| |

|

| |

Chief of Engineers Maj. Gen. Alexander Mackenzie, ca. 1908. Mackenzie was a skeptic of federal hydropower development. Office of History

|

Today the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is the largest generator of hydropower in the nation, with 75 power-producing dams housing 356 individual generating units. The Corp’s hydropower assets generate more than 70 million megawatt-hours per year of clean renewable energy, enough to power 10 cities the size of Seattle. Surprisingly, when the twentieth century began, the Corps was in the position of opposing any involvement in the new form of power generation. But in the era of the New Deal, only three decades later, it had changed opinion to one of total endorsement. What began for USACE then as a regulatory role in hydropower expanded to include much more. By the mid-twentieth century, the Corps of Engineers had emerged as the largest constructor and operator of federal power generation facilities.

The core mission: navigation

At the beginning of the twentieth century, during the Progressive Era, the Secretary of War’s office became embroiled in a controversy over the development of water projects “for multiple purposes.” Multipurpose planners sought to develop coordinated river basin programs that responded to a wide variety of needs, including navigation, flood control, irrigation, water supply, and a still-new technology—hydroelectric power. The Corps generally opposed the concept, arguing that other purposes should always be subordinated to navigation in federal projects, that multipurpose dams would be difficult to operate, and that greater coordination among agencies involved in these purposes was not needed.

In January 1905 the Chief of Engineers, Brig. Gen. Alexander Mackenzie, summed up the Corps’ traditional views on the federal government’s limited role in improving American waterways. Congress, he said, could legally “exercise control over the navigable waters of the United States … only to the extent necessary to protect, preserve, and improve free navigation.” Mackenzie further maintained that nothing should be permitted to interfere with the central purpose of locks and dams—to facilitate navigation and commerce. All other interests were clearly secondary. These views fit the prevailing judicial interpretation of federal powers under the Constitution’s Commerce Clause going back to the 1824 Supreme Court case of Gibbons v. Ogden and the origins of the Corps’ civil works mission.

.jpg?ver=Ub9nyH7vSPWmYhApI5N_tw%3d%3d) |

|

|

|

Workers placing a stator for a hydroelectric generator at Wilson Dam on the Tennessee River, 1925. Originally designed to provide emergency power for World War I nitrate plants, Wilson was the first federal hydropower project. Office of History, Robinson Collection

|

|

|

During the years following Brigadier General Mackenzie’s pronouncements, attitudes gradually changed. In the early twentieth century, Army engineers became convinced that the escalation in private dam building, largely for hydropower purposes, threatened to jeopardize their prerogatives in navigation work, and they guarded those prerogatives jealously. While the federal government redefined its part in water resources development, the Corps staked out its own territory. The possibility of including hydropower production in water resources projects, as an auxiliary to navigation and later to flood control, benefited from more liberal interpretations of federal authority. Cautiously, with frequent hesitation and some inconsistency, the engineers embraced the new philosophy.

One example of this new philosophy in application was Wilson Dam on the Tennessee River at Muscle Shoals. When the Corps completed it in 1925, it was the first federal hydropower project. When construction had started in 1918, the generators at Wilson Dam were meant to provide plentiful, cheap power for manufacturing munitions for the First World War. While that conflict came to an end that same year, the project was completed and became an early demonstration of the Corps’ capability to build hydropower facilities.

