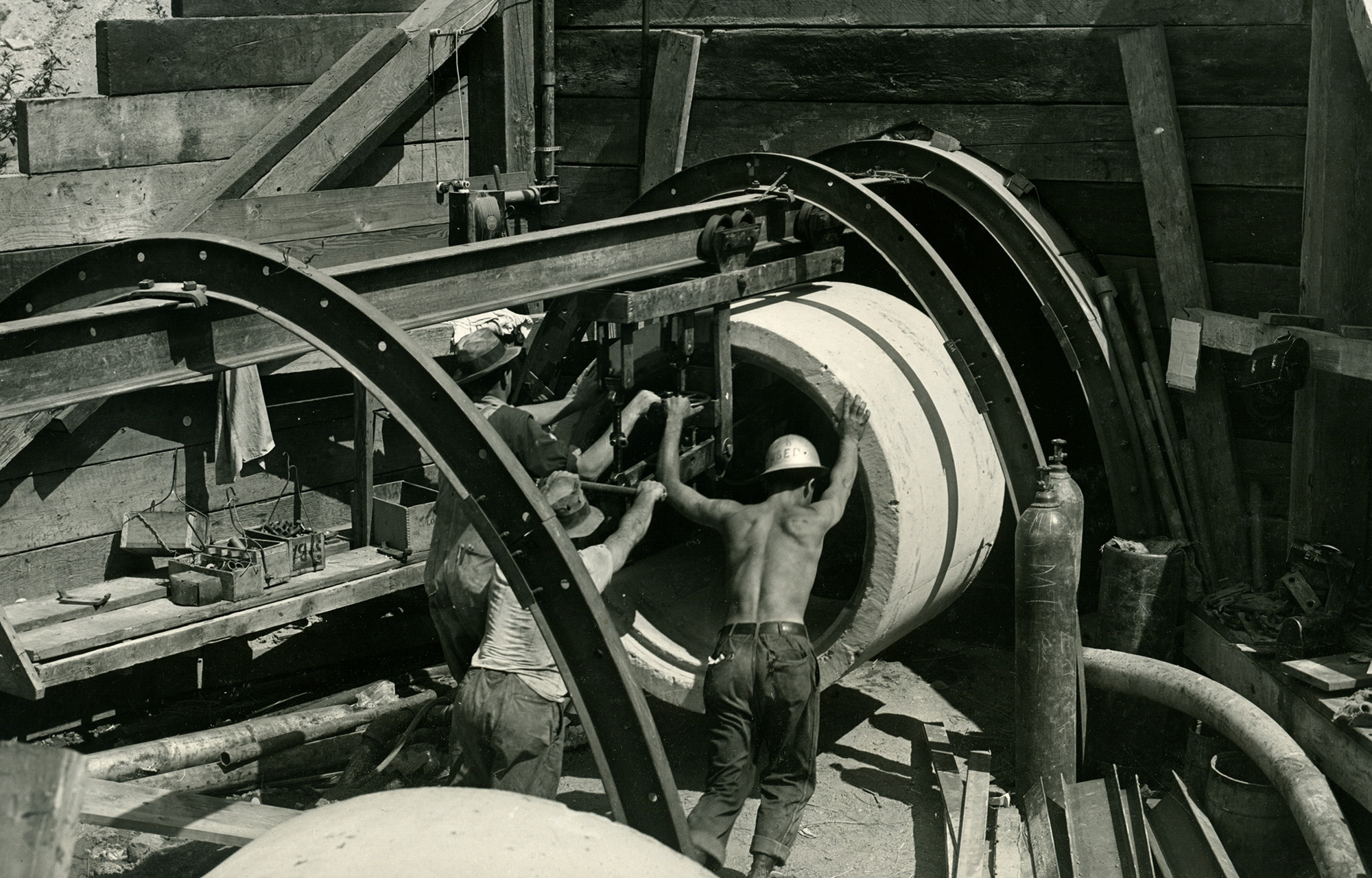

Workers move a 60-inch pipe into position in a relocated sewer tunnel under the Los Angeles River as part of a channel improvement project.

30 Jun. 1939. Office of History |

| |

|

|

Meeting the multifarious demands of its civil works mission during the 1930s enhanced the Corps’ administrative and contracting skills and expanded its knowledge of the latest construction methods. These enhanced capabilities gave the Corps a solid foundation for managing the massive military construction program that served the agency well following U.S. entry into World War II.

Civil Works for the Public Good: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers and the New Deal, 1929-1941, is a newly published book by the Office of History. It chronicles the participation of the Corps and its personnel in the federal response to the economic crisis of the 1930s in the form of a nationwide public works relief program. It is illustrated with dozens of vintage photographs, most of which are available through the USACE Digital Library. The history reveals, again, the remarkable ability of this organization to respond to diverse challenges, to adapt to new circumstances, and to serve this country unfailingly.

|

| The USACE field organization in 1930 after Hoover reorganized the divisions based on river basins. |

***

March 2024. No. 163.