| |

|

| |

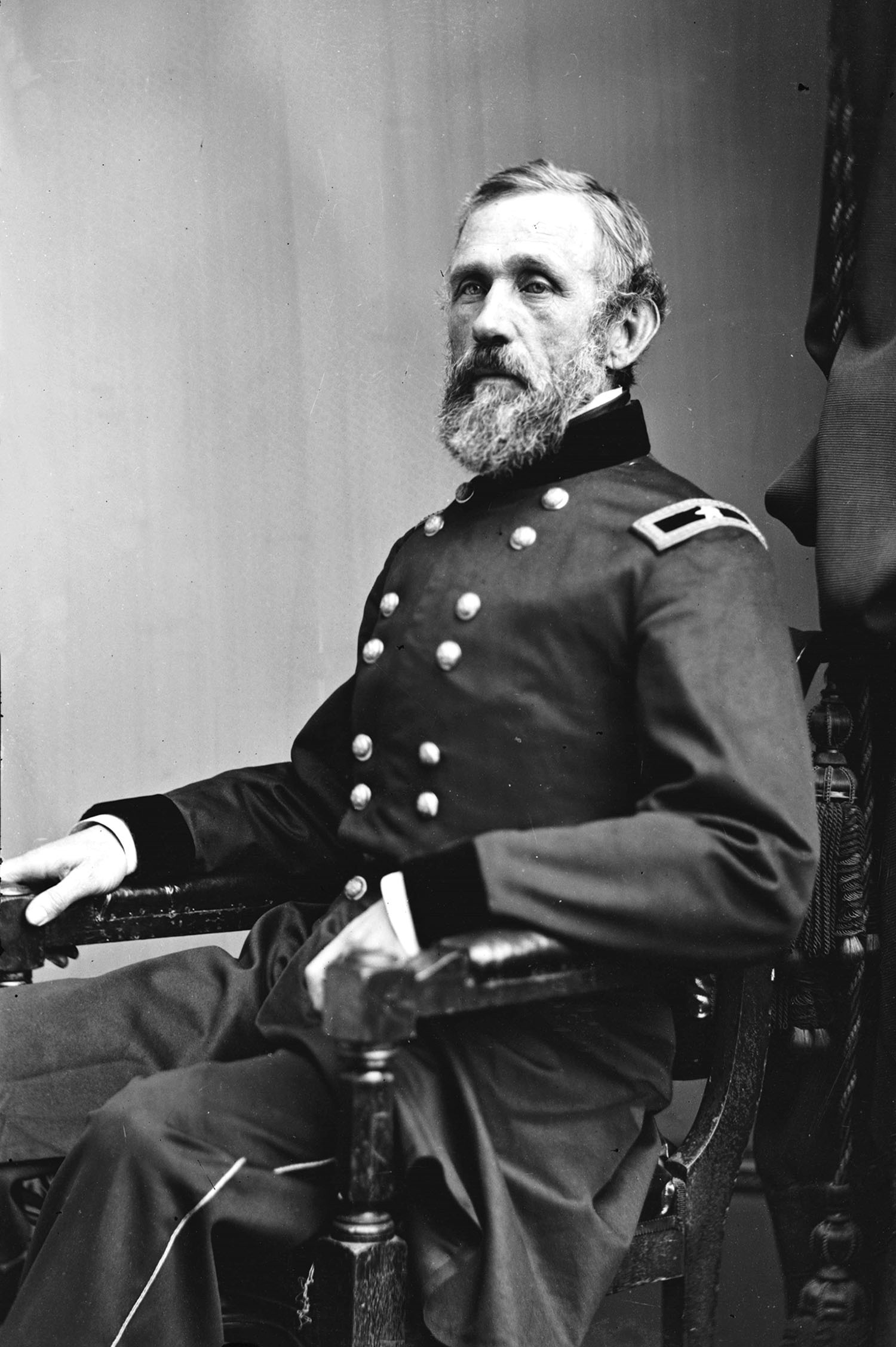

John Gross Barnard (as a Brigadier General, ca. 1865). As Chief Engineer of the Army of the Potomac, 1861–62, Barnard’s most important assignment was to construct the defenses of Washington. Library of Congress