| |

|

| |

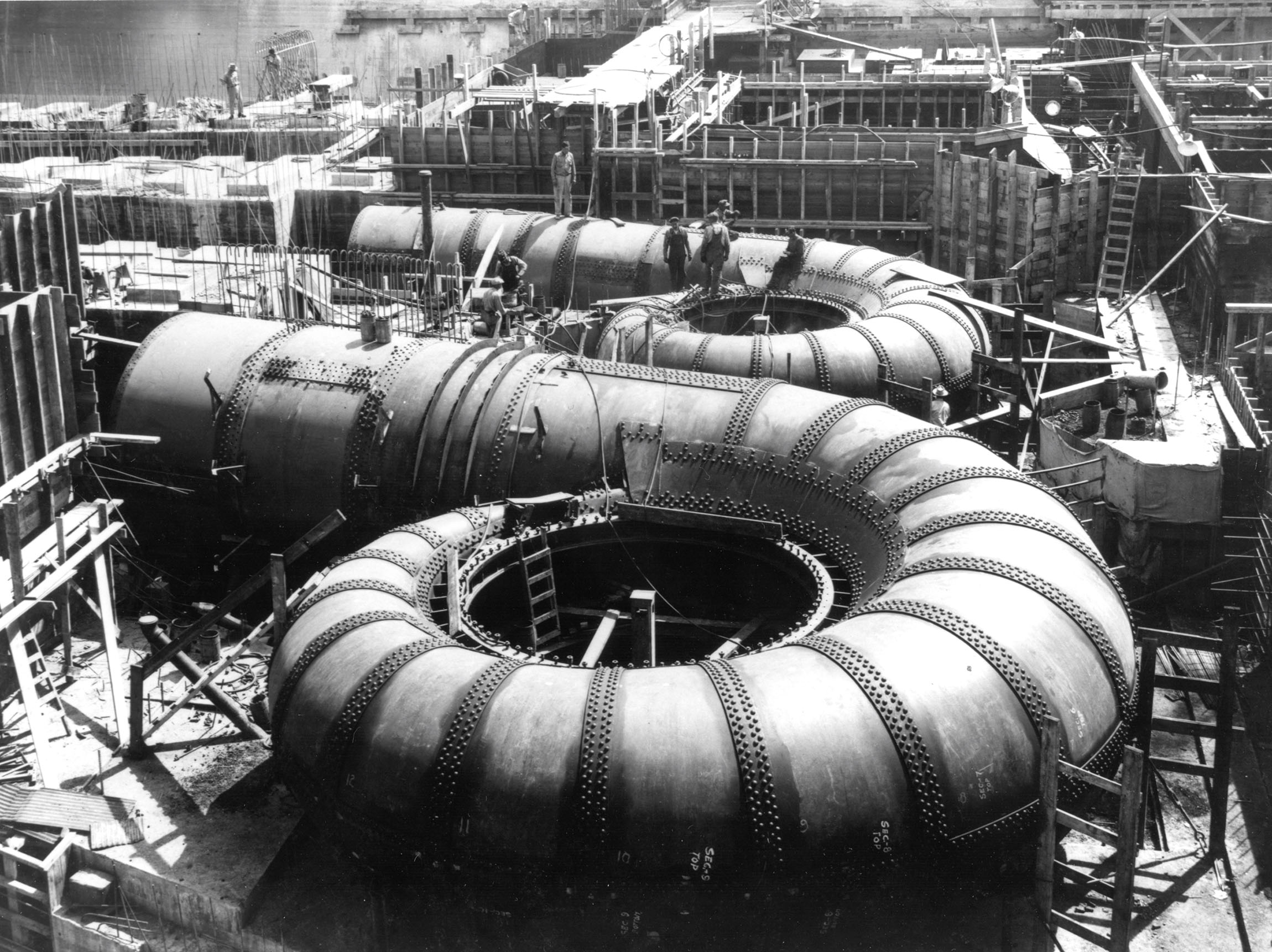

Scroll cases for powerhouse units at Fort Peck Dam, Montana, 1941. The Fort Peck project was both a major work-relief program and a hydroelectric facility.

Office of History

|

308 Reports

In 1925 Congress authorized the Corps to survey the country’s navigable streams to formulate plans for the improvement of navigation and to provide flood control, irrigation, and, conspicuously, “water power.” The surveys and their results came to be called “308 Reports,” named after Congressional Document 308, in which the Corps and the Federal Power Commission had jointly presented to Congress the estimated cost for the surveys. Over the following two decades, the Corps produced and transmitted more than 176 river surveys to Congress under the auspices of the 308 Program. Each individual report provided specific data at the river basin scale, and gave federal, state, and local officials a basis on which they could make decisions about proposed projects. Only 16 of the reports recommended direct federal involvement when originally submitted.

With the onset of the Great Depression in 1929, however, and the economic upheaval it brought, public works projects that were once considered a poor investment for the federal government suddenly began looking more attractive as a means of employment as part of work relief programs. Moreover, many politicians felt that flood control was essential to protect human life, no matter what the economists said. Reflecting the increased Congressional interest, the Corps reassessed a number of projects. Revised surveys concluded that the necessity for “public-work relief” and the suffering caused by recurring floods provided justification for construction of many of the projects. After Congress officially gave the Corps a nationwide flood control mission in 1936, it became a significant aspect of the Corps’ work during the New Deal, and the Corps also gravitated towards new, multipurpose projects that, notably, often included the provision of hydropower.

Hydropower Development

Following a pause during World War II, USACE involvement in hydropower development took off after 1945. Prepared with surveys made under the auspices of the 308 Reports, the Corps had more than twenty multipurpose projects under construction by the mid-1950s. Chief of Engineers Lt. Gen. Lewis A. Pick referred to the development of hydropower as “one of the most important aspects of water resource development.” Further, he argued, “proper provisions for hydroelectric power development are an essential part of comprehensive planning for conservation and use of our river basins for the greatest public good.”