|

| |

|

| |

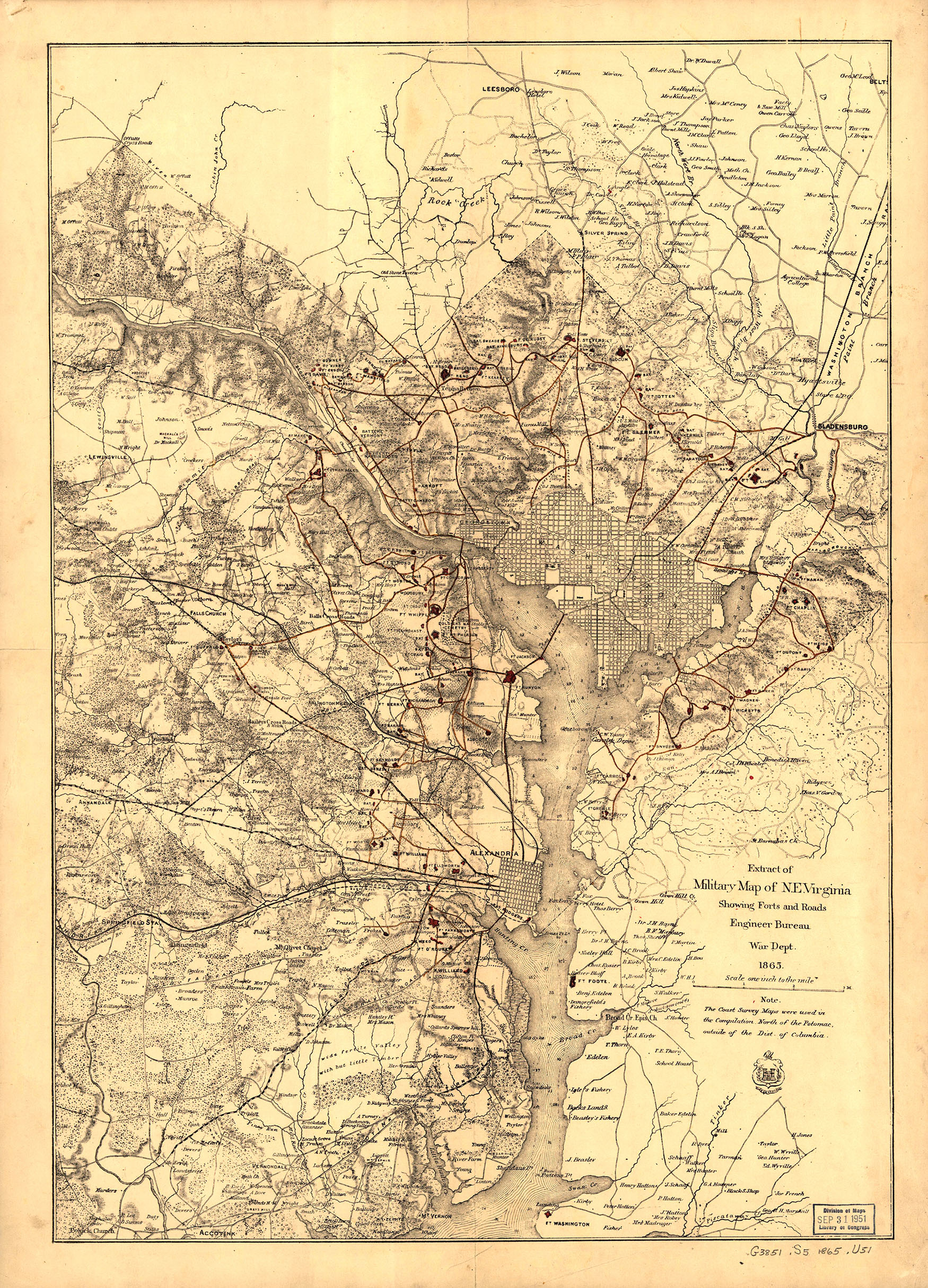

Map of fortifications and military roads in the Washington area, 1865. Office of History |

If there was one thing that most occupied the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers during the American Civil War, it was defending the capital of the Union. Washington, D.C., was located only a hundred miles from the Confederate capital of Richmond and was sandwiched between one state in rebellion and another with strong Southern sympathies. As U.S. Army officers took sides in the conflict and assumed volunteer commands with their state forces, there were only thirty regular commissioned engineers that remained with the Corps through the war. Half of them were on duty in the capital to build its defenses. Eventually those defenses would surround Washington and make it one of the most heavily fortified cities in the world.