.jpg?ver=JxfZGUlA5wF458G1qeJGVw%3d%3d) |

|

|

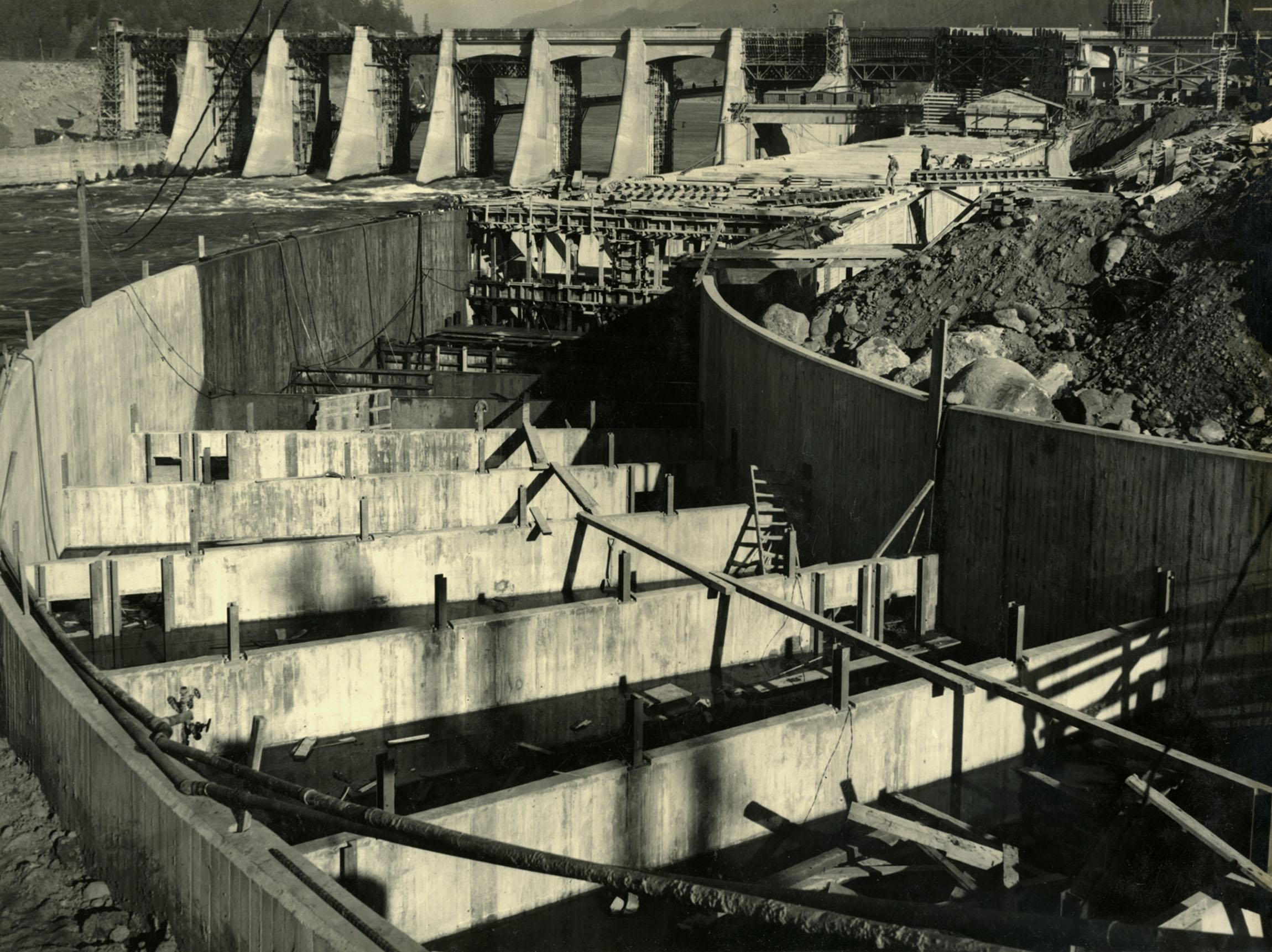

John Day Dam on the Columbia River

under construction in 1965.

University of Idaho Library Digital Collections |

|

Bonneville Power and Navigation Dam, a New-Deal era project under the Public Works Administration and built by the Corps of Engineers. Concrete fish ladders under construction in the foreground, 1936. Office of History

|

| |

|

|

The largest hydropower dams built by the Corps are on the Columbia and Snake Rivers. The biggest of these are John Day and Chief Joseph Dams, both on the Columbia and each with a generating capacity of around 2,100 megawatts at their usual power. By 1975 the energy produced by Corps hydroelectric facilities was 27 percent of the total hydroelectric power production in the United States and 4.4 percent of the electrical energy output from all sources. These dams provided cheap, reliable electricity, which fueled economic growth and industrial development in regions such as the Pacific Northwest. Hydropower became the backbone of that area's energy system, supplying nearly half of its annual electricity generation.

In retrospect, however, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers did not fully anticipate the ecological consequences of the era of large dams that followed World War II, especially on migratory fish species such as salmon. For example, although features such as fish ladders were included in the original construction of early New Deal-era dams like Bonneville to mitigate impacts on salmon migration, these measures often fell short of addressing the broader ecological disruptions caused by dams. Issues such as habitat loss, altered river dynamics, and sediment transport were not fully understood or prioritized in the planning and design phases, leaving a complex legacy for a twentieth century revolution in how the Corps of Engineers saw its role in water resources development.

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

250th Anniversary

April 2025. No. 05. |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|