After Virginia officially seceded from the Union on May 23, 1861, federal troops crossed the river and occupied Arlington Heights. They then marched southeast to occupy Alexandria. The troops erected earthworks and a half dozen forts to secure the army's advanced position in northern Virginia. These early earthworks generally consisted of six-foot-high embankments fronted by twelve-foot-wide and eight-foot-deep trenches with openings at the top for artillery and elevated platforms for infantry fire. Initially, the defenses were not strong or interconnected enough to withstand large frontal assaults, to prevent small raiding parties from infiltrating the city, or to endure long-term sieges. Instead, they created a series of defensive works to support and protect Union armies in case of defeat in the field. In the event of a rout, troops could fall back to the line and make the passage of an enemy army extremely difficult, as happened in July 1861 after the first battle of Bull Run.

Shortly after that defeat thirty miles from Washington, President Abraham Lincoln appointed former Army Engineer Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan as the new commander of the Army of the Potomac. McClelland recognized the importance of having strong defenses for the capital city and appointed Maj. John Gross Barnard as the Chief Engineer of his army. Together they went to work strengthening the city’s defenses while federal forces prepared for their next offensive.

Over five months from August to December 1861, Barnard oversaw the first expansion of the jagged line into a defensive system that could withstand a full-frontal assault by adding a series of twelve-foot chevaux de frise, anti-cavalry barriers made of sharp pointed timbers, and smaller fortified positions with connecting trenches. Barnard increased the number of fortifications on the Virginia side to ensure each was within cannon shot of one another and expanded the system into Maryland to protect some of the major approaches to the capital from the north and west. By the start of 1862, the defenses of Washington spanned roughly 35 miles and comprised 37 forts and 443 artillery pieces.

Confederate campaigns into Maryland that summer and fall convinced Congress to fund a second expansion of fortifications that would eventually ring the capital city and dramatically change its landscape. According to Barnard, having evolved from “a few isolated works covering bridges or commanding a few especially important points,” the defenses of Washington by 1864 were truly a “system of fortification by which every prominent point, at intervals of 800 to 1,000 yards, was occupied by an enclosed field-fort, every important approach or depression of ground, unseen from the forts, swept by a battery for field guns, and the whole connected by rifle trenches . . . furnishing emplacement for two ranks of men and affording covered communication along the line.”[1] Furthermore, the engineers had built roads wherever necessary to move troops and artillery from barracks in the city to anywhere on the periphery, all completely out of view of an approaching enemy.

By April 1865 the Corps had overseen the expenditure of $1.4 million to construct 20 miles of rifle pits and 30 miles of military roads serving more than fourteen-hundred gun emplacements in sixty-eight forts and ninety-three batteries completely surrounding Washington. The completed network of fortifications reduced the numbers of soldiers required to defend the city while extending greater freedom to the Union armies to attack deep into Confederate territory.

After the war, the military roads connecting the forts to the city played a significant role in changing settlement patterns in rural parts of the District of Columbia, Virginia, and Maryland. Some of these roads continued for many years—into the modern era—to serve as important transportation routes, encouraging further development and settlement in the area.

Today, many of the remaining fort locations have become public parks and the military roads, suburban neighborhoods. Arguably the greatest national landmark that has endured the passage of time is Arlington National Cemetery. Robert E. Lee’s 1,100-acre Arlington plantation, from which the heights it sat atop were named, was one of the first tracts occupied by federal forces in 1861. Over the course of the war, engineers built two large fortifications on the plantation—Forts Whipple and McPherson—along with the smaller Fort Cass. When Montgomery Meigs, Quartermaster General and former colleague of Lee, was tasked with finding a new suitable place to bury federal troops who had perished in D.C. hospitals and on northern Virginia battlefields, he too looked to Arlington Heights. Not only did burying Union dead around their garden deprive the Lees of their ancestral lands and prevent them from ever returning, the new cemetery backed up to heavily-guarded defensive positions, meaning there was ample Army labor to convert the plantation into a national cemetery. After the war, the cemetery was expanded to include the area once occupied by Fort McPherson, now Section 11, which added 100 acres for burials, and Fort Whipple is today Joint-Base Myer-Henderson Hall.

[1] John G. Barnard, A Report on the Defenses of Washington, to the Chief of Engineers, U. S. Army, Corps of Engineers, Corps of Engineers Professional Paper No. 20 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1871), 32-33.

|

|

|

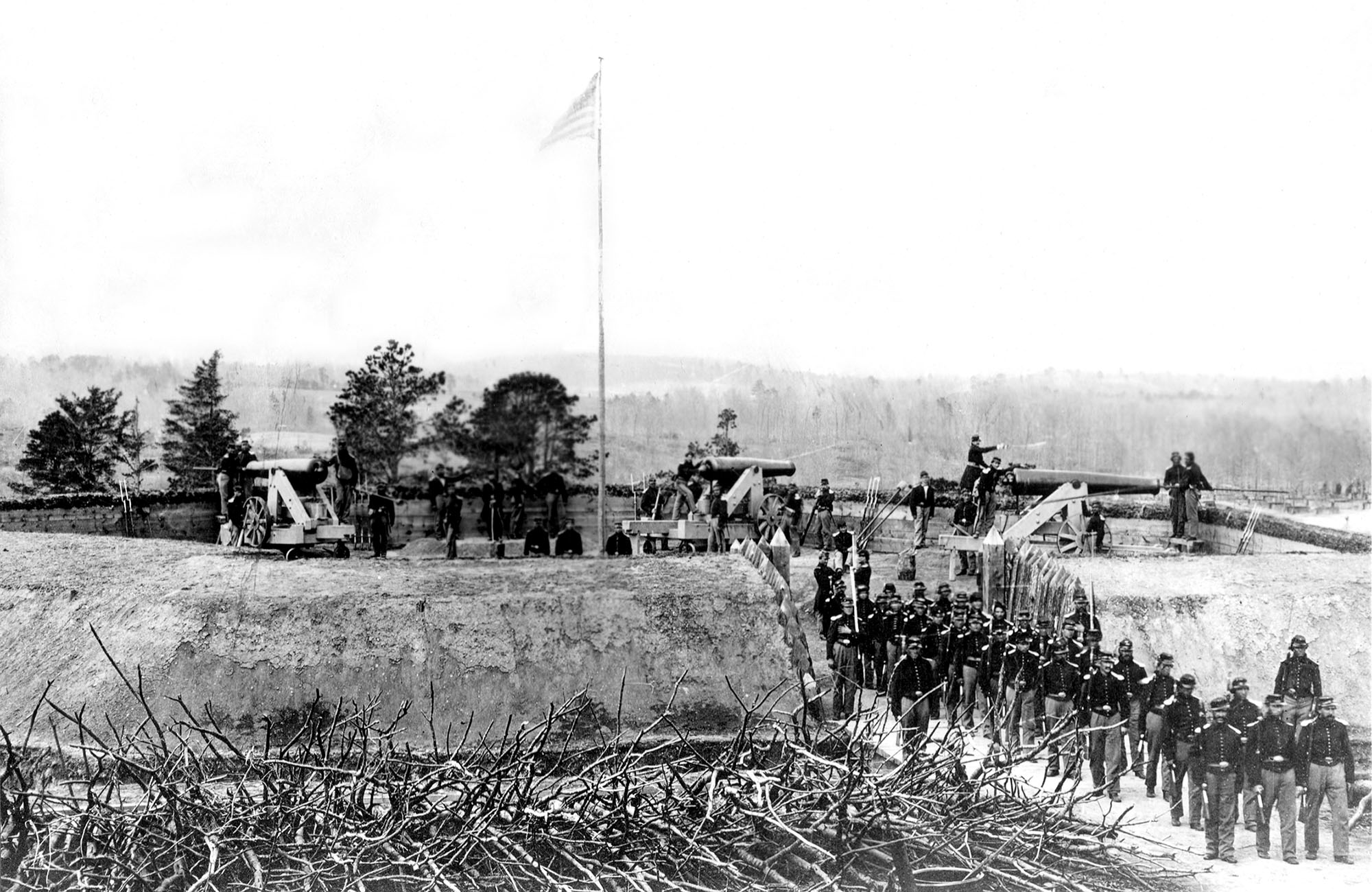

| Fort Stevens in 1864. At the time, Seventh Street Pike, the main road north into and out of the city, ran next to the fort. On July 11, Fort Stevens came under attack by Confederate forces under Jubal Early, who approached from Maryland to the north. President Lincoln insisted on visiting the defenses during the attack, which was quickly repelled. National Archives |

|

Fort Whipple, Arlington, Virginia, June 1865. Fort Whipple became part of Arlington National Cemetery after the war. Library of Congress

|

| |

|

|

2010.jpg?ver=2kwkwMsVD4X6_ly5tli6nw%3d%3d) |

|

Historic fortifications of Washington with their locations on a contemporary regional map. The National Park Service manages 19 sites today that were part of the original defensive system. Park Service Map, 2010, via Library of Congress

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

250th Anniversary

June 2025. No. 09. |

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|